王豫明

1957年生于重庆,独立艺术家。

获奖;

2002年 《早晚》获2002年“平遥国际摄影大展阿尔卡特中国优秀摄影画册”三等奖 平遥 山西

2005年 获韩国东江国际摄影节“最佳国外摄影师奖” 东江 韩国

2009年 《圆公园》获爱普生摄影年赛“评委提携大奖” 上海

2013年 《粉彩金莲》 获河南省首届陶瓷艺术展金奖 郑州 河南

2014年 《梅问》系列作品首届中外陶艺家原创新品大赛金奖 景德镇 江西

2015年 《梅问》系列作品2015首届中国瓷画双年展获奖提名 景德镇 江西

展览:

个展

2015年 《这样》 “云水居艺术空间” 洛阳 河南

2015年 《梅问》 “栖霞岭上艺术空间” 杭州 浙江

2014年 《梅问》 “青花国语瓷绘艺术机构” 景德镇 江西

2012年 《青趣》 “左岸瓷绘艺术机构” 洛阳 河南

2012年 《景致》 大理国际摄影会 大理 云南

2007年 《不是》 “咏春画廊” 洛阳 河南

2006年 《乡里人城里人还有景和花》 5+1画廊 洛阳 河南

2005年 《早晚》 韩国东江博物馆 东江 韩国

2003年 《呓语》 平遥国际摄影大展 平遥 山西

群展

2015年 《中灵山》 安心.微艺术空间 洛阳 河南

2015年 《响沙湾》 “春在”影像联欢 洛阳 河南

2014年 《梅问》 “中国首届陶瓷艺术双年展”景德镇 江西

2014年 《梅问》 “百家争鸣陶瓷艺术展” 景德镇 江西

2014年 《粉彩金莲》 “本土与景飘陶瓷艺术展” 北京

2013年 《粉彩金莲》 河南省首届陶瓷艺术展 郑州 河南

2013年 《景致》 全摄影画廊 上海

2011年 《四说新语(瓷绘)》 中国书法院 北京

2010年 《这里》 河南美术馆 郑州 河南

2010年 “Open Frame – New Landscape Photography from China”新加坡YAVUZ Fine Art

2010年 《荷》 周围艺术画廊 上海

2009年 《圆公园》 三尚画廊 北京

2009年 《城·惑》 全摄影画廊 上海

2008年 《景致》 山水文苑艺术中心 北京

2008年 《呓语》 河南美术馆 郑州 河南

2008年 和谐石佛国际艺术展 石佛艺术公社 郑州 河南

2007年 《景致》 BOLZANO 意大利

2006年 《景致》索菲特2006中国当代艺术展 西安 陕西

2006年 《自己的城》 山东青州博物馆 青州 山东

2005年 天安门FOAM博物馆 阿姆斯特丹 荷兰

2004年 火柴MATCHEVENT多媒体国际艺术展 798 北京

2003年 中国人本—纪实在当代 广东美术馆 广州 广东

2003年 “平遥在巴黎 ” 巴黎 法国

出版;

2013年 《王豫明绘瓷》 (本真堂出品)

2013年 《青趣--王豫明绘瓷作品》 (人文艺术出版社)

2011年 《王豫明绘瓷作品集》 (人文艺术出版社)

2011年 《红外摄影作品集》 (中国图书出版社出版社)

2005年 《2005中国当代美术现象考查-影像卷》(2005年)

2004年 《2004中国当代美术现象考查-影像卷》(2004年)

2003年 《阻挡》个人作品集(2003年)

2002年 《早晚》个人作品集(2002年)

收藏;

2010年 《这里》 (三件) 河南美术馆

2010年 《天香(瓷)》(二件) 意大利艺术机构

2008年 《景致》 (二件) 意大利艺术机构

2006年 《呓语》 (四件) 河南博物院

2005年 《早晚》 (二十件) 韩国东江摄影博物馆

2003年 《阻挡》 (一件) 广东美术馆

Wang Yuming

1957 Born in Chongqing.

Current Lives in Luoyang, working as a freelance photographer.

Awards

2015 Plum Blossom Ask, Golden Prize of the First National and International Ceramist New Work Competition, Jingdezhen

2014 Plum Blossom Ask, 2015 Chinese Porcelain Painting Biennale (Nominated)

2013 “Pastel Jinlian”by Henan Province, the first ceramic art exhibition Gold Award

2009 “circle” Epson photography played “Park won awards judges up”

2005 The Best Foreign Photographer at The International Photography Festival of East River, Korea East River, Korea.

2002 Morning and Evening, Pingyao International Photography Festival Al Carter

Third Prize of Chinese Excellent Photo Album "Pingyao Shanxi”

Solo Exhibitions

This Way, ‘Yun Shui’ Art Space, Luoyang, Henan

Plum Blossom Ask,Xixia Lingshang Art Space, Hangzhou, Zhejiang

Plum Blossom Ask, Qinghua Art Institution, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi

2012 Green Interest, Left Bank Porcelain Art Center, Henan

2012 Scenery, Dali international photography of Dali of Yunnan

2007 Is Not, Wing Chun Gallery, Luoyang, Henan

2006 Village City people and scenery and flowers, 5+1 Gallery, Henan, China

2005 Morning and Evening, Dongjiang Museum of Korea, South Korea

2003 Balderdash, Pingyao International Photography Exhibition, Shanxi, China

Group Exhibitions

2015 Zhongling Mountain, Anxin-Micro Art Space, Luoyang, Henan

2015 “Sounding Sand Bay”,”Chun Zai”Image Gala, Luoyang, Henan

2014 Pastel Nasturtiums, Jingdezhen Museum of Contemporary Art, Jiangxi, China

2013 Pastel Nasturtiums, The First Henan Ceramic Art Exhibition, Zhengzhou, Henan, China

2013 Scenery, Quan Photography Gallery, Shanghai

2011 Shi Shuo Xin Yu (porcelain painting), China Calligraphy Institute, Beijing

2010 Here, Henan Art Museum, Zhengzhou, China

2010 Open Frame - New Landscape Photography from China, YAVUZ Fine Art, Singapore

2010 Lotus, Zhou Wei Art Gallery, Shanghai

2009 Circle Park, Three Shang Gallery, Beijing

2009 City·Puzzle, Quan Photography Gallery, Shanghai

2008 Scenery, landscape building of Beijing Art Center

2008 Balderdash, Henan Zhengzhou Art Museum, Henan

2008 Harmonious Buddha Stone Sculpture International Art Exhibition, Zhengzhou, Henan, China

2007 Scenery, BOLZANO Italy

2006 Scenery, Sofit 2006 Chinese Xi'an Contemporary Art Exhibition, Shananxi, China

2006 Shandong City, Qingzhou Shandong Museum, Shandong, China

2005 FOAM Museum of Amsterdam Tiananmen, Holland

2004 MATCH EVENT Multi-media International Art Exhibition, 798 Art District, Beijing

2003 Chinese People - Documentary in the Contemporary China, Art Museum of Guangzhou, Guangdong

2003 Pingyao in Paris, Paris, France

Publications

2013 “Wang Yuming painted porcelain” (true church produced)

2013 “green corner—— Wang Yuming painted porcelain works” (Arts and humanities Press)

2011 “Wang Yuming painted porcelain works” (Arts and humanities Press)

2011 “infrared photographic works” (China Book Publishing Press)

2005 Chinese contemporary art phenomenon study image volume" (2005)

2004 Chinese "contemporary art phenomenon study image volume" (2004)

2003 “barrier” personal collection (2003)

2002 Morning and Evening " personal collection (2002)

Collections

2010 “Here” (three pieces) Henan Art Museum

2010 “Tian Xiang (porcelain)” (two) the Art Institute of Italy

2008 “scenery” (two pieces) the Art Institute of Italy

“balderdash” (four pieces) of Henan Museum

2005 Morning and Evening (Edition of 20), The East River Museum of Photography, Korea.

2003 “barrier” (one piece) Guangdong Museum of Art

本雅明在描述摄影的意义时强调说:大自然对着镜头和眼睛说了各不相同的话。 这句话可以说意味深长。我想,本雅明的意思是,当人们以为摄影的拍摄和眼睛的观看相互重合时,摄影的结果,也就是照片本身,却恰恰证明这种看法是多么的错误。也就是说,我们既不能把照片看成是纯粹的记录,以为它就是构成人类视觉记忆的唯一材料,同时,我们又不能把照片看成是完全主观的产物,以为它无法重建我们的观看历史。一部摄影史已经明白无误地告诉我们,一方面,摄影机在记录自然,另一方面,摄影机还在筛选自然。记录自然的意思是,尽可能让自然呈现出它原本的面貌。而筛选自然的意思则是,让自然呈现出拍摄者可以接受的形式。其实,我们只有在后者的意义上,才把拍摄的结果解释成“作品”。

如果这种看法是可以成立的,我们马上就能获得一个理解摄影史的角度。在如何运用一部机器记录自然物象的外观方面,摄影史提供了无以伦比的例证,这一点无须说明。同时,由于“作品”的“形式”是构成摄影产品的一个视觉前提,所以,我们同样可以把一部摄影史读解成类似“艺术史”那样的历史。正是这个意义上,摄影史才获得了人文的价值,对摄影的解释才具有美学的意义。问题是,一旦这种看法成立,人们往往会用后者来取代前者,也就是把摄影美学化。我想,这大概是摄影界,尤其是中国的摄影界,在长达半个世纪中,对“沙龙摄影”情有独钟的一个原因。

其实,这种现象不独中国才有。翻阅西方摄影史,我们同样看到类似的现象。

理解了上述现象,我觉得就可以理解出现在摄影界的一系列现象。因为,一旦把摄影纳入艺术史描述的范围, 那些原本针对旧有样式进行颠覆与创新就变成了摄影发展的常态。甚至,在一个崇尚创新的氛围中,如果没有一点新东西,被淘汰的命运就可能是无法避免的事情了。

我怀疑王豫明在内心深处也潜藏着这么一丝颠覆精神,否则就无法解释他的几组作品。首先,我看得出来,王豫明是在一个常规的摄影上下文中开始个人探索的。在过去十来年中,这个摄影上下文的主流,可能真的和一场纪实摄影运动有关。许多人,我说的是那些多少对潮流与环境有些敏感的摄影师们,或多或少地放弃了流行中国摄影界的“陈复礼”风,不理会关于“摄影艺术”的一系列呓语般的唠叨,把镜头指向了广大的民间社会。尽管我没有做过什么统计,但我相信,这三十年来,通过摄影师们的镜头所留下来的历史,可能大大超过自摄影传入中国以来的任何一个历史年代。这场纪实摄影运动,可以从王豫明的若干作品中看到某些奇特的影子。

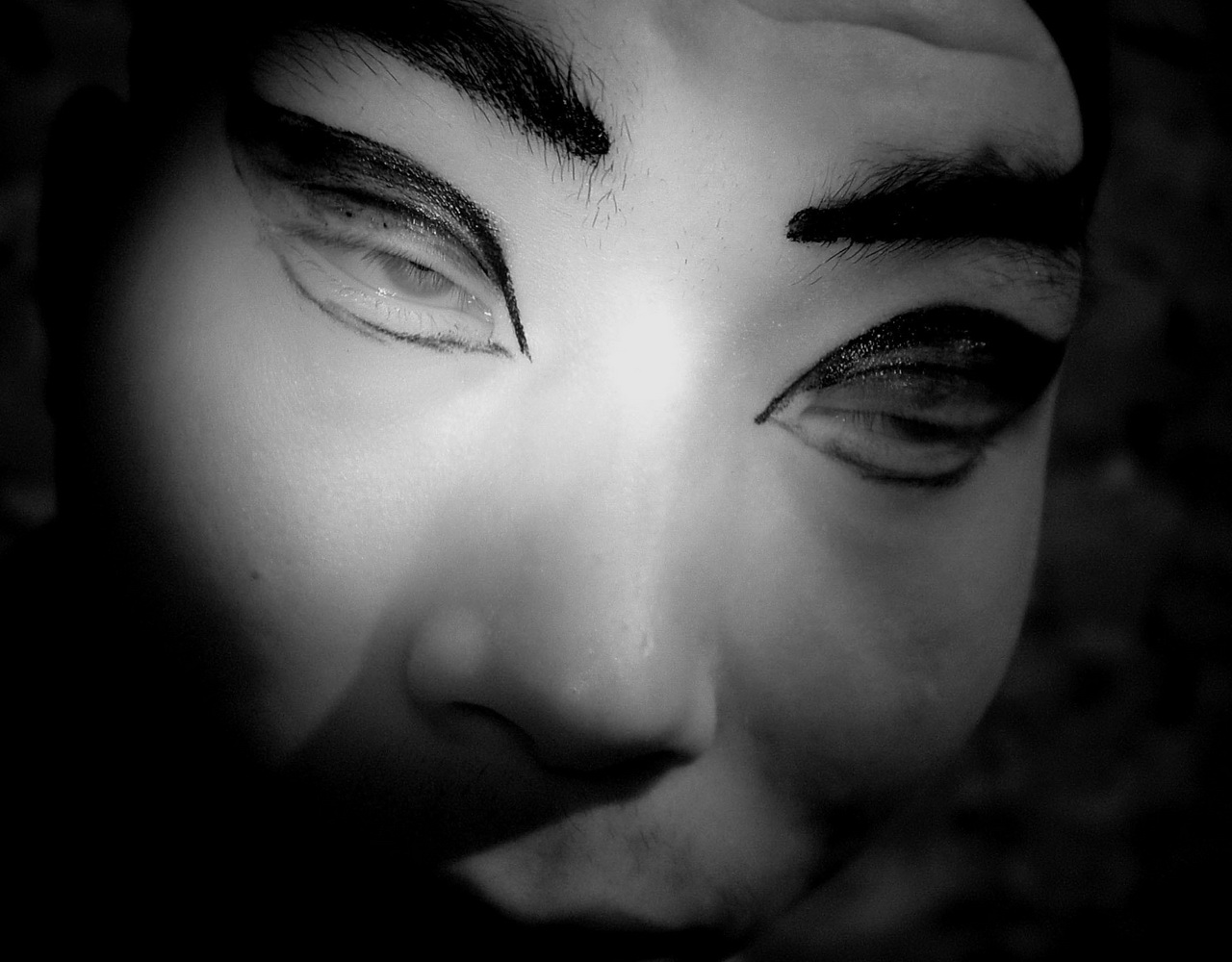

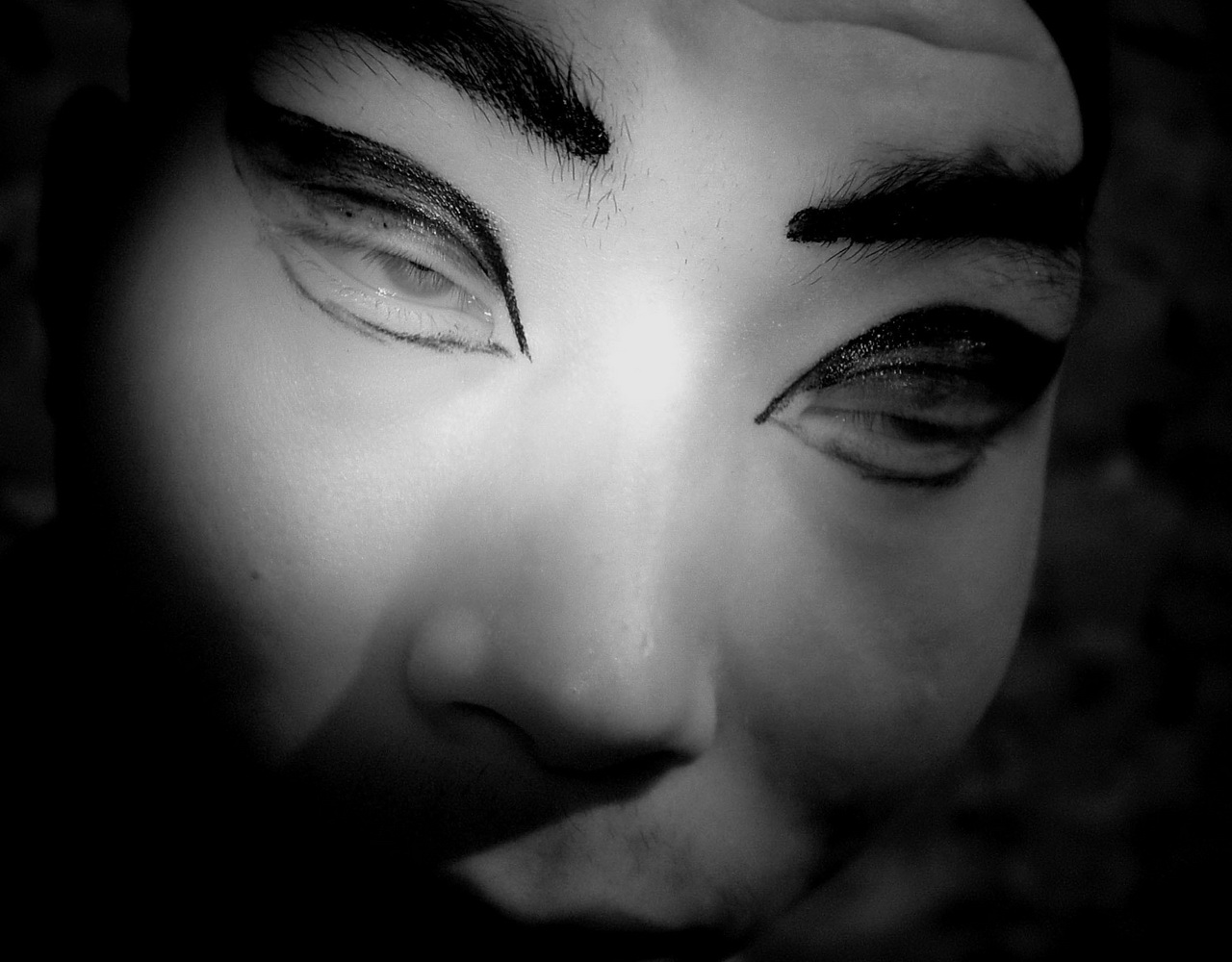

但是,正因为他成长自那个所谓“纪实”的环境中,同时又有些许的颠覆精神,这就决定了他的变异方向无法离开“纪实”。我从他的《呓语》系列中,倒是看出一种无奈与放任。《呓语》拍的是黑夜中的城市,而且拍摄方式是偶发式的。从作品中可以看出作者刻意放弃那种常见的手法,比如寻找一个主题、固定一种拍摄方式、甚至拍摄角度,然后用图像解释之。我猜想王豫明刻意让自己漫无目标地行走,想象自己是一个真正的梦游者,在闲逛中,在甩手中,下意识地去按动快门,好完成一个又一个的瞬间。他舍弃通常的意义,通常的影像效果,通常的影纹层次,通常的让人激动的拍摄对象。我甚至怀疑他不看、或者少看镜头,以减少习惯上的构图积习。他希望自己不是一个拍摄者,而是一个真正的梦游者,然后从梦眼中认识城市。“呓语”是一个很好的关键词,点出王豫明内心所希望的状态。有意思的是,我仍然不认为王豫明是真的“呓语”,他针对一种熟悉的影像传统,一种人们已经习惯的城市形象,而给出自己的答案。问题是,他的答案本身并不是呓语,而是关于“呓语”的影像定义。这就像一个通常意义上的摄影师,他总是从取景框中截取自然。现在,王豫明想颠覆这种“截取”,他的对象与其说是城市,不如说是取景框。于是,他采用了一瞥的姿态,也就是不用全眼,而是用眼角,不留痕迹地把一座城市的潜在形象揭示出来。同样的方式呈现在他另一组命名为《早晚》的人物作品中。这些作品呈现出一种奇特的视觉效果,这种效果,按照作者“技术化”的解释,是用红外线夜拍镜照下来的。作品的人物双眼闪着一点白光,徒然增加了视觉的“幽灵感”,让人惊诧不已。王豫明也发现这种效果非常符合他对“呓语”的想象,不仅塑造出另一种城市的形象,而且还塑造出另一种人的存在。这正是他所切盼的。我以为王豫明运用这种镜头可能带有一定的偶然性,但当他发现“视觉幽灵”真的成为作品事实后,他就无法放弃这种技术了。在他看来,技术在“呓语”中已经消失,剩下的就是真实的灵魂闪现的瞬间。在我看来,这不是镜头人的人物,而是镜头之余的产物。

证明王豫明仍然在纪实的上下文中工作的证据是他的另外两组作品,反映“非典”流行期社会疯狂举动的《阻挡》系列,以及关于民间神坛上各式偶像头部的《标准像》。在《标准像》中,王豫明和观众共同分享一种喜悦,对那些乡人们只能朝拜的、而其实在形象上千奇百怪的偶像作一次深入观察。一般而言,朝拜者是不敢正视那些偶像的,所以他们无法仔细分析制作者在制作偶像时的种种意图,在他们以上中,偶像只有类型的意义,从来没有想象过,这些偶像的“个性”,倒是对人间社会的一种反衬与描述。现在,王豫明把偶像拍下来,而且是以“标准照”的方式,等于通过镜头剥离其崇拜性质,还原其中的世俗成份。同样,当那些给非典弄得神经质的村民们认真地站在村头,阻挡着“真实”的非典进入时,他们也一下子成为象征性的“标准”。其实,所有这一切都具有奇特的象征意味。在一个突然爆发疫情的地方,一个公共医疗系统几近崩溃的国度,对非典的恐惧不仅是实质性的,其实也是象征性的。从这个角度看,那些摆在神坛上的小小的偶像,和庄严站在村头的守卫们,具有一种内在的一致性。王豫明这时不再用他的影像呓语了,因为,在他看来,现实比呓语更呓语化,普通镜头足以表现他的内心震动与惊诧。

本雅明是对的,自然对着镜头和眼睛说了不同的话。本雅明似乎还有一层意思没有完全点明,那就是,自然对着眼睛说的话,除了个人以外,别人听不到(个人又何尝完全听到?)。只有对着镜头说的话,别人不仅听到了,而且还看到了。只是,当别人真的听到、看到这些“话”时,这些“话”,也就是摄影作品,已经离开拍摄者,成为独立的存在,本身就构成了另外一部历史。

王豫明的图像溶到一部比他个人更广大的摄影史中时,他的“呓语”就可能演变成一群人的呓语。

王豫明:热爱生活(节选)

从他不同时期的作品中,我们可以看出王豫明一点点的放弃了纯粹的记录性视角,转而采用一种更加主观的方式和各种不寻常的角度。他的画面裁剪也不再那么“标准”,他“未对焦”的作品不再具有太多描述性效果,却更加容易唤起观者的共鸣。

他的画册《早晚》中的作品为他赢得了平遥国际摄影节的大奖。这些作品明显表现出他的创作方向的改变,它们采用了完全个人的视角。在这些作品中,不同年龄的农村男女穿着厚厚的棉袄,围着围巾,头戴软帽,沉浸在让人不安的黑暗中。他们的虹膜好像发出一种磷光(这是他采用了红外模式的结果),这些人看起来在参加神秘的仪式。他们的表情几乎都是不完整的,也都处在动态之中,好像并不知道有人在拍照。摄影师记录的是他们“过渡”的时刻:他们的眼睛半开半闭,嘴唇开开合合,头部半扭着。这些从下方拍摄的照片显得节奏很快,扭曲了眼白和虹膜之间的平衡,让他们看起来几乎有些吓人。但是,摄影师并不希望看到一种过分戏剧化的效果,而是力图表现一种悲怆、动感和激烈的感觉,这些感觉和那些占卜仪式的参加者的感觉是相近的。即使在一个外部的观察者看来,这些预言家恍惚的神情、祈祷者狂热的表现和他们沉浸之中的仪式结合在一起,产生了一种扣人心弦的效果。我认为,艺术家在这里并不仅仅局限于“记录”或是描述一个场景,而是让观者感同身受:他让观者把感情投入到了这些场景里,让他们感觉置身其中。

在比较王豫明作品中的“乡里人”和“城里人”时,我注意到他们的姿势、穿着和环境这些客观元素上有着不同。此外,他作品中的“乡里人”有着过度拥挤、近距离接触和杂乱无章的感觉,而“城里人”则体现出漠然、独立和封闭,这些特性也正是摄影师着力刻画的。

王豫明为我们展示了“乡里人”的眼睛和神情——虽然这些人都没有看镜头。在他的作品中,这些人好像在关注一件有意思的事情,对这件事情很好奇,集中精神在研究它。大部分作品中,他们在和其他人互动。而在表现“城里人”的作品中,王豫明故意从背面或侧面进行拍摄。他强调了他们面无表情的脸庞,好像他们在逼迫自己实现一种内心的宁静,以便抵御过多的外部刺激。这些人在公交车站等车的时候,眼睛看着下方的地面,打着手机或是抓着自己的包。他们上了公交之后,眼神都是朝车外看的,因为他们不想和其他人眼神相交。他们好像都在努力减少与周围人的接触。虽然他们之间的距离很近,足可以交流一个眼神或是谈话,他们却感到亟需创造出一种熟悉的、“安全的”环境,这种环境和他们实际处在的环境不同,能让他们感到自在和放松。

王豫明把一系列照片配上了声音,好像是箱式投影机中播放的一张张幻灯片,他为这个系列作品起了《标准照》这个具有讽刺意味的标题。通过这些作品,摄影师实现了进一步的转变:从他刚开始拿起相机拍摄的纪录性影像到一种自己的摄影方式,这种方式介于纪录性和观念性摄影之间。他拍摄了河南和山西等省农村地区寺庙或其它圣地中数十个神像的面庞。这些陶土或灰泥塑成的头像保存的状况各异,但一起组成了多姿多彩的面相集锦。它们大部分其实都不是艺术品,而是匠人打造的工艺品,有些质量让人称赞,有些则看起来就很廉价。这些形象极其色彩丰富:他们的脸有金色、青绿色、红色和灰色等等,而他们的眼睛也各式各样,有的仅仅是冷冰冰的一道裂缝,而有的则是让人吃惊的球形构造。可能这只是我自己的理解,但是我从他们中看到了人生百态。我认为,基于到我前面所描述的内容,他们代表的应该是各式各样的乡里人,而不是更加循规蹈矩、步调一致的城里人。

王豫明不仅是一名充满激情的摄影师,还对于古典文化十分熟悉。他会做诗,也会时常写写书法,画画水墨。可能是由于这个原因,他的热情的个性中还包含着对于美的自然的偏爱。在他创作了充满悲怆的“早晚”系列和简洁明快的禽流感作品系列之后,他拍摄了一组“景致”的照片,它们异样的美体现在不对称的构图、景深和时常出现的广阔的背景之中。此外他还采用了红外模式,突出了光亮的表面,让它们看起来像是白色的。这些图像中几乎没有人出现,但是却充满了各种让人印象深刻的人类活动的痕迹。它们展现了虽然被人类改造过,但看上去很荒凉的各种环境。而正是这种看似矛盾的特质让这些作品散发着让人入迷的吸引力。我们可以在图片中看到被垂柳围绕的菊花花床,周围还能见到古典风格的建筑。我们也能看到土地在被开垦耕作之后,处于一种半废弃的状态。这些作品中还有一些河流湖泊的景色或是大规模开垦的农村地区的鸟瞰图。它们所表达的悬停感、无声的寂静和呈现出让人感到疏远和不寻常的白色的各种植物将这些普通的环境转变成了宏大的风景图。我个人尤其喜欢这个系列的作品,钟爱它们营造出的永恒、疏远和悬停的氛围。

我记得2003年在平遥的一个展览中看过一个系列的照片。如果我没记错的话,这些照片真正的主角是城市夜景中的白色和特别突出的黑色。有的照片表现的是黑色背景中明亮的窗户,或面对这些窗户的房屋上反射的灯光,抑或是在模糊的背景中突如其来的、十分明亮的灯光——这些照片基于突然的、巨大的黑白反差,产生了少见的悬停的图像。在许多年前,我还是一个学艺术史的学生,我们讨论过卡拉瓦乔(Caravaggio)对于光线的高超运用,他能够将绘画变得充满戏剧效果和悲怆感。卡拉瓦乔至今仍然是我最欣赏的画家。在当今中国的摄影界,很多人还是处于一种记录“现实”的状态,或是虽然做了一些观念摄影的尝试,但是作品看起来既勉强,又完全没有诗意。因此,我对于王豫明敏感、开放的视野深感讶异。我想,他可能是在晚上下班回家的路上,捕捉到了自己城市喧嚣中充满启发的灯光,给我们展示了另一种现实,那里充满了黑色和白色的笔触,不自然的尖锐线条和模糊的区域。他的眼界有趣的原因不在于这些作品讲述了一个故事(我估计他对嚼舌根没兴趣),而在于它自身具有一种独特的美,这些美体现在抽象的构图中,让我们想起了水墨画中黑白的交替,而不是一个城市的夜生活。

我认为王豫明的禀赋和特质主要在于他能够捕捉周围世界中的美丽、悲怆和人性。他知道如何将这些直接表现出来,而不会采用很多浮夸和强调的手法。这是在他那双虽然不大,但是非常有活力和热情的眼中所看到的世界的表现。

When Walter Benjamin described the meaning of photography, he stated, that nature told different words in front of our eyes and lenses. When I interpreted this notion I think, that his initial meaning was to point out how the photographs, as results of shooting, cannot prove the believe that “we see what we capture”; that is to say, cameras document nature, but it also filter nature as well. Hence the two extreme commentaries on photography, which is, either the absolutely objective documenting or subjectively personal, are wrong from both sides. Photographs are not (and will not be) the only surviving visual resource of mankind, but it has its significance. It could slightly change the way we perceive our surroundings. A photographer shoots nature. A photographer also selectively shoots nature, which means the photographs are the evidence of the filtering process. It is the latter one what can be categorized as “artwork”.

A new perspective on the history of photography immediately will be established if the above are agreed.There is no need to particularly illuminate the utilizing machines to document the materialized world, as there have been so many examples; meanwhile, the “artwork” and its “form” are the prerequisites of any photographic series, which is verisimilar to the visual prerequisites of fine art, we can refer the history of photography to the history of art. As a result of the association, the history of photography, then gains values in a matter of humanism and aesthetics. However, once this opinion is accepted by the majority, a potential danger is to erase the former with the latter, which is only to understand the photography’s history in an aesthetic manner, and that explains why photographers, especially photographers in China are obsessed of the so-called salon photography.

It’s absolutely not a phenomenon occurs only in China. The western photography shares the similar situation.

An understanding of the phenomenon above will lead us to be able to thoroughly seeing through this occurrence. Because once photography is put in the realm of art history, so easily the Avant-garde turns to be normal, and in an era that innovation is highly worshiped, the fate for the normality is inevitable elimination.

I fancy that WANG Yuming subconsciously adopted the Avant-garde concept, or at least partially; otherwise it falls into an absurdity in the attempt to interpret some of his series. Yuming started his individual debut on photography with an ordinary context. The passing ten years saw the mainstream of this context, and in my opinion, it has to do with the documentary photography movement. Many, I mean those of alert to trends and political climates, had more or less abandoned the very dominated domestic “CHAN Fooklai” trend, had ignored the chatter about “the art of photography”, and switched their focus to the lower classes, which are massively existent. I assume, even without supportive statistics, that the eventful moments taken by photographers from this three decades is rapidly transcending any other eras in China’s history. Some of Yuming’s photograph series singularly reflected this movement of documentary photography.

He immersed in this movement and he is one of the Avant-garde. This combination fundamentally determines the documentary elements in his art, despite his abstract approach. Take his Murmur series as an example, the subject is cities at night and his process is rather spontaneous. Instead of the mainstream shooting method, which is to firstly is settling down the subject and the settings, then elucidating with following photographs, he let himself walking around without a clean idea. Or to be precise, he became a somnambulist, who captures the moments by clicking the shutter subconsciously. Going against the majority’s taste, he abandoned normal meaning, normal effects, normal textures and all normal exciting objects; he may not even look at his viewfinder in order to against any kind of shooting habits. “Murmuring” is a perfect word that frames the state he expected, though I don’t think he wasn’t aware of this activity; when facing the accustomed traditions on photography and a large amount of photographs on city view, his action was seemingly like visual nonsense yet his answer was the clear definition of murmuring and its imagery.

In his Morning and Evening series, the infrared ray effects gleam phosphorescence in the villagers’ eyes, of what dramatically creates a phantom-like tension. It is terrifying for the audiences, but he found, and very much pleased with this special effect, for not only it fits the imagery of “murmur”, but also it creates a city and people in another dimension. He was longing this imagery, and once he accidently discovered the infrared ray effect and its potentials as “visualized phantoms”, he never loses his interest of this technique. For him, craftsmanship has vanished in those attempts of visualizing murmurs; what are essential are the shimming moments of those real souls. For me, those who appear in his lenses are just byproducts from his viewfinders; those are definitely not portraits. Compare to normal photographers who will “cut off” nature through their viewfinders, Yuming’s approach is to cut off this “cut off” action by switching his focus to his viewfinders.

The defense series and the official portrait series prove the documentary photography influence of him. The former captured the insanity occurs in a village during SARS period while the latter captured profiles of idols on many altars. People worship those idols without looking at them; the awe they hold preventing them from questioning the craftsmen’s intention. For them, those deified statues are stereotypes; they never really imagine the varied characteristics finalized by craftsmen; not to mention the idea of those idols as foils of our society. WANG Yuming closely observed those idols and frankly captured their deified yet uncanny characters. By using the form of the official portrait, he separated their halos and extracted their earthliness. He also subtly captured the villagers being overwhelmed and their desperate yet illusory defense of the real happening SARS. Their activities became a certain symbol and standard stereotype, which create a queer symbolic implication to the whole series. It is not to say that the substance and the symbolization are completely detached from each other; in another angle, in where a domestic epidemic was infected and it happens to be in the nation where medical system was destructed, the solemn defenders of SARS and the aloof idol co-possess the inherent similarities.

Until reaching this point WANG Yuming stopped using his signature visual murmur; because for him, the reality is more like nonsense than any murmur, he intended to create; consequently any distinctive lenses would no less capture his astonishments. When WANG Yuming’s photographs dissolve into a massive panorama of photography, he murmurs, I guess, will be a group, or a whole salon’s murmur.

Walter Benjamin was right, nature told different words in front of our eyes and lenses, yet he didn’t expound what a personal experience it is. Let us recall the moment of shooting, actually no anyone else can hear what nature tells the photographer; only the photographs, of which gained their independent existence, convey the words from nature to the audiences. They made their own history.

I have often seen Wang Yuming laugh, toast his glass, sing, and jestingly incite others to merrymaking. Sometimes I’ve caught him in a sad and serious mood. His cheerfulness is certainly laden with optimism and great inner strength, yet it is also imbued with the melancholy and resignation of those who know that the human condition can be difficult and full of hardships, and that it is wiser to face even its less pleasurable aspects by experiencing them intensely, like gulping down a glass of some sour liquid rather than feigning a superficial indifference or convenient detachment.

“Comrade Wang,” as I teasingly like to refer to him, recalling a time in which the term was ubiquitously used, and was invested with a value that went beyond pure form, etiquette, or custom, is a person who would give everything for his friends, who lives a very intense social life, and is always ready to consider the needs of others before his own. At times this attitude turns against him, even affecting his physical well-being, while at others his warm-hearted, generous nature must endure the blows of a fast-paced, busily industrious daily routine and his lack of regard for his physical health.

Wang Yuming was born in Chongqing of Sichuanese father and later moved to Henan, an “ancient” province, from which I think he has absorbed a few deeply traditional aspects. Henan is a region I especially love, partly because of its quite numerous extant examples of Han art, of which I am an enthusiast. The tumuli scattered throughout the countryside, which mark where the tombs of the nobility once stood, seem to conjure up the voices of a great civilization. This is a province whose people still live according to modes of behaviour that are based on deep mutual respect. When such modes do not result in the mere empty or hypocritical enactment of the rules of etiquette, which can happen anywhere, such forms of interaction are an expression of human warmth, courtesy, attention, and consideration for others. Those who have grown up in a similar environment seem to be invested with a natural nobleness of spirit.

Yet Wang Yuming does not have the reticence and certain reserve that nonetheless distinguish most of Henan’s people. He is an extroverted, not diffident, person and has a welcoming nature rather than a self-absorbed one.

The warm affection he showers upon his friends and acquaintances is completely genuine and sincere. It is not spoiled by self-serving calculations or worries about protecting his own interests, jealousy, or envy. Wang Yuming is aware of the Machiavellian rules that dictate interpersonal relationships in all societies and which, given its ancient civilization, are expressed more subtly in China, yet he consciously avoids their pettier implications, preferring to mitigate the captiousness that informs such rules by playing them down through an appeasing toast or hearty laugh. It is not a question of simulated naiveté or even of the ascetic denial of worldly pleasures: Wang Yuming is perfectly able to deal with functionaries and those holding the reins of power, whose language and codes of behaviour he’s aware of, while nonetheless remaining pure in spirit.

And this is demonstrated by the fact that, despite his being close to many highly-placed individuals, his standard of living has always remained unchanged, and his devotion to artistic creation overrides everything else.

Perhaps some will wonder about the reason behind such a detailed portrayal of a “person” in an essay by a self-described “art critic.” I am convinced that a person’s “depth” is a fundamental ingredient in determining the intrinsic value of the works he produces; in Wang Yuming’s case the human qualities he is endowed with inform his work so intensely as to constitute its primary element and guiding assumption.

I met Wang Yuming seven or eight years ago and, through the years, our acquaintance developed, gradually becoming closer, so that only now has “Comrade Wang” decided that the time is ripe to request that I write an essay about his work.

A Bit of Everything

Two years ago I attended a solo show of Wang Yuming’s in Luoyang, entitled Country Folk, City Folk, Landscapes and Flowers . I laughingly asked him, “Why not entitle it A Bit of Everything?”. I think that such a title on one hand reflects Wang Yuming’s extensive interest for his surrounding environment; on the other, it reflects his lack of pretentiousness, his naturally easygoing nature, devoid of all rhetoric and self-presumption.

I have here, lying on my desk, a few small black-and-white catalogues covering his works over the last six years. They are all slim, plain volumes, yet creatively and carefully put together.

As far as I know, like many of his colleagues, Wang Yuming “came into his own” as a photographer beginning in 1989, through his particular interest in documenting Henan’s rural culture, with its many fairs, public celebrations, and folklore, or even just its simple authenticity. Until some time ago, the most well-known and widely recognized role of photography in China was that of documenting or providing a testament of reality. Moreover, given that the dictates The Great Helmsman addressed to intellectuals included that of “experiencing life” , understood as the life led by farmers, or (in smaller measure) workers, it is easy to understand why dozens of amateurs equipped with cameras combed China’s most remote rural areas, and still do so today, in search of rituals, customs, and expressions that have become obsolete in urban areas. I imagine that when he decided to repeatedly take part in the many festivities of the farmers’ Moon Festival, Wang Yuming, who had just been through a number of experiences common to all Chinese persons of his age and social extraction, such as being sent to the countryside to farm the land, subsequently working in a factory and thereafter as a teacher, was animated by a curiosity mixed with a certain sense of familiarity, by an outsider’s viewpoint, which was also simultaneously the sympathetic one of someone participating in what he was witnessing.

Little by little, he abandoned this purely documentary viewpoint, allowing for a more subjective approach and unusual perspectives, less standard cropping, and “unfocussed” effects that were far more evocative than descriptive.

The catalogue Morning & Evening , which won him a prize at the International Festival in Pingyao (I still remember his exultation upon receiving it), is the most obvious expression of a change in the artist’s direction, which now becomes entirely devoted to his personal vision. Immersed in a disquieting darkness and wrapped up in heavy jackets , scarves, and berets, farm men and women of all ages, whose irises appear phosphorescent (thanks to the technical expedient of using the infrared mode), seem to be engaging in arcane rituals. Their expressions almost never appear complete, still, and aware of being immortalized; instead, the photographer has caught them in “transitional” moments, with semi-closed eyes, unsure lips, and half-turned heads. The shots taken from below (by holding the camera against his abdomen, Wang Yuming manages to take many pictures without being noticed), which are very frequent, distort the balance between the whites of the eyes with respect to the irises, making them appear almost frightening. Nonetheless, the photographer is not seeking overly dramatic effects, but rather a feeling of pathos, motion, and intensity, which is akin to that actually felt by those partaking in divinatory rites. Even to an outside observer, the trance-like expressions of these seers, along with the fervour of the beggars and the rites they all seem engaged in, make for a highly enthralling effect. I would say that, instead of limiting himself to offering a kind of “inventory,” or description of a situation, the artist here literally engulfs viewers within it: he emotionally involves them in the situation, pulling them in.

As the man “of passions” he is, Wang Yuming finally steps down from the pedestal of neutrality and “objectivity” upon which photography is often relegated.

I recall a sequence of photographs all taken within a single day, during a popular festivity, and subsequently presented as a short video with a soundtrack (an expedient which is often used in Henan and which I suppose was inspired by the French photographer and curator, Alain Jullien), entitled Lunar Month . Wang Yuming has here chosen to photograph a group of bystanders along the side of a road, as they observe an event, which I suppose is a procession, unfolding before them. One can imagine the photographer following, preceding, or mixing with the train of people, thus capturing the curious, amused, or interested expressions of whole families of spectators. In this case as well, we the viewers, become in our turn members of the crowd and are granted the chance to move and look about.

I also remember a series of photographs taken during the S.A.R.S. emergency, during which Wang visited many provincial villages, which were barred from all “foreigners” by volunteers who stood guard alongside makeshift barriers made of tree trunks and sundry objects, so as to avert the danger posed by close contact which could lead possible infection. The photographer was himself denied access to these areas, and asked that he be allowed to take pictures so as to provide a “testament” of the work being done. He was thus able to photograph a varied array of people who became the improvised guardians of their own and others’ safekeeping; a popular spirit , spontaneous and unofficial in nature, which is conveyed in its genuine innocence and which the viewer almost directly confronts.

City Folk, Country Folk

Upon comparing Wang Yuming’s “country folk” with his “city folk”, what I notice is that, aside from the differences in the gestures, clothing, and environments - in short, the objective elements – they convey a feeling of overcrowding, close contact, and near-promiscuousness in the former case, and one of indifference, detachment, and closure in the latter, which the photographer surely meant to emphasize.

Wang Yuming shows us the eyes and looks – even though they are directed elsewhere – of the “country folk.” He portrays them as attentive and interested in something, as focussed, involved, and curious. They are, for the most part, interacting with each other.

In the images of the city folk, Wang has instead deliberately photographed them from behind or from the side. He underscores their inexpressive faces, as if they were forced to create an inner silence for themselves so as to fend off the overload of external stimulation. While standing at a bus stop, their eyes are lowered as they speak on their cell phones, look at the ground, or clutch a bag. As they ride the bus, their gazes are directed outside so as to avoid meeting those of others. They all seem to be making an effort to limit contact with those around them, who are close enough to exchange glances or words with, and to feel the urgent need to reach a familiar, “safe” environment, different from the one they find themselves in, in which they may relax and feel at ease.

In a mosaic of photographs that Wang Yuming has mounted and paired with a soundtrack, much like a series of slides on a carousel projector, and ironically entitled Picture ID , the photographer has accomplished a further step: from the documentary photographs with which he began his relationship with the camera, to the development of an approach halfway between the documentary and the conceptual. He has photographed the faces of dozens of divinities found in temples or other sacred sites around the countryside, mainly in the Henan and Shanxi (山西) provinces. The painted terracotta or plaster heads, both in good or bad state, constitute a rich gallery of physiognomic expressions. They are, for the most part, not genuine works of art, but rather the sometimes admirable, sometimes-cheap handiwork of artisans. They are extremely colourful: the faces are gold, turquoise, red, ashen…while the eyes range from icily austere slits to astounded spherical apertures. Perhaps it is merely my own interpretation, but I see an entire repertoire of humanity in them. Yet I think that, in light of what has been described above, they more fittingly represent the variegated array of country folk rather than the more predictable, standardized city folk.

Landscapes

Besides being a passionate photographer, Wang Yuming is also acquainted with classical culture; he writes poems and practices traditional ink on paper calligraphy and painting.

Perhaps also because of this, his passionate nature is coupled with a natural predilection for beauty. After the images steeped in pathos of Morning and Evening, and the deliberately direct and simple Avian Flu series, we find several Landscapes whose lunar beauty is achieved through the use of often symmetrical compositions, depths of field, and sometimes vast backgrounds, coupled with the special effect obtained through the infrared mode, which emphasizes the lighter surfaces, making them appear white. These images almost never include people, yet are filled with plentiful, imposing signs of their presence. They consist of powerfully humanized, yet desolate, environments, and it is precisely this paradox, which is one of the reasons for the mesmerizing attraction they emanate. There are chrysanthemum flower beds framed by curtains of weeping willows, coupled with traditional buildings. Or landscapes that have been carved from the land, farmed, and then left to languish in a state of semi-abandonment, along with scenic views of rivers and lakes, or bird’s eye views of industrialized rural areas. It is the sense of suspension they emanate, the still silence, the alienating and unusual whiteness of the foliage, which transform these ordinary environments into epic landscapes. I personally particularly love this series for the timeless, alienating, suspended atmosphere it conveys.

Light

I remember having seen a series of photographs at an exhibition held in Pingyao in 2003, if I’m not mistaken, in which light was the true protagonist amid the whiteness and – especially – blackness of the urban night scenes. This often took the form of illuminated windows upon a dark background, or reflections cast upon the houses facing them, or even the sudden, stark prominence of light, sharply delineated areas upon a blurred surrounding surface – these were rare, suspended images based on the sudden, violent contrast of black against white. I recall that, many years ago, as an art history student, we discussed the expert use of light Caravaggio conceived and his ability to render painting dramatic and full of pathos. Caravaggio to this day remains my favourite painter. Within the world of contemporary Chinese photography, which is still tied to a very “realistic” stance, or its attempts at a conceptual approach, which were rather forced and not at all poetic, I was struck by Wang Yuming’s sensitive, open vision, who – I imagine – during his nightly walks, perhaps returning home from work after a long day, had managed to capture revelatory flashes of light within his city and its daily bustle, and had shown us another vision of reality, made up of black and white strokes and unnaturally sharp lines coupled with blurred areas. His vision is interesting not because it tells a story (I don’t think he’s interested in gossip), but because it holds its own particular beauty which is shaped into abstract compositions that recall the alternation of blacks and whites on the paper of an ink painting rather than the life and volumes of a city at night.

In other words, I think the great talent and special quality of Wang Yuming lies in his ability to capture the beauty, pathos, and humanity present in every corner of his surrounding world. And knowing how to express it with an immediacy that is devoid of all rhetoric and emphasis. It is an expression similar to the one always found in his small, but infinitely lively and passionate eyes.

Monica Dematté

Vigolo Vattaro, 24 August 2008

1957年生于重庆,独立艺术家。

获奖;

2002年 《早晚》获2002年“平遥国际摄影大展阿尔卡特中国优秀摄影画册”三等奖 平遥 山西

2005年 获韩国东江国际摄影节“最佳国外摄影师奖” 东江 韩国

2009年 《圆公园》获爱普生摄影年赛“评委提携大奖” 上海

2013年 《粉彩金莲》 获河南省首届陶瓷艺术展金奖 郑州 河南

2014年 《梅问》系列作品首届中外陶艺家原创新品大赛金奖 景德镇 江西

2015年 《梅问》系列作品2015首届中国瓷画双年展获奖提名 景德镇 江西

展览:

个展

2015年 《这样》 “云水居艺术空间” 洛阳 河南

2015年 《梅问》 “栖霞岭上艺术空间” 杭州 浙江

2014年 《梅问》 “青花国语瓷绘艺术机构” 景德镇 江西

2012年 《青趣》 “左岸瓷绘艺术机构” 洛阳 河南

2012年 《景致》 大理国际摄影会 大理 云南

2007年 《不是》 “咏春画廊” 洛阳 河南

2006年 《乡里人城里人还有景和花》 5+1画廊 洛阳 河南

2005年 《早晚》 韩国东江博物馆 东江 韩国

2003年 《呓语》 平遥国际摄影大展 平遥 山西

群展

2015年 《中灵山》 安心.微艺术空间 洛阳 河南

2015年 《响沙湾》 “春在”影像联欢 洛阳 河南

2014年 《梅问》 “中国首届陶瓷艺术双年展”景德镇 江西

2014年 《梅问》 “百家争鸣陶瓷艺术展” 景德镇 江西

2014年 《粉彩金莲》 “本土与景飘陶瓷艺术展” 北京

2013年 《粉彩金莲》 河南省首届陶瓷艺术展 郑州 河南

2013年 《景致》 全摄影画廊 上海

2011年 《四说新语(瓷绘)》 中国书法院 北京

2010年 《这里》 河南美术馆 郑州 河南

2010年 “Open Frame – New Landscape Photography from China”新加坡YAVUZ Fine Art

2010年 《荷》 周围艺术画廊 上海

2009年 《圆公园》 三尚画廊 北京

2009年 《城·惑》 全摄影画廊 上海

2008年 《景致》 山水文苑艺术中心 北京

2008年 《呓语》 河南美术馆 郑州 河南

2008年 和谐石佛国际艺术展 石佛艺术公社 郑州 河南

2007年 《景致》 BOLZANO 意大利

2006年 《景致》索菲特2006中国当代艺术展 西安 陕西

2006年 《自己的城》 山东青州博物馆 青州 山东

2005年 天安门FOAM博物馆 阿姆斯特丹 荷兰

2004年 火柴MATCHEVENT多媒体国际艺术展 798 北京

2003年 中国人本—纪实在当代 广东美术馆 广州 广东

2003年 “平遥在巴黎 ” 巴黎 法国

出版;

2013年 《王豫明绘瓷》 (本真堂出品)

2013年 《青趣--王豫明绘瓷作品》 (人文艺术出版社)

2011年 《王豫明绘瓷作品集》 (人文艺术出版社)

2011年 《红外摄影作品集》 (中国图书出版社出版社)

2005年 《2005中国当代美术现象考查-影像卷》(2005年)

2004年 《2004中国当代美术现象考查-影像卷》(2004年)

2003年 《阻挡》个人作品集(2003年)

2002年 《早晚》个人作品集(2002年)

收藏;

2010年 《这里》 (三件) 河南美术馆

2010年 《天香(瓷)》(二件) 意大利艺术机构

2008年 《景致》 (二件) 意大利艺术机构

2006年 《呓语》 (四件) 河南博物院

2005年 《早晚》 (二十件) 韩国东江摄影博物馆

2003年 《阻挡》 (一件) 广东美术馆

Wang Yuming

1957 Born in Chongqing.

Current Lives in Luoyang, working as a freelance photographer.

Awards

2015 Plum Blossom Ask, Golden Prize of the First National and International Ceramist New Work Competition, Jingdezhen

2014 Plum Blossom Ask, 2015 Chinese Porcelain Painting Biennale (Nominated)

2013 “Pastel Jinlian”by Henan Province, the first ceramic art exhibition Gold Award

2009 “circle” Epson photography played “Park won awards judges up”

2005 The Best Foreign Photographer at The International Photography Festival of East River, Korea East River, Korea.

2002 Morning and Evening, Pingyao International Photography Festival Al Carter

Third Prize of Chinese Excellent Photo Album "Pingyao Shanxi”

Solo Exhibitions

This Way, ‘Yun Shui’ Art Space, Luoyang, Henan

Plum Blossom Ask,Xixia Lingshang Art Space, Hangzhou, Zhejiang

Plum Blossom Ask, Qinghua Art Institution, Jingdezhen, Jiangxi

2012 Green Interest, Left Bank Porcelain Art Center, Henan

2012 Scenery, Dali international photography of Dali of Yunnan

2007 Is Not, Wing Chun Gallery, Luoyang, Henan

2006 Village City people and scenery and flowers, 5+1 Gallery, Henan, China

2005 Morning and Evening, Dongjiang Museum of Korea, South Korea

2003 Balderdash, Pingyao International Photography Exhibition, Shanxi, China

Group Exhibitions

2015 Zhongling Mountain, Anxin-Micro Art Space, Luoyang, Henan

2015 “Sounding Sand Bay”,”Chun Zai”Image Gala, Luoyang, Henan

2014 Pastel Nasturtiums, Jingdezhen Museum of Contemporary Art, Jiangxi, China

2013 Pastel Nasturtiums, The First Henan Ceramic Art Exhibition, Zhengzhou, Henan, China

2013 Scenery, Quan Photography Gallery, Shanghai

2011 Shi Shuo Xin Yu (porcelain painting), China Calligraphy Institute, Beijing

2010 Here, Henan Art Museum, Zhengzhou, China

2010 Open Frame - New Landscape Photography from China, YAVUZ Fine Art, Singapore

2010 Lotus, Zhou Wei Art Gallery, Shanghai

2009 Circle Park, Three Shang Gallery, Beijing

2009 City·Puzzle, Quan Photography Gallery, Shanghai

2008 Scenery, landscape building of Beijing Art Center

2008 Balderdash, Henan Zhengzhou Art Museum, Henan

2008 Harmonious Buddha Stone Sculpture International Art Exhibition, Zhengzhou, Henan, China

2007 Scenery, BOLZANO Italy

2006 Scenery, Sofit 2006 Chinese Xi'an Contemporary Art Exhibition, Shananxi, China

2006 Shandong City, Qingzhou Shandong Museum, Shandong, China

2005 FOAM Museum of Amsterdam Tiananmen, Holland

2004 MATCH EVENT Multi-media International Art Exhibition, 798 Art District, Beijing

2003 Chinese People - Documentary in the Contemporary China, Art Museum of Guangzhou, Guangdong

2003 Pingyao in Paris, Paris, France

Publications

2013 “Wang Yuming painted porcelain” (true church produced)

2013 “green corner—— Wang Yuming painted porcelain works” (Arts and humanities Press)

2011 “Wang Yuming painted porcelain works” (Arts and humanities Press)

2011 “infrared photographic works” (China Book Publishing Press)

2005 Chinese contemporary art phenomenon study image volume" (2005)

2004 Chinese "contemporary art phenomenon study image volume" (2004)

2003 “barrier” personal collection (2003)

2002 Morning and Evening " personal collection (2002)

Collections

2010 “Here” (three pieces) Henan Art Museum

2010 “Tian Xiang (porcelain)” (two) the Art Institute of Italy

2008 “scenery” (two pieces) the Art Institute of Italy

“balderdash” (four pieces) of Henan Museum

2005 Morning and Evening (Edition of 20), The East River Museum of Photography, Korea.

2003 “barrier” (one piece) Guangdong Museum of Art

眼角镜余

王豫明的图像呓语及其它

杨小彦

本雅明在描述摄影的意义时强调说:大自然对着镜头和眼睛说了各不相同的话。 这句话可以说意味深长。我想,本雅明的意思是,当人们以为摄影的拍摄和眼睛的观看相互重合时,摄影的结果,也就是照片本身,却恰恰证明这种看法是多么的错误。也就是说,我们既不能把照片看成是纯粹的记录,以为它就是构成人类视觉记忆的唯一材料,同时,我们又不能把照片看成是完全主观的产物,以为它无法重建我们的观看历史。一部摄影史已经明白无误地告诉我们,一方面,摄影机在记录自然,另一方面,摄影机还在筛选自然。记录自然的意思是,尽可能让自然呈现出它原本的面貌。而筛选自然的意思则是,让自然呈现出拍摄者可以接受的形式。其实,我们只有在后者的意义上,才把拍摄的结果解释成“作品”。

如果这种看法是可以成立的,我们马上就能获得一个理解摄影史的角度。在如何运用一部机器记录自然物象的外观方面,摄影史提供了无以伦比的例证,这一点无须说明。同时,由于“作品”的“形式”是构成摄影产品的一个视觉前提,所以,我们同样可以把一部摄影史读解成类似“艺术史”那样的历史。正是这个意义上,摄影史才获得了人文的价值,对摄影的解释才具有美学的意义。问题是,一旦这种看法成立,人们往往会用后者来取代前者,也就是把摄影美学化。我想,这大概是摄影界,尤其是中国的摄影界,在长达半个世纪中,对“沙龙摄影”情有独钟的一个原因。

其实,这种现象不独中国才有。翻阅西方摄影史,我们同样看到类似的现象。

理解了上述现象,我觉得就可以理解出现在摄影界的一系列现象。因为,一旦把摄影纳入艺术史描述的范围, 那些原本针对旧有样式进行颠覆与创新就变成了摄影发展的常态。甚至,在一个崇尚创新的氛围中,如果没有一点新东西,被淘汰的命运就可能是无法避免的事情了。

我怀疑王豫明在内心深处也潜藏着这么一丝颠覆精神,否则就无法解释他的几组作品。首先,我看得出来,王豫明是在一个常规的摄影上下文中开始个人探索的。在过去十来年中,这个摄影上下文的主流,可能真的和一场纪实摄影运动有关。许多人,我说的是那些多少对潮流与环境有些敏感的摄影师们,或多或少地放弃了流行中国摄影界的“陈复礼”风,不理会关于“摄影艺术”的一系列呓语般的唠叨,把镜头指向了广大的民间社会。尽管我没有做过什么统计,但我相信,这三十年来,通过摄影师们的镜头所留下来的历史,可能大大超过自摄影传入中国以来的任何一个历史年代。这场纪实摄影运动,可以从王豫明的若干作品中看到某些奇特的影子。

但是,正因为他成长自那个所谓“纪实”的环境中,同时又有些许的颠覆精神,这就决定了他的变异方向无法离开“纪实”。我从他的《呓语》系列中,倒是看出一种无奈与放任。《呓语》拍的是黑夜中的城市,而且拍摄方式是偶发式的。从作品中可以看出作者刻意放弃那种常见的手法,比如寻找一个主题、固定一种拍摄方式、甚至拍摄角度,然后用图像解释之。我猜想王豫明刻意让自己漫无目标地行走,想象自己是一个真正的梦游者,在闲逛中,在甩手中,下意识地去按动快门,好完成一个又一个的瞬间。他舍弃通常的意义,通常的影像效果,通常的影纹层次,通常的让人激动的拍摄对象。我甚至怀疑他不看、或者少看镜头,以减少习惯上的构图积习。他希望自己不是一个拍摄者,而是一个真正的梦游者,然后从梦眼中认识城市。“呓语”是一个很好的关键词,点出王豫明内心所希望的状态。有意思的是,我仍然不认为王豫明是真的“呓语”,他针对一种熟悉的影像传统,一种人们已经习惯的城市形象,而给出自己的答案。问题是,他的答案本身并不是呓语,而是关于“呓语”的影像定义。这就像一个通常意义上的摄影师,他总是从取景框中截取自然。现在,王豫明想颠覆这种“截取”,他的对象与其说是城市,不如说是取景框。于是,他采用了一瞥的姿态,也就是不用全眼,而是用眼角,不留痕迹地把一座城市的潜在形象揭示出来。同样的方式呈现在他另一组命名为《早晚》的人物作品中。这些作品呈现出一种奇特的视觉效果,这种效果,按照作者“技术化”的解释,是用红外线夜拍镜照下来的。作品的人物双眼闪着一点白光,徒然增加了视觉的“幽灵感”,让人惊诧不已。王豫明也发现这种效果非常符合他对“呓语”的想象,不仅塑造出另一种城市的形象,而且还塑造出另一种人的存在。这正是他所切盼的。我以为王豫明运用这种镜头可能带有一定的偶然性,但当他发现“视觉幽灵”真的成为作品事实后,他就无法放弃这种技术了。在他看来,技术在“呓语”中已经消失,剩下的就是真实的灵魂闪现的瞬间。在我看来,这不是镜头人的人物,而是镜头之余的产物。

证明王豫明仍然在纪实的上下文中工作的证据是他的另外两组作品,反映“非典”流行期社会疯狂举动的《阻挡》系列,以及关于民间神坛上各式偶像头部的《标准像》。在《标准像》中,王豫明和观众共同分享一种喜悦,对那些乡人们只能朝拜的、而其实在形象上千奇百怪的偶像作一次深入观察。一般而言,朝拜者是不敢正视那些偶像的,所以他们无法仔细分析制作者在制作偶像时的种种意图,在他们以上中,偶像只有类型的意义,从来没有想象过,这些偶像的“个性”,倒是对人间社会的一种反衬与描述。现在,王豫明把偶像拍下来,而且是以“标准照”的方式,等于通过镜头剥离其崇拜性质,还原其中的世俗成份。同样,当那些给非典弄得神经质的村民们认真地站在村头,阻挡着“真实”的非典进入时,他们也一下子成为象征性的“标准”。其实,所有这一切都具有奇特的象征意味。在一个突然爆发疫情的地方,一个公共医疗系统几近崩溃的国度,对非典的恐惧不仅是实质性的,其实也是象征性的。从这个角度看,那些摆在神坛上的小小的偶像,和庄严站在村头的守卫们,具有一种内在的一致性。王豫明这时不再用他的影像呓语了,因为,在他看来,现实比呓语更呓语化,普通镜头足以表现他的内心震动与惊诧。

本雅明是对的,自然对着镜头和眼睛说了不同的话。本雅明似乎还有一层意思没有完全点明,那就是,自然对着眼睛说的话,除了个人以外,别人听不到(个人又何尝完全听到?)。只有对着镜头说的话,别人不仅听到了,而且还看到了。只是,当别人真的听到、看到这些“话”时,这些“话”,也就是摄影作品,已经离开拍摄者,成为独立的存在,本身就构成了另外一部历史。

王豫明的图像溶到一部比他个人更广大的摄影史中时,他的“呓语”就可能演变成一群人的呓语。

王豫明:热爱生活(节选)

莫妮卡·德玛黛

从他不同时期的作品中,我们可以看出王豫明一点点的放弃了纯粹的记录性视角,转而采用一种更加主观的方式和各种不寻常的角度。他的画面裁剪也不再那么“标准”,他“未对焦”的作品不再具有太多描述性效果,却更加容易唤起观者的共鸣。

他的画册《早晚》中的作品为他赢得了平遥国际摄影节的大奖。这些作品明显表现出他的创作方向的改变,它们采用了完全个人的视角。在这些作品中,不同年龄的农村男女穿着厚厚的棉袄,围着围巾,头戴软帽,沉浸在让人不安的黑暗中。他们的虹膜好像发出一种磷光(这是他采用了红外模式的结果),这些人看起来在参加神秘的仪式。他们的表情几乎都是不完整的,也都处在动态之中,好像并不知道有人在拍照。摄影师记录的是他们“过渡”的时刻:他们的眼睛半开半闭,嘴唇开开合合,头部半扭着。这些从下方拍摄的照片显得节奏很快,扭曲了眼白和虹膜之间的平衡,让他们看起来几乎有些吓人。但是,摄影师并不希望看到一种过分戏剧化的效果,而是力图表现一种悲怆、动感和激烈的感觉,这些感觉和那些占卜仪式的参加者的感觉是相近的。即使在一个外部的观察者看来,这些预言家恍惚的神情、祈祷者狂热的表现和他们沉浸之中的仪式结合在一起,产生了一种扣人心弦的效果。我认为,艺术家在这里并不仅仅局限于“记录”或是描述一个场景,而是让观者感同身受:他让观者把感情投入到了这些场景里,让他们感觉置身其中。

在比较王豫明作品中的“乡里人”和“城里人”时,我注意到他们的姿势、穿着和环境这些客观元素上有着不同。此外,他作品中的“乡里人”有着过度拥挤、近距离接触和杂乱无章的感觉,而“城里人”则体现出漠然、独立和封闭,这些特性也正是摄影师着力刻画的。

王豫明为我们展示了“乡里人”的眼睛和神情——虽然这些人都没有看镜头。在他的作品中,这些人好像在关注一件有意思的事情,对这件事情很好奇,集中精神在研究它。大部分作品中,他们在和其他人互动。而在表现“城里人”的作品中,王豫明故意从背面或侧面进行拍摄。他强调了他们面无表情的脸庞,好像他们在逼迫自己实现一种内心的宁静,以便抵御过多的外部刺激。这些人在公交车站等车的时候,眼睛看着下方的地面,打着手机或是抓着自己的包。他们上了公交之后,眼神都是朝车外看的,因为他们不想和其他人眼神相交。他们好像都在努力减少与周围人的接触。虽然他们之间的距离很近,足可以交流一个眼神或是谈话,他们却感到亟需创造出一种熟悉的、“安全的”环境,这种环境和他们实际处在的环境不同,能让他们感到自在和放松。

王豫明把一系列照片配上了声音,好像是箱式投影机中播放的一张张幻灯片,他为这个系列作品起了《标准照》这个具有讽刺意味的标题。通过这些作品,摄影师实现了进一步的转变:从他刚开始拿起相机拍摄的纪录性影像到一种自己的摄影方式,这种方式介于纪录性和观念性摄影之间。他拍摄了河南和山西等省农村地区寺庙或其它圣地中数十个神像的面庞。这些陶土或灰泥塑成的头像保存的状况各异,但一起组成了多姿多彩的面相集锦。它们大部分其实都不是艺术品,而是匠人打造的工艺品,有些质量让人称赞,有些则看起来就很廉价。这些形象极其色彩丰富:他们的脸有金色、青绿色、红色和灰色等等,而他们的眼睛也各式各样,有的仅仅是冷冰冰的一道裂缝,而有的则是让人吃惊的球形构造。可能这只是我自己的理解,但是我从他们中看到了人生百态。我认为,基于到我前面所描述的内容,他们代表的应该是各式各样的乡里人,而不是更加循规蹈矩、步调一致的城里人。

王豫明不仅是一名充满激情的摄影师,还对于古典文化十分熟悉。他会做诗,也会时常写写书法,画画水墨。可能是由于这个原因,他的热情的个性中还包含着对于美的自然的偏爱。在他创作了充满悲怆的“早晚”系列和简洁明快的禽流感作品系列之后,他拍摄了一组“景致”的照片,它们异样的美体现在不对称的构图、景深和时常出现的广阔的背景之中。此外他还采用了红外模式,突出了光亮的表面,让它们看起来像是白色的。这些图像中几乎没有人出现,但是却充满了各种让人印象深刻的人类活动的痕迹。它们展现了虽然被人类改造过,但看上去很荒凉的各种环境。而正是这种看似矛盾的特质让这些作品散发着让人入迷的吸引力。我们可以在图片中看到被垂柳围绕的菊花花床,周围还能见到古典风格的建筑。我们也能看到土地在被开垦耕作之后,处于一种半废弃的状态。这些作品中还有一些河流湖泊的景色或是大规模开垦的农村地区的鸟瞰图。它们所表达的悬停感、无声的寂静和呈现出让人感到疏远和不寻常的白色的各种植物将这些普通的环境转变成了宏大的风景图。我个人尤其喜欢这个系列的作品,钟爱它们营造出的永恒、疏远和悬停的氛围。

我记得2003年在平遥的一个展览中看过一个系列的照片。如果我没记错的话,这些照片真正的主角是城市夜景中的白色和特别突出的黑色。有的照片表现的是黑色背景中明亮的窗户,或面对这些窗户的房屋上反射的灯光,抑或是在模糊的背景中突如其来的、十分明亮的灯光——这些照片基于突然的、巨大的黑白反差,产生了少见的悬停的图像。在许多年前,我还是一个学艺术史的学生,我们讨论过卡拉瓦乔(Caravaggio)对于光线的高超运用,他能够将绘画变得充满戏剧效果和悲怆感。卡拉瓦乔至今仍然是我最欣赏的画家。在当今中国的摄影界,很多人还是处于一种记录“现实”的状态,或是虽然做了一些观念摄影的尝试,但是作品看起来既勉强,又完全没有诗意。因此,我对于王豫明敏感、开放的视野深感讶异。我想,他可能是在晚上下班回家的路上,捕捉到了自己城市喧嚣中充满启发的灯光,给我们展示了另一种现实,那里充满了黑色和白色的笔触,不自然的尖锐线条和模糊的区域。他的眼界有趣的原因不在于这些作品讲述了一个故事(我估计他对嚼舌根没兴趣),而在于它自身具有一种独特的美,这些美体现在抽象的构图中,让我们想起了水墨画中黑白的交替,而不是一个城市的夜生活。

我认为王豫明的禀赋和特质主要在于他能够捕捉周围世界中的美丽、悲怆和人性。他知道如何将这些直接表现出来,而不会采用很多浮夸和强调的手法。这是在他那双虽然不大,但是非常有活力和热情的眼中所看到的世界的表现。

Cornes of ‘Eyes’, Edges of ‘Lens’

-- Wang Yuming’s photographic dream-talk and beyond

By Yang Xiaoyan

When Walter Benjamin described the meaning of photography, he stated, that nature told different words in front of our eyes and lenses. When I interpreted this notion I think, that his initial meaning was to point out how the photographs, as results of shooting, cannot prove the believe that “we see what we capture”; that is to say, cameras document nature, but it also filter nature as well. Hence the two extreme commentaries on photography, which is, either the absolutely objective documenting or subjectively personal, are wrong from both sides. Photographs are not (and will not be) the only surviving visual resource of mankind, but it has its significance. It could slightly change the way we perceive our surroundings. A photographer shoots nature. A photographer also selectively shoots nature, which means the photographs are the evidence of the filtering process. It is the latter one what can be categorized as “artwork”.

A new perspective on the history of photography immediately will be established if the above are agreed.There is no need to particularly illuminate the utilizing machines to document the materialized world, as there have been so many examples; meanwhile, the “artwork” and its “form” are the prerequisites of any photographic series, which is verisimilar to the visual prerequisites of fine art, we can refer the history of photography to the history of art. As a result of the association, the history of photography, then gains values in a matter of humanism and aesthetics. However, once this opinion is accepted by the majority, a potential danger is to erase the former with the latter, which is only to understand the photography’s history in an aesthetic manner, and that explains why photographers, especially photographers in China are obsessed of the so-called salon photography.

It’s absolutely not a phenomenon occurs only in China. The western photography shares the similar situation.

An understanding of the phenomenon above will lead us to be able to thoroughly seeing through this occurrence. Because once photography is put in the realm of art history, so easily the Avant-garde turns to be normal, and in an era that innovation is highly worshiped, the fate for the normality is inevitable elimination.

I fancy that WANG Yuming subconsciously adopted the Avant-garde concept, or at least partially; otherwise it falls into an absurdity in the attempt to interpret some of his series. Yuming started his individual debut on photography with an ordinary context. The passing ten years saw the mainstream of this context, and in my opinion, it has to do with the documentary photography movement. Many, I mean those of alert to trends and political climates, had more or less abandoned the very dominated domestic “CHAN Fooklai” trend, had ignored the chatter about “the art of photography”, and switched their focus to the lower classes, which are massively existent. I assume, even without supportive statistics, that the eventful moments taken by photographers from this three decades is rapidly transcending any other eras in China’s history. Some of Yuming’s photograph series singularly reflected this movement of documentary photography.

He immersed in this movement and he is one of the Avant-garde. This combination fundamentally determines the documentary elements in his art, despite his abstract approach. Take his Murmur series as an example, the subject is cities at night and his process is rather spontaneous. Instead of the mainstream shooting method, which is to firstly is settling down the subject and the settings, then elucidating with following photographs, he let himself walking around without a clean idea. Or to be precise, he became a somnambulist, who captures the moments by clicking the shutter subconsciously. Going against the majority’s taste, he abandoned normal meaning, normal effects, normal textures and all normal exciting objects; he may not even look at his viewfinder in order to against any kind of shooting habits. “Murmuring” is a perfect word that frames the state he expected, though I don’t think he wasn’t aware of this activity; when facing the accustomed traditions on photography and a large amount of photographs on city view, his action was seemingly like visual nonsense yet his answer was the clear definition of murmuring and its imagery.

In his Morning and Evening series, the infrared ray effects gleam phosphorescence in the villagers’ eyes, of what dramatically creates a phantom-like tension. It is terrifying for the audiences, but he found, and very much pleased with this special effect, for not only it fits the imagery of “murmur”, but also it creates a city and people in another dimension. He was longing this imagery, and once he accidently discovered the infrared ray effect and its potentials as “visualized phantoms”, he never loses his interest of this technique. For him, craftsmanship has vanished in those attempts of visualizing murmurs; what are essential are the shimming moments of those real souls. For me, those who appear in his lenses are just byproducts from his viewfinders; those are definitely not portraits. Compare to normal photographers who will “cut off” nature through their viewfinders, Yuming’s approach is to cut off this “cut off” action by switching his focus to his viewfinders.

The defense series and the official portrait series prove the documentary photography influence of him. The former captured the insanity occurs in a village during SARS period while the latter captured profiles of idols on many altars. People worship those idols without looking at them; the awe they hold preventing them from questioning the craftsmen’s intention. For them, those deified statues are stereotypes; they never really imagine the varied characteristics finalized by craftsmen; not to mention the idea of those idols as foils of our society. WANG Yuming closely observed those idols and frankly captured their deified yet uncanny characters. By using the form of the official portrait, he separated their halos and extracted their earthliness. He also subtly captured the villagers being overwhelmed and their desperate yet illusory defense of the real happening SARS. Their activities became a certain symbol and standard stereotype, which create a queer symbolic implication to the whole series. It is not to say that the substance and the symbolization are completely detached from each other; in another angle, in where a domestic epidemic was infected and it happens to be in the nation where medical system was destructed, the solemn defenders of SARS and the aloof idol co-possess the inherent similarities.

Until reaching this point WANG Yuming stopped using his signature visual murmur; because for him, the reality is more like nonsense than any murmur, he intended to create; consequently any distinctive lenses would no less capture his astonishments. When WANG Yuming’s photographs dissolve into a massive panorama of photography, he murmurs, I guess, will be a group, or a whole salon’s murmur.

Walter Benjamin was right, nature told different words in front of our eyes and lenses, yet he didn’t expound what a personal experience it is. Let us recall the moment of shooting, actually no anyone else can hear what nature tells the photographer; only the photographs, of which gained their independent existence, convey the words from nature to the audiences. They made their own history.

Wang Yuming: In Love with Life

I have often seen Wang Yuming laugh, toast his glass, sing, and jestingly incite others to merrymaking. Sometimes I’ve caught him in a sad and serious mood. His cheerfulness is certainly laden with optimism and great inner strength, yet it is also imbued with the melancholy and resignation of those who know that the human condition can be difficult and full of hardships, and that it is wiser to face even its less pleasurable aspects by experiencing them intensely, like gulping down a glass of some sour liquid rather than feigning a superficial indifference or convenient detachment.

“Comrade Wang,” as I teasingly like to refer to him, recalling a time in which the term was ubiquitously used, and was invested with a value that went beyond pure form, etiquette, or custom, is a person who would give everything for his friends, who lives a very intense social life, and is always ready to consider the needs of others before his own. At times this attitude turns against him, even affecting his physical well-being, while at others his warm-hearted, generous nature must endure the blows of a fast-paced, busily industrious daily routine and his lack of regard for his physical health.

Wang Yuming was born in Chongqing of Sichuanese father and later moved to Henan, an “ancient” province, from which I think he has absorbed a few deeply traditional aspects. Henan is a region I especially love, partly because of its quite numerous extant examples of Han art, of which I am an enthusiast. The tumuli scattered throughout the countryside, which mark where the tombs of the nobility once stood, seem to conjure up the voices of a great civilization. This is a province whose people still live according to modes of behaviour that are based on deep mutual respect. When such modes do not result in the mere empty or hypocritical enactment of the rules of etiquette, which can happen anywhere, such forms of interaction are an expression of human warmth, courtesy, attention, and consideration for others. Those who have grown up in a similar environment seem to be invested with a natural nobleness of spirit.

Yet Wang Yuming does not have the reticence and certain reserve that nonetheless distinguish most of Henan’s people. He is an extroverted, not diffident, person and has a welcoming nature rather than a self-absorbed one.

The warm affection he showers upon his friends and acquaintances is completely genuine and sincere. It is not spoiled by self-serving calculations or worries about protecting his own interests, jealousy, or envy. Wang Yuming is aware of the Machiavellian rules that dictate interpersonal relationships in all societies and which, given its ancient civilization, are expressed more subtly in China, yet he consciously avoids their pettier implications, preferring to mitigate the captiousness that informs such rules by playing them down through an appeasing toast or hearty laugh. It is not a question of simulated naiveté or even of the ascetic denial of worldly pleasures: Wang Yuming is perfectly able to deal with functionaries and those holding the reins of power, whose language and codes of behaviour he’s aware of, while nonetheless remaining pure in spirit.

And this is demonstrated by the fact that, despite his being close to many highly-placed individuals, his standard of living has always remained unchanged, and his devotion to artistic creation overrides everything else.

Perhaps some will wonder about the reason behind such a detailed portrayal of a “person” in an essay by a self-described “art critic.” I am convinced that a person’s “depth” is a fundamental ingredient in determining the intrinsic value of the works he produces; in Wang Yuming’s case the human qualities he is endowed with inform his work so intensely as to constitute its primary element and guiding assumption.

I met Wang Yuming seven or eight years ago and, through the years, our acquaintance developed, gradually becoming closer, so that only now has “Comrade Wang” decided that the time is ripe to request that I write an essay about his work.

A Bit of Everything

Two years ago I attended a solo show of Wang Yuming’s in Luoyang, entitled Country Folk, City Folk, Landscapes and Flowers . I laughingly asked him, “Why not entitle it A Bit of Everything?”. I think that such a title on one hand reflects Wang Yuming’s extensive interest for his surrounding environment; on the other, it reflects his lack of pretentiousness, his naturally easygoing nature, devoid of all rhetoric and self-presumption.

I have here, lying on my desk, a few small black-and-white catalogues covering his works over the last six years. They are all slim, plain volumes, yet creatively and carefully put together.

As far as I know, like many of his colleagues, Wang Yuming “came into his own” as a photographer beginning in 1989, through his particular interest in documenting Henan’s rural culture, with its many fairs, public celebrations, and folklore, or even just its simple authenticity. Until some time ago, the most well-known and widely recognized role of photography in China was that of documenting or providing a testament of reality. Moreover, given that the dictates The Great Helmsman addressed to intellectuals included that of “experiencing life” , understood as the life led by farmers, or (in smaller measure) workers, it is easy to understand why dozens of amateurs equipped with cameras combed China’s most remote rural areas, and still do so today, in search of rituals, customs, and expressions that have become obsolete in urban areas. I imagine that when he decided to repeatedly take part in the many festivities of the farmers’ Moon Festival, Wang Yuming, who had just been through a number of experiences common to all Chinese persons of his age and social extraction, such as being sent to the countryside to farm the land, subsequently working in a factory and thereafter as a teacher, was animated by a curiosity mixed with a certain sense of familiarity, by an outsider’s viewpoint, which was also simultaneously the sympathetic one of someone participating in what he was witnessing.

Little by little, he abandoned this purely documentary viewpoint, allowing for a more subjective approach and unusual perspectives, less standard cropping, and “unfocussed” effects that were far more evocative than descriptive.

The catalogue Morning & Evening , which won him a prize at the International Festival in Pingyao (I still remember his exultation upon receiving it), is the most obvious expression of a change in the artist’s direction, which now becomes entirely devoted to his personal vision. Immersed in a disquieting darkness and wrapped up in heavy jackets , scarves, and berets, farm men and women of all ages, whose irises appear phosphorescent (thanks to the technical expedient of using the infrared mode), seem to be engaging in arcane rituals. Their expressions almost never appear complete, still, and aware of being immortalized; instead, the photographer has caught them in “transitional” moments, with semi-closed eyes, unsure lips, and half-turned heads. The shots taken from below (by holding the camera against his abdomen, Wang Yuming manages to take many pictures without being noticed), which are very frequent, distort the balance between the whites of the eyes with respect to the irises, making them appear almost frightening. Nonetheless, the photographer is not seeking overly dramatic effects, but rather a feeling of pathos, motion, and intensity, which is akin to that actually felt by those partaking in divinatory rites. Even to an outside observer, the trance-like expressions of these seers, along with the fervour of the beggars and the rites they all seem engaged in, make for a highly enthralling effect. I would say that, instead of limiting himself to offering a kind of “inventory,” or description of a situation, the artist here literally engulfs viewers within it: he emotionally involves them in the situation, pulling them in.

As the man “of passions” he is, Wang Yuming finally steps down from the pedestal of neutrality and “objectivity” upon which photography is often relegated.

I recall a sequence of photographs all taken within a single day, during a popular festivity, and subsequently presented as a short video with a soundtrack (an expedient which is often used in Henan and which I suppose was inspired by the French photographer and curator, Alain Jullien), entitled Lunar Month . Wang Yuming has here chosen to photograph a group of bystanders along the side of a road, as they observe an event, which I suppose is a procession, unfolding before them. One can imagine the photographer following, preceding, or mixing with the train of people, thus capturing the curious, amused, or interested expressions of whole families of spectators. In this case as well, we the viewers, become in our turn members of the crowd and are granted the chance to move and look about.

I also remember a series of photographs taken during the S.A.R.S. emergency, during which Wang visited many provincial villages, which were barred from all “foreigners” by volunteers who stood guard alongside makeshift barriers made of tree trunks and sundry objects, so as to avert the danger posed by close contact which could lead possible infection. The photographer was himself denied access to these areas, and asked that he be allowed to take pictures so as to provide a “testament” of the work being done. He was thus able to photograph a varied array of people who became the improvised guardians of their own and others’ safekeeping; a popular spirit , spontaneous and unofficial in nature, which is conveyed in its genuine innocence and which the viewer almost directly confronts.

City Folk, Country Folk

Upon comparing Wang Yuming’s “country folk” with his “city folk”, what I notice is that, aside from the differences in the gestures, clothing, and environments - in short, the objective elements – they convey a feeling of overcrowding, close contact, and near-promiscuousness in the former case, and one of indifference, detachment, and closure in the latter, which the photographer surely meant to emphasize.

Wang Yuming shows us the eyes and looks – even though they are directed elsewhere – of the “country folk.” He portrays them as attentive and interested in something, as focussed, involved, and curious. They are, for the most part, interacting with each other.

In the images of the city folk, Wang has instead deliberately photographed them from behind or from the side. He underscores their inexpressive faces, as if they were forced to create an inner silence for themselves so as to fend off the overload of external stimulation. While standing at a bus stop, their eyes are lowered as they speak on their cell phones, look at the ground, or clutch a bag. As they ride the bus, their gazes are directed outside so as to avoid meeting those of others. They all seem to be making an effort to limit contact with those around them, who are close enough to exchange glances or words with, and to feel the urgent need to reach a familiar, “safe” environment, different from the one they find themselves in, in which they may relax and feel at ease.

In a mosaic of photographs that Wang Yuming has mounted and paired with a soundtrack, much like a series of slides on a carousel projector, and ironically entitled Picture ID , the photographer has accomplished a further step: from the documentary photographs with which he began his relationship with the camera, to the development of an approach halfway between the documentary and the conceptual. He has photographed the faces of dozens of divinities found in temples or other sacred sites around the countryside, mainly in the Henan and Shanxi (山西) provinces. The painted terracotta or plaster heads, both in good or bad state, constitute a rich gallery of physiognomic expressions. They are, for the most part, not genuine works of art, but rather the sometimes admirable, sometimes-cheap handiwork of artisans. They are extremely colourful: the faces are gold, turquoise, red, ashen…while the eyes range from icily austere slits to astounded spherical apertures. Perhaps it is merely my own interpretation, but I see an entire repertoire of humanity in them. Yet I think that, in light of what has been described above, they more fittingly represent the variegated array of country folk rather than the more predictable, standardized city folk.

Landscapes

Besides being a passionate photographer, Wang Yuming is also acquainted with classical culture; he writes poems and practices traditional ink on paper calligraphy and painting.

Perhaps also because of this, his passionate nature is coupled with a natural predilection for beauty. After the images steeped in pathos of Morning and Evening, and the deliberately direct and simple Avian Flu series, we find several Landscapes whose lunar beauty is achieved through the use of often symmetrical compositions, depths of field, and sometimes vast backgrounds, coupled with the special effect obtained through the infrared mode, which emphasizes the lighter surfaces, making them appear white. These images almost never include people, yet are filled with plentiful, imposing signs of their presence. They consist of powerfully humanized, yet desolate, environments, and it is precisely this paradox, which is one of the reasons for the mesmerizing attraction they emanate. There are chrysanthemum flower beds framed by curtains of weeping willows, coupled with traditional buildings. Or landscapes that have been carved from the land, farmed, and then left to languish in a state of semi-abandonment, along with scenic views of rivers and lakes, or bird’s eye views of industrialized rural areas. It is the sense of suspension they emanate, the still silence, the alienating and unusual whiteness of the foliage, which transform these ordinary environments into epic landscapes. I personally particularly love this series for the timeless, alienating, suspended atmosphere it conveys.

Light

I remember having seen a series of photographs at an exhibition held in Pingyao in 2003, if I’m not mistaken, in which light was the true protagonist amid the whiteness and – especially – blackness of the urban night scenes. This often took the form of illuminated windows upon a dark background, or reflections cast upon the houses facing them, or even the sudden, stark prominence of light, sharply delineated areas upon a blurred surrounding surface – these were rare, suspended images based on the sudden, violent contrast of black against white. I recall that, many years ago, as an art history student, we discussed the expert use of light Caravaggio conceived and his ability to render painting dramatic and full of pathos. Caravaggio to this day remains my favourite painter. Within the world of contemporary Chinese photography, which is still tied to a very “realistic” stance, or its attempts at a conceptual approach, which were rather forced and not at all poetic, I was struck by Wang Yuming’s sensitive, open vision, who – I imagine – during his nightly walks, perhaps returning home from work after a long day, had managed to capture revelatory flashes of light within his city and its daily bustle, and had shown us another vision of reality, made up of black and white strokes and unnaturally sharp lines coupled with blurred areas. His vision is interesting not because it tells a story (I don’t think he’s interested in gossip), but because it holds its own particular beauty which is shaped into abstract compositions that recall the alternation of blacks and whites on the paper of an ink painting rather than the life and volumes of a city at night.

In other words, I think the great talent and special quality of Wang Yuming lies in his ability to capture the beauty, pathos, and humanity present in every corner of his surrounding world. And knowing how to express it with an immediacy that is devoid of all rhetoric and emphasis. It is an expression similar to the one always found in his small, but infinitely lively and passionate eyes.

Monica Dematté

Vigolo Vattaro, 24 August 2008

豫公网安备 41019602002106号

豫公网安备 41019602002106号