马宏杰

1963年出生于河南省洛阳市,回族。

1987年 开始自学新闻写作、散文写作。

1994年 武汉大学新闻摄影专业毕业。

1994年 任《河南经济日报》摄影记者。

1997年 任《河南法制报》摄影记者。

1998年 任《焦点杂志》特约记者。

2001年 任《百姓信报》摄影记者。

2001年9月, 参加首届平遥国际摄影大师班培训。

2003年 任《豫情时报》摄影记者。

2004年8月, 考察长江源头并进行为期一个月的拍摄。

2004年至今 任《中国国家地理》杂志社图片编辑。

2005年5月, 独自对青藏铁路进行一个月的考察拍摄。

2006年10月,进入可可西里无人区,进行为期40天的考察拍摄。

2007年1月, 在河南省、陕西省考察拍摄“中华姓氏起源”的专题。

2008年5月, 应The North Face邀请,前往美国约塞米蒂国家公园(Yosemite National Park) 拍摄。

2008年8月, 沿着黑龙江进入俄罗斯,最后到达入海口进行考察拍摄。

2008年10月,前往伊朗访问拍摄。

2009年4月, 前往马来西亚考察拍摄。

2009年4月, 前往越南、印度尼西亚拍摄那里的中国人。

2009年5月, 进入中国南海海域到达曾母暗沙、北康暗沙、琼台礁、弹丸礁等南海诸岛考察。

2010年5月, 前往中国西沙群岛、中沙群岛进行考察拍摄。

2010年6月, 前往中国南沙群岛中国驻守的岛礁上进行考察拍摄。

2010年10月,前往俄罗斯远东地区、贝加尔湖等地考查拍摄。

2010年11月,前往美国拉斯维加斯、盐湖城等地拍摄。

2010年11月,前往秘鲁马丘比丘古城、印加古盐田拍摄。

2010年12月,第二次前往中国西沙群岛考察拍摄。

2011年10月,组织中国GEO组织在土耳其的展览策划。

2011年11月,受德中友好协会邀请赴德国考察德中文化周活动项目。

2012年5月, 第三次次前往中国西沙群岛考察拍摄。

2012年8月, 在德国波茨坦策展中国摄影师《中国景象》十人展。

2013年5月, 第四次前往中国西沙群岛考察,航拍西沙群岛所有的礁。

擅长拍摄社会纪实类图片,主要作品有《唐三彩》、《西部招妻》、《采石场》、《割漆人》、《采药人》、《耍猴人》、《年画人家》、《黄河上的人家》、《中国人的家当》、《中国1988~2008》、《中国南海》等20多组专题图片。

获奖:

1995年2月 专题摄影报道《幸福井前的欢笑》获得河南省好新闻二等奖。

1999年10月,摄影作品《赶场》获文化部群星奖铜奖。

2000年1月, 摄影作品获千禧年香港中国旅游摄影比赛金奖。

展览:

2012年7月,作品参加陕西《民间》摄影展。

2011年3月,《家当》在英国SEASAME画廊展出。

2009年7月,《家当》摄影作品参加意大利国际摄影节。

2009年1月-2010年1月,《家当》摄影作品参加在北欧丹麦、挪威“弥散成像”展览。

2007年12月,作品《家当》,在北京798“百年印象”摄影画廊展出。

2003年9月, 在平遥国际摄影节上举办河南十三人《乡土中原》摄影联展。

2002年9月, 摄影作品参加中国平遥国际摄影节大展。

出版:

2015年4月,出版《中国人的家当》画册。

2015年1月,出版《最后的耍猴人》一书。

2014年8月,前往东沙群岛考查拍摄。

2014年5月,出版《西部招妻》一书。

收藏:

2011年5月,出版《民本》画册。

2008年9月, 作品《荡秋千》被广东美术馆收藏。

2008年8月, 摄影作品参加中国华辰影像作品拍卖。

2004年4月, 四幅摄影作品被河南博物院收藏。

2003年9月, 四幅摄影作品被法国EGMO画廊收购。

2003年8月, 六幅摄影作品被广东美术馆收藏。

Ma Hongjie

Muslin,born in Luoyang,Henan

Specialized in social documentary photography,main works include: "Tri colored glazed pottery of the Tang Dynasty", "Western Recruit Wife", "Quarry", Cut The Painting "," Herbs "," Monkey Man "," Pictures of People "," The Yellow River People ", The Belongings Of The Chinese People," China From 1988 To 2008 "," South China Sea "

Awards

“Laughing at the Happy Well”, second award of the Henan Good News

“Fair”,bronze award of the Cultural Department

Golden award of the Millennium Hong Kong-China Tour Photo Competition

Exhibitions

Folk Exhibition,Shanxi,China

“Home Belongings”,SEASAME Gallery,Great Britain

“Home Belongings”,International Photo Festival,Italy

“Home Belongings”,Mass Imaging,Denmark & Norway

“Home Belongings”,Impression of Hundred Years Gallery,Beijing

Joint Exhibition“Local Central Plains”,Pingyao International Photo Festival Pingyao International Photo Festival

Publications

“Chinese Home Belongings”

“the Last Monkey Player”

Took photos on East Sand Islands

“Marrying Wives in western China”

Collections

Published “Citizenism”

“Swinging”,collected by Guangdong Art Museum

Participated in the China Huachen Photo Works Auction

Four Works Collected by Henan Museum

Four Works Collected by EGMO Gallery(France)

Six Works Collected by Guangdong Art Museum

中国人的家当

马宏杰1963年在河南省洛阳市的一个工薪家庭中出生,这似乎意味着他也将会跟随父辈的脚步。他的父母是一家国有玻璃厂的工人。在那个年代,这是一份相当稳定的工作,收入体面,住在工人集体宿舍,孩子能够就读厂子弟学校。生活尽管不宽裕,但也能满足全家人的温饱需求。马宏杰中学毕业后也在厂里工作了一段时间。工人的经历在他后来的创作生涯中影响着他的摄影视角,使得他尤其敏锐地看到老百姓日常生活的兴衰变迁和艰辛。

与很多中国人一样,马宏杰童年的大部分时光是在贫穷的农村跟祖父母和家中的兄弟姐妹们一起度过的。从孩提时起,他就有强烈的社会正义感。他的祖父驮了一辈子粮食,背部严重扭伤,腰弯成九十度,再也站不直了。马宏杰至今还记得自己上小学的时候,因为看到大伯不肯帮祖父背一袋沉重的玉米而气愤。他记得当时的自己多么渴望能为祖父母做点什么,为他们的生活减少一些艰辛。

像大部分当地人一样,马宏杰的祖父母把家安在山坡上的窑洞里。从土墙中挖出一个不大的开孔做窗,再挖出一扇小门,好让那一点点微弱的自然光透过窗纸照进家里。马宏杰特别想从玻璃厂里弄一块玻璃回来,给祖父母置一扇像样的窗,让屋里更亮堂些。善良的祖母严厉训斥了他,说即便家里的窗子永远安不上玻璃也比偷东西强。祖母除了强调道德规范,也特别向马宏杰灌输受教育的重要性。他就学期间,祖父母在一年之中相继去世,他偷玻璃的计划始终没有得以实现。尽管祖父母已经不在,农村劳动人民生活的艰辛和尊严却在他心中留下了深深的烙印,其精神至今仍渗透在他的作品中。

马宏杰的父亲曾梦想去念大学,也考上了,却因为祖父患病而不得不放弃这个梦想。为了照顾生病的父亲,他必须工作,结婚后有了三个孩子,可梦想却从未在心中消失。马宏杰回忆起那满是冲突、缺少温暖的家庭生活,回忆起儿时的自己多么渴望自立,他知道未来需要自己去创造,去追求。

那份追求便是摄影。通过镜头,马宏杰找到了一种观察社会的全新视角,找到了一种在他看来最有意义的对世界的题献。他1982年开始用朋友的相机自学摄影,学会了冲洗胶卷、印照片,技术越来越好,后来已经能靠为别人冲印彩色照片挣钱。两年后,他娶了一位中学同学为妻,换到拖拉机厂工作,再没有更多的时间投身摄影。他与妻子有了一个儿子,夫妻两人艰难地养家糊口。

在贫困时期,马宏杰不得不变卖自己的相机。但他并没有长时间脱离摄影,放弃不是他的风格。儿子三岁那年,他开始研习摄影理论,借来一台相机,开始向不同的平面媒体投寄摄影作品,想碰碰运气。很快,他的作品收到了相当热烈的反响。

在获得不少摄影奖之后,马宏杰终于有了信心于1994年向一家报社递交了工作申请,从工人变成了摄影记者。在1997年的早期国有企业改革中,这家报社停业了,而他也必须重新寻找生计。2004年,他开始就职于《中国国家地理》杂志,他的事业上了一个新的台阶。接下来的几年中,摄影记者的工作令他直面平常老百姓生活的种种艰辛,重新唤起了他对祖父艰难生活的记忆。

后来的十年里,马宏杰因为工作任务走遍全国各地,拍下数不清的照片。中国文化的丰饶以及中国社会和经济的巨大变革给他留下了深刻印象,叫他惊诧,他开始自发地记录中国人当下不断改变的生活状况。

他的第一本书《民本》(2010),其中的黑白照片捕捉了中国人在日常生活中的微妙脸庞。马宏杰的创作以起初的纪实性作品作为开端,逐渐转变为现在的摆拍。他这一新的创作阶段在《中国人的家当》里有最为集中的体现。

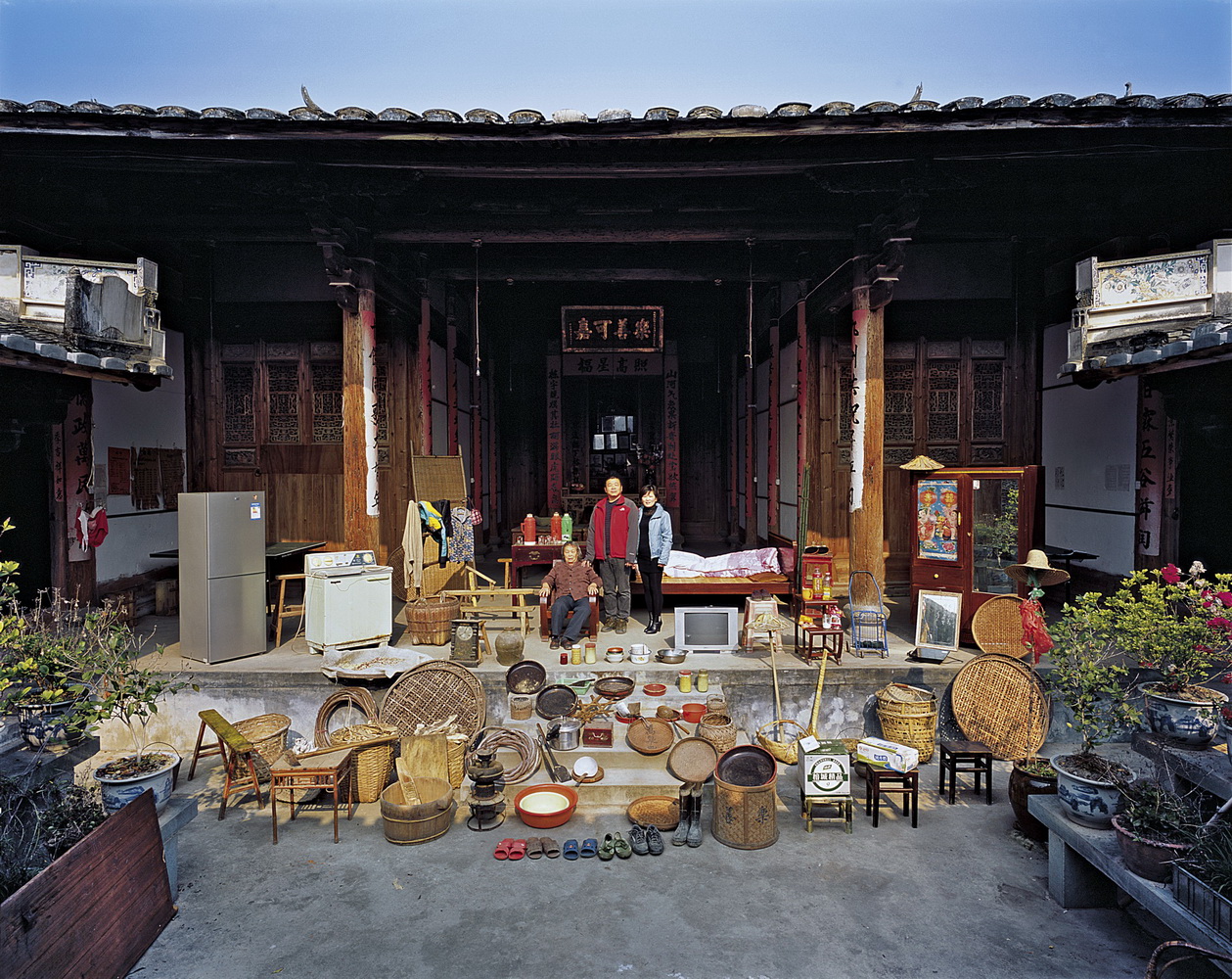

《中国人的家当》是一份敏锐的证书,包含了对都市化进程中的当代中国大环境多种多样的表达。它反映出物质文化怎样通过个人物品体现,这些个人物品中包含了人的故事,有人的生活和命运,喜悦和心酸,以及他们不断的失败和不懈的梦想。

在这一系列作品里,来自不同社会背景的家庭在于自家门口搭建的布景中,跟从自己家中搬出的物品一起摆造型,面对相机镜头。照片中,有男人和女人,男孩和女孩,婴儿和祖父母,年轻人和家长;有汉族人、哈萨克族人、回族人、黎族人和其他少数民族。他们中有的贫穷,是吃苦耐劳、心地善良的工人阶级,省吃俭用,竭力维持最基本的生计,也有小资新贵和富裕的农民。他们来自社会的各个阶层和角落。

他们的家也默默地参与着其中的故事,有命运的改变,有现代化,也有那些不断被拆毁的当地特有的传统建筑。在照片中你能看到用传统工艺烧制而成的陶土瓦和歇山顶彩绘斗拱、坚固的茅草屋顶,和用泥土和稻草搅和做成的砖做的泥墙,还有竹墙、石墙、红砖和水泥钢筋,以及鞣制的动物皮毛盖成的蒙古毡房,以及房屋主人自行设计的现代化房屋。

他们所拥有的物品也同房屋一样,反映着其生活状态和经济条件。其中有精美高级的物品,古董家具、水墨画、古色古香的珍奇摆件,也有极其平常的日常用品。有鸡和猪,驴和马,绵羊和山羊,还有机械工具。从农场到厨房,从田野到工厂,从渔网到晾晒干货的篓子,我们目睹着人们如何在一个剧变中的世界谋求生计。

中国的自然景观在这本作品集中也有它的一席之地,从新疆的吐鲁番盆地,到海南的白沙滩,从江南的水道,到河南的乡村,从一片片向日葵,到广受欢迎的主食玉米,从近乎荒芜的黄土地,到无边蔓延的芳草地,从竹林到落叶树木,从枫树到橡树,我们看到色彩的丰富和横跨中国土地的农耕收获,同时也看到了贫穷、干旱、土地侵蚀和环境恶化。

马宏杰的镜头给予了我们看中国的视角,既深入又宽泛,既客观又深情。翻阅此册,辽阔的、拥有多样性的中国便展现在你眼前,由此证明关于其单调统一的说法之伪,使我们重新审视对这个正在经历巨大历史性变革的国家的本质的假设。

如果这一幅幅画面传达了某种信息,那必定是这样的中国的故事:既浪漫又悲剧,既讽刺又幽默。这故事中的人们既坚韧又认命,既谨慎又野心勃勃,既谦逊又平易,既骄傲又不屈。更重要的是,这些汇合的画面告诉我们,中国的故事是未完成的故事,前方的路于我们是未卜的。这已不再是充斥着虚浮政府宣传手册、旅游指南和满是正面和积极的电视剧的中国。这些画面暗示我们,中国的故事是多样的,是未完成的,多种流派、声音和语言并存,共同讲述自己的故事。这里有数不清的主角,他们既非英雄也非恶霸,不过是不折不扣的普通人。

关于马洪杰的摄影作品《中国人的家当》

王春辰 博士

中国社会进入现代化进程后,社会肌体的变化加速,在某些情况下,甚至可以说变得面目全非。这样的环境为艺术创作提供了巨大的机会,也带来了巨大的挑战,它要求当下的艺术不单单在形式上跟进,更重要的是艺术家应该对社会场域变迁有深刻的心理体验。

《中国人的家当》系列影像作品立足于这样的时代转换,去捕捉我们生活中的物品,以物的形态去透射寄寓其中的人的内在属性。这样,《中国人的家当 》系列作品就成为检视中国生活情境的视觉图景。它们不仅是解读当下中国社会生活的图像文本,也昭示了影像作为艺术所具有的特殊价值和功能。

影像作为艺术不是被动地记录现实,而要体现出艺术家积极介入现实的主体意识。《中国人的家当》这组作品充分显示了影像艺术的这种特殊功能。为拍摄作品, 摄影师走访了中国的许多地区,有意识地去选择那些最有代表性、最有中国当下生活特征的场景。

《中国人的家当》构成的图景向我们揭示了当下中国社会生活状态的内部结构,将原生态家庭生活呈现出来,以物的形式展示出中国当代环境中的生活哲学。在这种主观寻找中国生态的过程中,艺术家建构起现实与虚构之间的关系:真实的内部空间被虚拟地呈现在外部空间中,将中国家庭的境遇展现出来,直接穿透观众的视觉目光。这看似悖论的场景实际上是中国历史大转型中被遮蔽了的东西。如果不是艺术家用直接的方式呈现出如此明确的家当图景,我们会对中国人家庭中的器物组织视而不见,即便见到也不思考,这是艺术家巧用影像艺术强力介入我们的知觉的结果。《中国人的家当》的每一个组成部分都是中国当代社会的生活信仰与生存状况的见证,它们见证了中国现代化进程中生活方式的变与不变。在现实与想象的疏离空间中,《中国人的家当》以视觉启示的方式发现了我们置身其中的生活逻辑,从而确证了中国在全球大变局中的具体在场。

The Family Belongings of Chinese People

Preface

An Unfinished Chinese Story in Ma Hongjie’s Photography

Born in 1963 in Luoyang, Henan Province, from a working class

Family, Ma Hongjie seemed would follow the footsteps of his parents and grandparents. Both of his parents worked at a state-owned glass factory, which was a quite steady job at the time with decent pay, arranged apartments, and schools for their kids. Although it didn’t ensure an abundant life, it was enough to meet the family's modest needs. When he graduated from middle school, Hongjie joined his parents at the factory. The experience of working at a factory later has an influence on his imagery, vision, and gave him the sensitivity to observations of family vicissitudes and the people's struggle in their life.

Like many people in China, during Ma’s childhood, he spent most of time in the impoverished suburban countryside with his grandparents and siblings. Since he was a child, he had had a strong sense of justice. At the time, his grandfather had hurt his back, so every time he needed to carry packages of grain, he had to wrench the back into a 90-degree angle to be able to stand upright. Ma still remembered that he felt angry because his paternal uncle refused to help his grandfather with carrying a heavy bag of corns. He always wanted to help even as a little boy, to help with anything that somehow making the grandparents' life easier.

Same as many local people in the village, Ma Hongjie's grandparents built their home in a hillside cave. In order to see the natural light, they had to carve out a tiny door and a small hole for the window. Hongjie wanted to steal a piece of real glass from the factory to cover the window space. After hearing about his plan, his grandmother gave him a lecture about “Never to steal, even life is hard”. Other than insisting her strict moral upbringing to Hongjie, grandmother told him that she believes in the importance of education. Years later, both grandparents died when Hongjie was still in school. However, the influence of his grandparents and the experience of living in rural countryside are revealed in his photographic work.

Ma Hongjie's father had dreamed of studying in college and he did pass the test but eventually had to give up because of his father had gotten tuberculosis. Ma’s father had to go to work to take care of his ailing father, had to get married. The dream was still in his heart, even later had three children.

Hongjie recalls his childhood life with family conflicts and hard time, he was long in finding happiness in his own life and earning a bright future by himself.

The pursuit later was photography. Through the language of lens, Ma

Hongjie discovered a whole new vector for investigating society and inscribing himself into the world in a way that made it meaningful for him. In 1982, he discovered the power of the camera and began to teach himself to take pictures with the camera of a friend. He learned to develop film and print his own photographs and became good enough to start making money developing color photographs of other people. After two years, he got married to a woman with whom he had gone to middle school, and went to work in a tractor factory, leaving him no time to do photography. They had a son, and struggled to make ends meet in the changing economy. During these economic hard times, Hongjie had to sell his camera. But he could not keep away from photography for long and giving up was not his way. When his son was three, he started reading up on photographic theory and borrowed a camera once again so he could begin to submit his pictures to various print media to see what could come of it and discovered that his work was enthusiastically received.

After his photographs won several prizes from various magazines, in 1994, Ma Hongjie worked in a newspaper company and made the unlikely transition from a worker to a photojournalist. In 1997, however, during an early wave of enterprise reform, his newspaper was shut down and he had to seek another position. Then in 2004 he began to work for Chinese National Geography, taking his career to a whole new level. Over the next few years, his work as a photojournalist exposed him to the struggles of ordinary people and rekindled his memories of the bitterness of his grandfather's life.

Over the next decade, Ma Hongjie traveled the country on assignment taking countless pictures. The cultural richness of the Chinese people, and the enormous changes taking place in society and the economy impressed him, and he began to self-consciously document the changing conditions of their lives.

His first book, Grassroots (2010), is a tome of black and white photographs that captures the many subtle faces of everyday life in China. Ma Hongjie's practice has now evolved from its documentary roots and has crossed the boundary into contemporary, staged photography. The strongest works from this new practice of his come together in this volume, The Family Belongings of Chinese People.

The Family Belongings of Chinese People are a sensitive testament to the incredibly diverse expressions of contemporary reality in urbanizing

China. It shows how people's material culture is expressed through personal belongings that tell stories about their lives and fortunes, their joys and heartbreaks, as well as their persistent failures and tenacious dreams.

In this body of work, families from various backgrounds pose with the contents of their homes, carefully set up outside their places of dwelling, and face the camera with their personal belongings. There are women and men, boys and girls, babies and grandparents, young people and middle-aged parents. They are Han Chinese, Kazakhs, Hui Muslims, Li people, and various other ethnic minorities. They are poor, salt of the earth peasants, straining to eke out the most basic living, and they are wealthy bourgeois nouveau riche. They are barely middle class urbanities, and they are affluent peasants. In short, they occupy the rainbow of social stratifications. Their homes tell tacit visual stories about changing fortunes, modernization and the character of distinctive local architectural traditions that are rapidly being demolished. There are traditional baked clay roof tiles, and painted, gabled eves; there are sturdy thatched roofs and handmade mud and straw brick walls; there are walls of bamboo, and walls of stone, walls of red brick, cement and steel; and there are Yurts made of tanned animal pelts, and the self-designed modernized room.

Their possessions are poignant and pedestrian in turn. There are quotidian objects so banal that the very fact their owners saw fit to take them out to be photographed speaks volumes about the economic state of the families. There are fine and fancy things as well, antique furniture, ink paintings, and quaint curios. There are chickens and pigs, donkeys and horses, sheep and goats. And there are tools and instruments of labor. From the farm to the kitchen, the fields to the factories, from fishing nets to drying baskets, we see the ways that people strive to make their livings and their livelihoods in a rapidly changing world where their traditional ways of life. China's natural world finds its place here as well, from the sunflowers that raise colonies of seeds-the favorite snack of the Chinese Everyman-to the popular staple corn, from nearly barren yellow earth to sprawling grasslands, from bamboo groves to deciduous trees, from maple to oak, we see a farrago of color and agricultural bounty from across the Chinese landscape, and we see poverty, drought, soil erosion and environmental degradation as well.

The stunning geographic scope of China is also captured across the breadth of these images-from the Turpan desert of Xinjiang, to the white sand beaches of Hainan, from the waterways of Jiangnan to the countryside of Henan.

In The Family Belongings of Chinese People, Ma Hongjie's lens offers us a gaze across China that is both deep and wide, both impartial and yet compassionate. A journey through the pages of this book takes us into China's vast and great diversity, belying facile myths of uniformity and unity, and forcing us to question anew our assumptions about the basic nature of this nation as it undergoes tremendous, world-historical change.

If these images deliver any single message, that message would be: the story of China was once a story of romance and tragedy, irony and comedy. It is a story of people who are tenacious and fatalistic, modest and ambitious, humble and unassuming, but also proud and unyielding. More importantly, the collection of images indicates that the story of China is an unfinished story and the arc of history leads us to a place where we don’t know yet. This is not the China of glossy propaganda pamphlets, tourist brochures or well-intentioned mass media drama. Instead, these images hint at the ways in which the story of China is plural, and still unfolding-with decentered, heterogloss, polyglot narratives, competing narrators, and myriad protagonists who are neither hero nor villain but undeniably human.

1963年出生于河南省洛阳市,回族。

1987年 开始自学新闻写作、散文写作。

1994年 武汉大学新闻摄影专业毕业。

1994年 任《河南经济日报》摄影记者。

1997年 任《河南法制报》摄影记者。

1998年 任《焦点杂志》特约记者。

2001年 任《百姓信报》摄影记者。

2001年9月, 参加首届平遥国际摄影大师班培训。

2003年 任《豫情时报》摄影记者。

2004年8月, 考察长江源头并进行为期一个月的拍摄。

2004年至今 任《中国国家地理》杂志社图片编辑。

2005年5月, 独自对青藏铁路进行一个月的考察拍摄。

2006年10月,进入可可西里无人区,进行为期40天的考察拍摄。

2007年1月, 在河南省、陕西省考察拍摄“中华姓氏起源”的专题。

2008年5月, 应The North Face邀请,前往美国约塞米蒂国家公园(Yosemite National Park) 拍摄。

2008年8月, 沿着黑龙江进入俄罗斯,最后到达入海口进行考察拍摄。

2008年10月,前往伊朗访问拍摄。

2009年4月, 前往马来西亚考察拍摄。

2009年4月, 前往越南、印度尼西亚拍摄那里的中国人。

2009年5月, 进入中国南海海域到达曾母暗沙、北康暗沙、琼台礁、弹丸礁等南海诸岛考察。

2010年5月, 前往中国西沙群岛、中沙群岛进行考察拍摄。

2010年6月, 前往中国南沙群岛中国驻守的岛礁上进行考察拍摄。

2010年10月,前往俄罗斯远东地区、贝加尔湖等地考查拍摄。

2010年11月,前往美国拉斯维加斯、盐湖城等地拍摄。

2010年11月,前往秘鲁马丘比丘古城、印加古盐田拍摄。

2010年12月,第二次前往中国西沙群岛考察拍摄。

2011年10月,组织中国GEO组织在土耳其的展览策划。

2011年11月,受德中友好协会邀请赴德国考察德中文化周活动项目。

2012年5月, 第三次次前往中国西沙群岛考察拍摄。

2012年8月, 在德国波茨坦策展中国摄影师《中国景象》十人展。

2013年5月, 第四次前往中国西沙群岛考察,航拍西沙群岛所有的礁。

擅长拍摄社会纪实类图片,主要作品有《唐三彩》、《西部招妻》、《采石场》、《割漆人》、《采药人》、《耍猴人》、《年画人家》、《黄河上的人家》、《中国人的家当》、《中国1988~2008》、《中国南海》等20多组专题图片。

获奖:

1995年2月 专题摄影报道《幸福井前的欢笑》获得河南省好新闻二等奖。

1999年10月,摄影作品《赶场》获文化部群星奖铜奖。

2000年1月, 摄影作品获千禧年香港中国旅游摄影比赛金奖。

展览:

2012年7月,作品参加陕西《民间》摄影展。

2011年3月,《家当》在英国SEASAME画廊展出。

2009年7月,《家当》摄影作品参加意大利国际摄影节。

2009年1月-2010年1月,《家当》摄影作品参加在北欧丹麦、挪威“弥散成像”展览。

2007年12月,作品《家当》,在北京798“百年印象”摄影画廊展出。

2003年9月, 在平遥国际摄影节上举办河南十三人《乡土中原》摄影联展。

2002年9月, 摄影作品参加中国平遥国际摄影节大展。

出版:

2015年4月,出版《中国人的家当》画册。

2015年1月,出版《最后的耍猴人》一书。

2014年8月,前往东沙群岛考查拍摄。

2014年5月,出版《西部招妻》一书。

收藏:

2011年5月,出版《民本》画册。

2008年9月, 作品《荡秋千》被广东美术馆收藏。

2008年8月, 摄影作品参加中国华辰影像作品拍卖。

2004年4月, 四幅摄影作品被河南博物院收藏。

2003年9月, 四幅摄影作品被法国EGMO画廊收购。

2003年8月, 六幅摄影作品被广东美术馆收藏。

Ma Hongjie

Muslin,born in Luoyang,Henan

Specialized in social documentary photography,main works include: "Tri colored glazed pottery of the Tang Dynasty", "Western Recruit Wife", "Quarry", Cut The Painting "," Herbs "," Monkey Man "," Pictures of People "," The Yellow River People ", The Belongings Of The Chinese People," China From 1988 To 2008 "," South China Sea "

Awards

“Laughing at the Happy Well”, second award of the Henan Good News

“Fair”,bronze award of the Cultural Department

Golden award of the Millennium Hong Kong-China Tour Photo Competition

Exhibitions

Folk Exhibition,Shanxi,China

“Home Belongings”,SEASAME Gallery,Great Britain

“Home Belongings”,International Photo Festival,Italy

“Home Belongings”,Mass Imaging,Denmark & Norway

“Home Belongings”,Impression of Hundred Years Gallery,Beijing

Joint Exhibition“Local Central Plains”,Pingyao International Photo Festival Pingyao International Photo Festival

Publications

“Chinese Home Belongings”

“the Last Monkey Player”

Took photos on East Sand Islands

“Marrying Wives in western China”

Collections

Published “Citizenism”

“Swinging”,collected by Guangdong Art Museum

Participated in the China Huachen Photo Works Auction

Four Works Collected by Henan Museum

Four Works Collected by EGMO Gallery(France)

Six Works Collected by Guangdong Art Museum

中国人的家当

序 马宏杰摄影作品中未完结的中国故事

迈涯 博士

迈涯 博士

马宏杰1963年在河南省洛阳市的一个工薪家庭中出生,这似乎意味着他也将会跟随父辈的脚步。他的父母是一家国有玻璃厂的工人。在那个年代,这是一份相当稳定的工作,收入体面,住在工人集体宿舍,孩子能够就读厂子弟学校。生活尽管不宽裕,但也能满足全家人的温饱需求。马宏杰中学毕业后也在厂里工作了一段时间。工人的经历在他后来的创作生涯中影响着他的摄影视角,使得他尤其敏锐地看到老百姓日常生活的兴衰变迁和艰辛。

与很多中国人一样,马宏杰童年的大部分时光是在贫穷的农村跟祖父母和家中的兄弟姐妹们一起度过的。从孩提时起,他就有强烈的社会正义感。他的祖父驮了一辈子粮食,背部严重扭伤,腰弯成九十度,再也站不直了。马宏杰至今还记得自己上小学的时候,因为看到大伯不肯帮祖父背一袋沉重的玉米而气愤。他记得当时的自己多么渴望能为祖父母做点什么,为他们的生活减少一些艰辛。

像大部分当地人一样,马宏杰的祖父母把家安在山坡上的窑洞里。从土墙中挖出一个不大的开孔做窗,再挖出一扇小门,好让那一点点微弱的自然光透过窗纸照进家里。马宏杰特别想从玻璃厂里弄一块玻璃回来,给祖父母置一扇像样的窗,让屋里更亮堂些。善良的祖母严厉训斥了他,说即便家里的窗子永远安不上玻璃也比偷东西强。祖母除了强调道德规范,也特别向马宏杰灌输受教育的重要性。他就学期间,祖父母在一年之中相继去世,他偷玻璃的计划始终没有得以实现。尽管祖父母已经不在,农村劳动人民生活的艰辛和尊严却在他心中留下了深深的烙印,其精神至今仍渗透在他的作品中。

马宏杰的父亲曾梦想去念大学,也考上了,却因为祖父患病而不得不放弃这个梦想。为了照顾生病的父亲,他必须工作,结婚后有了三个孩子,可梦想却从未在心中消失。马宏杰回忆起那满是冲突、缺少温暖的家庭生活,回忆起儿时的自己多么渴望自立,他知道未来需要自己去创造,去追求。

那份追求便是摄影。通过镜头,马宏杰找到了一种观察社会的全新视角,找到了一种在他看来最有意义的对世界的题献。他1982年开始用朋友的相机自学摄影,学会了冲洗胶卷、印照片,技术越来越好,后来已经能靠为别人冲印彩色照片挣钱。两年后,他娶了一位中学同学为妻,换到拖拉机厂工作,再没有更多的时间投身摄影。他与妻子有了一个儿子,夫妻两人艰难地养家糊口。

在贫困时期,马宏杰不得不变卖自己的相机。但他并没有长时间脱离摄影,放弃不是他的风格。儿子三岁那年,他开始研习摄影理论,借来一台相机,开始向不同的平面媒体投寄摄影作品,想碰碰运气。很快,他的作品收到了相当热烈的反响。

在获得不少摄影奖之后,马宏杰终于有了信心于1994年向一家报社递交了工作申请,从工人变成了摄影记者。在1997年的早期国有企业改革中,这家报社停业了,而他也必须重新寻找生计。2004年,他开始就职于《中国国家地理》杂志,他的事业上了一个新的台阶。接下来的几年中,摄影记者的工作令他直面平常老百姓生活的种种艰辛,重新唤起了他对祖父艰难生活的记忆。

后来的十年里,马宏杰因为工作任务走遍全国各地,拍下数不清的照片。中国文化的丰饶以及中国社会和经济的巨大变革给他留下了深刻印象,叫他惊诧,他开始自发地记录中国人当下不断改变的生活状况。

他的第一本书《民本》(2010),其中的黑白照片捕捉了中国人在日常生活中的微妙脸庞。马宏杰的创作以起初的纪实性作品作为开端,逐渐转变为现在的摆拍。他这一新的创作阶段在《中国人的家当》里有最为集中的体现。

《中国人的家当》是一份敏锐的证书,包含了对都市化进程中的当代中国大环境多种多样的表达。它反映出物质文化怎样通过个人物品体现,这些个人物品中包含了人的故事,有人的生活和命运,喜悦和心酸,以及他们不断的失败和不懈的梦想。

在这一系列作品里,来自不同社会背景的家庭在于自家门口搭建的布景中,跟从自己家中搬出的物品一起摆造型,面对相机镜头。照片中,有男人和女人,男孩和女孩,婴儿和祖父母,年轻人和家长;有汉族人、哈萨克族人、回族人、黎族人和其他少数民族。他们中有的贫穷,是吃苦耐劳、心地善良的工人阶级,省吃俭用,竭力维持最基本的生计,也有小资新贵和富裕的农民。他们来自社会的各个阶层和角落。

他们的家也默默地参与着其中的故事,有命运的改变,有现代化,也有那些不断被拆毁的当地特有的传统建筑。在照片中你能看到用传统工艺烧制而成的陶土瓦和歇山顶彩绘斗拱、坚固的茅草屋顶,和用泥土和稻草搅和做成的砖做的泥墙,还有竹墙、石墙、红砖和水泥钢筋,以及鞣制的动物皮毛盖成的蒙古毡房,以及房屋主人自行设计的现代化房屋。

他们所拥有的物品也同房屋一样,反映着其生活状态和经济条件。其中有精美高级的物品,古董家具、水墨画、古色古香的珍奇摆件,也有极其平常的日常用品。有鸡和猪,驴和马,绵羊和山羊,还有机械工具。从农场到厨房,从田野到工厂,从渔网到晾晒干货的篓子,我们目睹着人们如何在一个剧变中的世界谋求生计。

中国的自然景观在这本作品集中也有它的一席之地,从新疆的吐鲁番盆地,到海南的白沙滩,从江南的水道,到河南的乡村,从一片片向日葵,到广受欢迎的主食玉米,从近乎荒芜的黄土地,到无边蔓延的芳草地,从竹林到落叶树木,从枫树到橡树,我们看到色彩的丰富和横跨中国土地的农耕收获,同时也看到了贫穷、干旱、土地侵蚀和环境恶化。

马宏杰的镜头给予了我们看中国的视角,既深入又宽泛,既客观又深情。翻阅此册,辽阔的、拥有多样性的中国便展现在你眼前,由此证明关于其单调统一的说法之伪,使我们重新审视对这个正在经历巨大历史性变革的国家的本质的假设。

如果这一幅幅画面传达了某种信息,那必定是这样的中国的故事:既浪漫又悲剧,既讽刺又幽默。这故事中的人们既坚韧又认命,既谨慎又野心勃勃,既谦逊又平易,既骄傲又不屈。更重要的是,这些汇合的画面告诉我们,中国的故事是未完成的故事,前方的路于我们是未卜的。这已不再是充斥着虚浮政府宣传手册、旅游指南和满是正面和积极的电视剧的中国。这些画面暗示我们,中国的故事是多样的,是未完成的,多种流派、声音和语言并存,共同讲述自己的故事。这里有数不清的主角,他们既非英雄也非恶霸,不过是不折不扣的普通人。

关于马洪杰的摄影作品《中国人的家当》

王春辰 博士

《中国人的家当》系列影像作品立足于这样的时代转换,去捕捉我们生活中的物品,以物的形态去透射寄寓其中的人的内在属性。这样,《中国人的家当 》系列作品就成为检视中国生活情境的视觉图景。它们不仅是解读当下中国社会生活的图像文本,也昭示了影像作为艺术所具有的特殊价值和功能。

影像作为艺术不是被动地记录现实,而要体现出艺术家积极介入现实的主体意识。《中国人的家当》这组作品充分显示了影像艺术的这种特殊功能。为拍摄作品, 摄影师走访了中国的许多地区,有意识地去选择那些最有代表性、最有中国当下生活特征的场景。

《中国人的家当》构成的图景向我们揭示了当下中国社会生活状态的内部结构,将原生态家庭生活呈现出来,以物的形式展示出中国当代环境中的生活哲学。在这种主观寻找中国生态的过程中,艺术家建构起现实与虚构之间的关系:真实的内部空间被虚拟地呈现在外部空间中,将中国家庭的境遇展现出来,直接穿透观众的视觉目光。这看似悖论的场景实际上是中国历史大转型中被遮蔽了的东西。如果不是艺术家用直接的方式呈现出如此明确的家当图景,我们会对中国人家庭中的器物组织视而不见,即便见到也不思考,这是艺术家巧用影像艺术强力介入我们的知觉的结果。《中国人的家当》的每一个组成部分都是中国当代社会的生活信仰与生存状况的见证,它们见证了中国现代化进程中生活方式的变与不变。在现实与想象的疏离空间中,《中国人的家当》以视觉启示的方式发现了我们置身其中的生活逻辑,从而确证了中国在全球大变局中的具体在场。

The Family Belongings of Chinese People

Preface

An Unfinished Chinese Story in Ma Hongjie’s Photography

Born in 1963 in Luoyang, Henan Province, from a working class

Family, Ma Hongjie seemed would follow the footsteps of his parents and grandparents. Both of his parents worked at a state-owned glass factory, which was a quite steady job at the time with decent pay, arranged apartments, and schools for their kids. Although it didn’t ensure an abundant life, it was enough to meet the family's modest needs. When he graduated from middle school, Hongjie joined his parents at the factory. The experience of working at a factory later has an influence on his imagery, vision, and gave him the sensitivity to observations of family vicissitudes and the people's struggle in their life.

Like many people in China, during Ma’s childhood, he spent most of time in the impoverished suburban countryside with his grandparents and siblings. Since he was a child, he had had a strong sense of justice. At the time, his grandfather had hurt his back, so every time he needed to carry packages of grain, he had to wrench the back into a 90-degree angle to be able to stand upright. Ma still remembered that he felt angry because his paternal uncle refused to help his grandfather with carrying a heavy bag of corns. He always wanted to help even as a little boy, to help with anything that somehow making the grandparents' life easier.

Same as many local people in the village, Ma Hongjie's grandparents built their home in a hillside cave. In order to see the natural light, they had to carve out a tiny door and a small hole for the window. Hongjie wanted to steal a piece of real glass from the factory to cover the window space. After hearing about his plan, his grandmother gave him a lecture about “Never to steal, even life is hard”. Other than insisting her strict moral upbringing to Hongjie, grandmother told him that she believes in the importance of education. Years later, both grandparents died when Hongjie was still in school. However, the influence of his grandparents and the experience of living in rural countryside are revealed in his photographic work.

Ma Hongjie's father had dreamed of studying in college and he did pass the test but eventually had to give up because of his father had gotten tuberculosis. Ma’s father had to go to work to take care of his ailing father, had to get married. The dream was still in his heart, even later had three children.

Hongjie recalls his childhood life with family conflicts and hard time, he was long in finding happiness in his own life and earning a bright future by himself.

The pursuit later was photography. Through the language of lens, Ma

Hongjie discovered a whole new vector for investigating society and inscribing himself into the world in a way that made it meaningful for him. In 1982, he discovered the power of the camera and began to teach himself to take pictures with the camera of a friend. He learned to develop film and print his own photographs and became good enough to start making money developing color photographs of other people. After two years, he got married to a woman with whom he had gone to middle school, and went to work in a tractor factory, leaving him no time to do photography. They had a son, and struggled to make ends meet in the changing economy. During these economic hard times, Hongjie had to sell his camera. But he could not keep away from photography for long and giving up was not his way. When his son was three, he started reading up on photographic theory and borrowed a camera once again so he could begin to submit his pictures to various print media to see what could come of it and discovered that his work was enthusiastically received.

After his photographs won several prizes from various magazines, in 1994, Ma Hongjie worked in a newspaper company and made the unlikely transition from a worker to a photojournalist. In 1997, however, during an early wave of enterprise reform, his newspaper was shut down and he had to seek another position. Then in 2004 he began to work for Chinese National Geography, taking his career to a whole new level. Over the next few years, his work as a photojournalist exposed him to the struggles of ordinary people and rekindled his memories of the bitterness of his grandfather's life.

Over the next decade, Ma Hongjie traveled the country on assignment taking countless pictures. The cultural richness of the Chinese people, and the enormous changes taking place in society and the economy impressed him, and he began to self-consciously document the changing conditions of their lives.

His first book, Grassroots (2010), is a tome of black and white photographs that captures the many subtle faces of everyday life in China. Ma Hongjie's practice has now evolved from its documentary roots and has crossed the boundary into contemporary, staged photography. The strongest works from this new practice of his come together in this volume, The Family Belongings of Chinese People.

The Family Belongings of Chinese People are a sensitive testament to the incredibly diverse expressions of contemporary reality in urbanizing

China. It shows how people's material culture is expressed through personal belongings that tell stories about their lives and fortunes, their joys and heartbreaks, as well as their persistent failures and tenacious dreams.

In this body of work, families from various backgrounds pose with the contents of their homes, carefully set up outside their places of dwelling, and face the camera with their personal belongings. There are women and men, boys and girls, babies and grandparents, young people and middle-aged parents. They are Han Chinese, Kazakhs, Hui Muslims, Li people, and various other ethnic minorities. They are poor, salt of the earth peasants, straining to eke out the most basic living, and they are wealthy bourgeois nouveau riche. They are barely middle class urbanities, and they are affluent peasants. In short, they occupy the rainbow of social stratifications. Their homes tell tacit visual stories about changing fortunes, modernization and the character of distinctive local architectural traditions that are rapidly being demolished. There are traditional baked clay roof tiles, and painted, gabled eves; there are sturdy thatched roofs and handmade mud and straw brick walls; there are walls of bamboo, and walls of stone, walls of red brick, cement and steel; and there are Yurts made of tanned animal pelts, and the self-designed modernized room.

Their possessions are poignant and pedestrian in turn. There are quotidian objects so banal that the very fact their owners saw fit to take them out to be photographed speaks volumes about the economic state of the families. There are fine and fancy things as well, antique furniture, ink paintings, and quaint curios. There are chickens and pigs, donkeys and horses, sheep and goats. And there are tools and instruments of labor. From the farm to the kitchen, the fields to the factories, from fishing nets to drying baskets, we see the ways that people strive to make their livings and their livelihoods in a rapidly changing world where their traditional ways of life. China's natural world finds its place here as well, from the sunflowers that raise colonies of seeds-the favorite snack of the Chinese Everyman-to the popular staple corn, from nearly barren yellow earth to sprawling grasslands, from bamboo groves to deciduous trees, from maple to oak, we see a farrago of color and agricultural bounty from across the Chinese landscape, and we see poverty, drought, soil erosion and environmental degradation as well.

The stunning geographic scope of China is also captured across the breadth of these images-from the Turpan desert of Xinjiang, to the white sand beaches of Hainan, from the waterways of Jiangnan to the countryside of Henan.

In The Family Belongings of Chinese People, Ma Hongjie's lens offers us a gaze across China that is both deep and wide, both impartial and yet compassionate. A journey through the pages of this book takes us into China's vast and great diversity, belying facile myths of uniformity and unity, and forcing us to question anew our assumptions about the basic nature of this nation as it undergoes tremendous, world-historical change.

If these images deliver any single message, that message would be: the story of China was once a story of romance and tragedy, irony and comedy. It is a story of people who are tenacious and fatalistic, modest and ambitious, humble and unassuming, but also proud and unyielding. More importantly, the collection of images indicates that the story of China is an unfinished story and the arc of history leads us to a place where we don’t know yet. This is not the China of glossy propaganda pamphlets, tourist brochures or well-intentioned mass media drama. Instead, these images hint at the ways in which the story of China is plural, and still unfolding-with decentered, heterogloss, polyglot narratives, competing narrators, and myriad protagonists who are neither hero nor villain but undeniably human.

Dr. Mai Ya

Ma Hongjie’s Photography Series: “The Family Belongings of Chinese People”

By Wang Chunchen

The process of modernization has accelerated the structural transformation of Chinese society.

In some ways, this transformation has been quite extensive. This historical context offers art both great opportunities and also challenges. It demands not only the suitable art forms, but also artists' observations and responses this change in context. The realities of life call for a contemplative art.

Ma Hongjie's photographic series The Family Belongings of Chinese People roots in this transitional era, and focuses on the materials of daily life for Chinese families, aiming to reflect the human nature embedded in them. Thus, this series offers an examination of the life conditions of the Chinese people. Images from this series are at once pictorial texts that interpret the life presence in Chinese society and a demonstration of the special value and function of photography as art.

As an art form, photography does not passively record reality. Rather, it demonstrates artists' participation in shaping the real world. The Family Belongings of Chinese People show this special function of images quite well. To make this photographic series, Ma Hongjie visited a number of areas and regions in China,

Selecting the most typical residential images reflecting the current life condition in China.

The lens offered by The Family Belongings of Chinese People reveals the interior structure of the conditions of contemporary life in Chinese society. It brings out the underlying family life and interprets the attendant life philosophy through tangible materials from the contemporary social context. While actively seeking to articulate life conditions in China, the artist establishes a relationship between reality and the imagination: the actual domestic space is presented in the open air, bringing to light China's home conditions and penetrating the viewer's vision. These seemingly paradoxical scenes are in fact what have been hidden during the transformation of Chinese society. Without taking account of the family belongings that are clearly shown by the artist, we might have ignored the material content of Chinese families' lives, or think little about it. Thus, the artist uses photographic images to engage our consciousness. This body of work is a testament to the faith and condition of life in contemporary China, and evidence of what has changed and also what has remained the same during modernization. Between reality and the imagination, The Family Belongings of Chinese People locate the logic of our existence in visual inspirations, confirming the particular presence of China within the larger scope of grand global change.

In some ways, this transformation has been quite extensive. This historical context offers art both great opportunities and also challenges. It demands not only the suitable art forms, but also artists' observations and responses this change in context. The realities of life call for a contemplative art.

Ma Hongjie's photographic series The Family Belongings of Chinese People roots in this transitional era, and focuses on the materials of daily life for Chinese families, aiming to reflect the human nature embedded in them. Thus, this series offers an examination of the life conditions of the Chinese people. Images from this series are at once pictorial texts that interpret the life presence in Chinese society and a demonstration of the special value and function of photography as art.

As an art form, photography does not passively record reality. Rather, it demonstrates artists' participation in shaping the real world. The Family Belongings of Chinese People show this special function of images quite well. To make this photographic series, Ma Hongjie visited a number of areas and regions in China,

Selecting the most typical residential images reflecting the current life condition in China.

The lens offered by The Family Belongings of Chinese People reveals the interior structure of the conditions of contemporary life in Chinese society. It brings out the underlying family life and interprets the attendant life philosophy through tangible materials from the contemporary social context. While actively seeking to articulate life conditions in China, the artist establishes a relationship between reality and the imagination: the actual domestic space is presented in the open air, bringing to light China's home conditions and penetrating the viewer's vision. These seemingly paradoxical scenes are in fact what have been hidden during the transformation of Chinese society. Without taking account of the family belongings that are clearly shown by the artist, we might have ignored the material content of Chinese families' lives, or think little about it. Thus, the artist uses photographic images to engage our consciousness. This body of work is a testament to the faith and condition of life in contemporary China, and evidence of what has changed and also what has remained the same during modernization. Between reality and the imagination, The Family Belongings of Chinese People locate the logic of our existence in visual inspirations, confirming the particular presence of China within the larger scope of grand global change.

豫公网安备 41019602002106号

豫公网安备 41019602002106号