张惠宾

1963年出生,1993年开始摄影创作。

曾任《中国摄影报》图片编辑,《中国摄影家》杂志专题部主任、执行副主编、编委,中国摄影画廊学术主持。

作品有《诗中原》、《夜北京》及《中原猪娃市场》、《鱼市》、《麦捞》等。

When reading Poetizing The Central Plain, it has been a wonderful journey. This was not only because that I’m interested in picture itself, but also the scene and characters it provide, more importantly, I saw some even more precious qualities within the images: Solid but not rhetoric, direct but not vulgar, balance but not weird, humor but not sarcastic.

Photography is a complex whole, not a judge can easily claim that its effective role in the whole; Even just "documentary photography", the use of this concept also has traditionally been more ambiguity. In fact, the Chinese concept theory on often in critical discourse expression of chaos, the causes and the Chinese way of groups of words, expression of western translation, inertia, lack of logic and so on. As the saying goes, "you know", also can press the table. But the concept of clear and often seem to be very necessary, rather than excess of gossip.

Simply, I tend to establish a large category can be called "social photography", and "documentary photography" as one of the child categories. The former is big concepts, with an overall principle; the latter is a smaller concept, has its own unique general principles. Therefore, regardless of the interpretation of documentary photographic works from a social position analysis, or from the perspective of aesthetic form, both need to be careful—Or, when the so-called art criticism words fail. If, considers “Poetizing The Central Plain” as specimens to distinguish the concept of documentary photography, then how to evaluate its value?

First of all, I take in the work “Poetizing The Central Plain” as an essential documentary photography text. For me, which mean, will result in a double deviation - that is, the timeliness (not "time") and eventness (not "events"). This dual deviation distinguishes it from other "social photography" such as news photography, reportage photography, etc. In another word, documentary photography, whether it's timeliness or eventness, has built-in ideological discourse and specific speaking position, which lies in a complete reconstruction, to become a part of the society narrative.

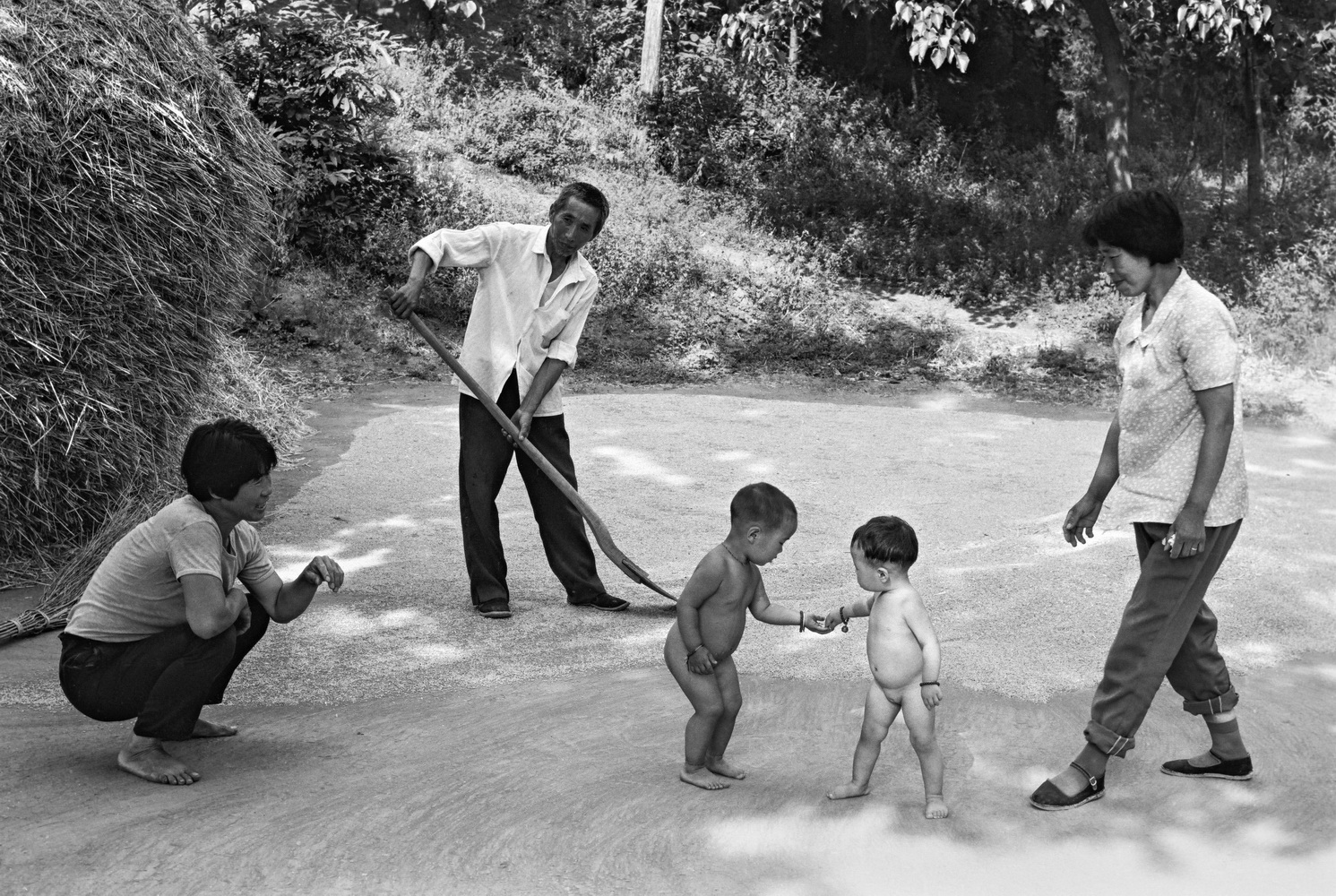

Poetizing The Central Plain embodies in a simple chemical and micro social sampling, no default, no deliberate intent, to give up existed and given rational judgment. Provided it with the photographer. As "my opinion" of the photographer, only provides a vivid visual slice of the Central Plain rural life in China. It not actively construct a grand and passionate preaching, and thus have a more objective and direct reality. Because it is not deliberately creating visual impacts and emotional stimuli; thus to have fresh characters and scenes, and reflects a kindness concerns of intellectuals.

Secondary, and further, “Poetizing The Central Plain” uses a strong sense of presence and rich visualization to provide a real way of seeing for documentary photography.

The Poetizing the Central Plain is taken from an observer's perspective during the film camera era. Certainly, Zhang Huibin must waste a lot more negatives before getting to here. In fact, to carefully screen out excellent negatives is a required course for all photographers.

Those photos in the album of "Poetizing The Central Plain" that he screens out from the numbers of negatives, are retained without cutting shape. I emphasize this point, not to follow the so-called composition method (which is in front of me, using the word "frame" and not "composition". The former is in terms of the results, and is a noun; the latter is a technique, is a verb), but because I am quite the value of intuitively controlling the core valid information in the image of the documentary photograph. It is at this point, the existence of negatives I think is particularly important.

Zhang Huibin utilizes the camera 135 with 50mm lens, I'll discuss further about it in the article." Here, first of all, as we known, the difficulty of using a prime lens lies in its completely fixed frame, position decides the frame, it determines the content of the image "one-off", the visual information that you want to convey is instantly sealed, theoretically no adding or deleting.

Based on my experience of shooting, any photos shot by a short-focus fixed lens makes the picture more attractive. I have no doubt about that!

Such works, the main idea are clear, but not stressed, not overly highlighted, you would not ignore what the camera focusing, but be able to look at other details and every corner. This is what I call "points are all in the field". This is one thing that we often neglect, but I believe that this is exactly the visual genius that documentary photography offers, which is completely more than what we can get at the scene by directly watching through our naked eye.

Based on experience level, there is a natural focus point in every single moment of "eye view", (which is actually a relatively small focus point), at its disposal, we tend to "blind" out all other information in the picture. In this sense, what we captured at a certain moment indeed creates possibilities for people “revisit" again and again. And more importantly, in face, excellent documentary photographers are not only filling in visual blanks for those people who are absent from the story, but also make both people in the image and the outside viewer discover new things. Instead, it is that telephoto lens continues our visual habit, rather than standard lens fit our viewing angle.

“Poetizing The Central Plains” shoots in black and white film, when speaking of film, I could not help to say a few more words. In the study of documentary photography, it seems unlikely that someone dives deep into both film and digital shooting techniques such as the way of shooting, prejudgment of effect, timing, and the difference psychologically of creation. Additionally, even in the field of literature study, few people dive deep into the study of how writing materials (handwriting or electronic writing) would affect writers’ writing ideas. In my opinion, this is a quiet field of study, and also could be an important point of view in aesthetic criticism.

Specifically, in documentary photography, the significance of negatives to a photographer is like a manuscript to an author, is a valuable "trace". Compared to digital, somehow lead to different considerations on shooting, and, determine the shooting behavior from its initial perspective. This is an area need to be focused when studying documentary photography works. Based on the point of view, Zhang Huibin’s photographic work“Poetizing The Central Plains” is done very well. As you can see, he is very familiar with the shooting area's life, and has a continuous excitement at the site, but still maintains a moderate attitude towards shooting. The photographs are quite attractive, not only because of unexpected details, but also because of its sensitive to “focus points” while concerning about the whole scene; which make us constantly discover new information and meaning.

Zhang Huibin always uses a 50 mm prime lens (called “standard lens” in the following paragraphs) for his photographs. It is a not common “behavior” in the documentary photography world; and critics have different opinions about this habit. In my opinion, his choice of “standard lens” is simply a result of his poor personal financial condition at the beginning period of his photographic career. In those days, many people started their photography career with a “standard lens”, and called it the “first love”. It is quite different from now. Now, a common choice for beginner photographers is generally a 28-85mm or 24-105mm lens. People have their own opinion on the trendy phenomenon, some believe that it probably because of the worship-like kind of imitation; the others believe that it is only an inevitable process during the popularization of photography is China. No matter what, there are indeed some excellent, ““standard lens” documentary photographer in China.

Admittedly, the camera lens is gradually changing our way of seeing the world. It greatly expands people's creativity; but from visual "imitation", it inevitably changes our vision in turn. In terms of documentary photography, we have to maximally keep our cautiousness towards it. Because in my opinion, the visual view and presence, is ultimately an expression of one's attitude and position. Not include power and changes in color reduction degrees, there are mainly two different “changes” in two aspects, they might looks be like simple, but if a little reflection will be found in essence.

Back to the work series “Poetizing The Central Plains”, I thought the best example of using “standard lens” can be Zhang Huibin. From his work, it is not hard to notice that his excellent mastery over the specific type of camera lens, and posses a comprehensive understanding of it. His image reflects visual features only could be produced by a “standard lens”, including the observing distance and the feeling of space. However, this kind of distance and space is not simply a result of physical measurement, but also a result of art style judgement. The quality of such result depends on the inherent character of documentary photography.

What’s Interesting, Zhang Huibin works always make me constantly look for his position when taking the photo. Generally, we don’t look at a work caring about this question. But think further, we should not give up in the meaning of this judgement brings to us. This is a study of inside relationship of a documentary photography work; coincidentally, it is based on familiarity of using a 50 mm lens.

Take the picture “Monologue Storyteller" (1994) as an example, the storyteller get himself immersed in his own ecstasy, and totally ignores the existence of the camera; the audience downstage is completely attracted by the storyteller's facial expression and voice, they are not distracted by the involvement of the photographer (shutter sounds may be submerged, just only this "one time" click sound making people look at the camera). This position is slightly remote, but the technique is appropriate, as when slight move to the right, it could make the storytellers overlap with the tree behind him. Here it seems to be the "fourth wall” in a traditional drama show stage. In the scene, storytellers is an actress, others are the audience; In terms of the photographic image, everyone is an actor, we are the audience. In a camera mode, Zhang Huibin is in presence, is a member of the audience too; for the finished photo work, Zhang Huibin is “missing", but he is not missing in fact. The paradox itself seems interesting to me. This photograph has the every typical feature that a “standard lens” could produce— appropriate presence, no disturbance, not insulated, but has a natural restoration of the actual scene.

Most of Zhang Huibin’s photographs reflect what I call “appropriate presence", is a kind of modest integration with a scene. Only in this way, naturally, his work gives us a reliable way of seeing. Just like we're following him, and we "share" one subjective perspective walking across on the site. In the central plains, Zhang Huibin is not a tourist, but someone who “returns" home, and becomes a sociological observer. But he can make us become a tourist, that can blend of tourists, in turn, also can make us become the observer.

I can imagine, when Zhang Huibin appears in villages carrying his camera, he is not “invading”, not a outsider at all.

“Standard lens" has a unique power. My attitude towards photography was mentioned in the first section, and in the second section I discussed an emphasis on effective information, here I am emphasizing the important of “presence”, which is a strong power that attributes to most scenarios in photography.

Zhang Huibin’s presence is clearly identifiable. For documentary photography, presence is critical.

(Jin Ning, Photography critic Deputy Editor of “Art Research”)

1963年出生,1993年开始摄影创作。

曾任《中国摄影报》图片编辑,《中国摄影家》杂志专题部主任、执行副主编、编委,中国摄影画廊学术主持。

作品有《诗中原》、《夜北京》及《中原猪娃市场》、《鱼市》、《麦捞》等。

Zhang Huibin

Born in 1963, started photography career in 1993.

Served as the photo editor at China Photography, Managing editor and deputy editor at Chinese Photographer, Academic advisor at China Photo Gallery.

Works include “Poetry for the Central China”, “”Night Beijing”, “Pig Market in Central China”, “Fish Market”, etc.

摄影家张惠宾和他的《诗中原》

摄影家张惠宾和他的《诗中原》

金宁

阅读《诗中原》,在我始终是一个愉快的过程。这不仅是因为我感兴趣于画面本身提供的场景和人物情状,重要的是,从中看到了在今天愈发显得珍贵的影像品质:扎实而不虚夸,直接而不粗俗,平正而不怪异,幽默而不嘲讽。

摄影是一个复杂的整体,没有一种判断可以轻易宣称其有效作用于这个整体;即便仅仅是“纪实摄影”,对这个概念的使用也历来歧义多出。事实上,汉语中的理论批评话语时常困扰于概念表述的混乱,其成因与汉语的组词方式、西文转译、表述惯性、逻辑缺乏等等有关。俗话说“你懂的”,也只能按下不表。但概念的清理又时常显得非常必要,而不是多余的闲话。

简单说,我倾向于确立一种暂且可以称之为“社会摄影”的大类别,而把“纪实摄影”看做其中的一个子类别。前者是大概念,有统摄性的总体原则;后者是小概念,有其自身独具的一般原则。由此观之,无论从内容出发的社会立场分析,还是就形式而言的美学视角分析,对纪实摄影作品的解读都需谨慎——或者,会涉及社会效用的争执和目的性的纠缠,并稍不留心就被空泛的意义绑架;又或者,所谓艺术的批评话语往往失效,变成人云亦云的新八股。那么,若把《诗中原》视为这个概念区分中的纪实摄影的标本,又该如何看待其价值?

首先,我把《诗中原》视为一种本质意义上的纪实摄影文本。

在我看来,所谓本质意义上的纪实摄影,必然会表现出双重的背离——即对时间性(不是“时间”)与事件性(不是“事件”)的背离。它既不在时间性线索中强调历史演进与所谓进步正义,也不在事件性叙述中再现问题意识与价值评判。这种双重背离正是其区别于“社会摄影”中的其他子类别(比如新闻摄影、报道摄影)的根本所在。深一步讲,非本质的纪实摄影,无论时间性还是事件性的表达,其中都内置了意识形态话语和传播策略并强调特定的立场,它必须凭借完整的意义建构,才能成为社会整体叙事中的一环。

《诗中原》体现为一种朴素化与微观化的社会采样,没有预设的、刻意的观念意图(但并非没有观念),放弃先在的、被赋予的理性判断(也绝非缺乏理性)。它以摄影家之“我见”,提供的只是有关中原农村生活的生动的视觉切片。它不主动去建构宏大意义与激情说教,因而有着更加客观与直接的真实。它不刻意地制造视觉冲击和情绪刺激,因而人物和场面鲜活有趣,体现出亲切的平视的视角和知识分子发乎本能的乡土关切。从这个意义上也可以说,张惠宾属于那类立足于纪实摄影原点的摄影家,在纪实摄影中比较具有“原教旨”色彩。可以肯定的是,如他这类作品,具有更持久的观看价值,也更具备社会学意义上的认识价值。

其次,但同样重要的是,《诗中原》以强烈的现场感与丰富的视觉性,提供了真正属于纪实摄影的观看。

《诗中原》作为个体视角的乡村观察,拍摄于距今不算太远的胶片时代。可以肯定张惠宾扔掉的片子不在少数,追究片比、研究废片在我看来不仅没有意义,而且近乎学术八卦。事实上,对冲洗出来的底片进行仔细筛选,同样是摄影人必修的功课。如这般摄影路径,当然绝非他一人独有。远的暂且不说,就在中国当代摄影史上,摄影家与特定地域形成某种共生关系,以一格一格的底片记载视觉发现,再经过选择与编辑呈现出来的个案不胜枚举。张惠宾在这样的摄影史线索中有自己的位置,当属自然。

经作者苦心取舍放进《诗中原》中的作品,保留了未加裁切的形态,我们看到的正像大致可以视为负像的转印(反差之类的调整除外。这确乎也是张惠宾在大部分创作中坚持的习惯)。我强调这一点,并不是出于所谓构图研究的套路(这也是我前面使用“视框”一词而没有用“构图”的原因。前者是就结果而言,是名词;后者只是手法,是动词),而是因为我相当看重在纪实拍摄中对有效性信息进入画面的直觉化掌控。正是在这一点上,底片的存在我以为尤其重要。

张惠宾拍摄用的是135相机的50mm镜头,关于这一点我后面单说。这里首先要强调的是,众所周知,定焦镜头使用的难度在于其完全固定的取景范围,站位(机位)决定视框,它“一次性”地决定了画面的内容,你要传达的视觉信息被瞬间封存,理论上无法添加也无法删除。我甚至由此会饶有兴致地去想象摄影者拍摄时的进退步伐。

以我的摄影阅读经验,但凡用短焦距定焦镜头拍摄的纪实作品都十分耐看,我对这一点确信无疑!这样的作品,中心明确但并不被刻意强化,重心存在却不加以过分凸显,你不会忽略焦点所在,但进而又可以在画面上反复观看各个角落和每处细节,取景范围内的信息都可以被有效读取。这就是我所谓的“点在场中”。常被忽略的恰恰在于,这正是纪实摄影画面所带来的视觉收获与视觉感受,可以完全高于肉眼在现场直接观看的地方。就经验层面而言,“眼观”的每个瞬间都有个自然的聚焦点(实际上是一个相对窄小的关注点),受其支配,我们往往会对视野中的其他信息“视而不见”。在这个意义上,正是被定格的画面才让人得以真正对“这一刻”的瞬间进行不断的“重访”。更重要的是,优秀的纪实摄影并不仅仅只是用来填补由于多数人的缺席而产生的视觉空白,它可以进而使在场的拍摄者与不在场的观看者共同展开新的视觉发现。由此看来,反倒是长焦镜头在延续着我们肉眼的视觉习性,而不是所谓标准镜头符合我们的观看视野。

《诗中原》以黑白胶片进行拍摄,提到胶片不禁要多说几句。在关于纪实摄影的研究中,似乎不大有人去深入探究胶片拍摄和数码拍摄在摄影者工作方式、效果预判、时机选择,以及创作心理上的差别。往远些说,即便是在从业者众多的文学研究领域,也少有人去细致考察稿纸上手写和借助电脑写作在作家运思与行文,以及推敲反复上所可能有的变化。在我看来,这一关乎作品生成历史的研究相当有意义,理应成为美学批评的一个重要角度。具体到纪实摄影来说,底片之于摄影家犹如手稿之于作家,是极有价值的物质“痕迹”。和数码比较,不仅在于肯定有的数量差异(这实际上会大到惊人的地步)会导致拍摄上的不同考量,而且,前数码时代的作品相对来说可以从更原始的角度去判定现场的摄影行为。这是在研究纪实摄影作品时应该加以关注的地方。顺带一说,我在意物质“痕迹”,部分的原因是它很难被轻易篡改,而纪实摄影在本质上关乎“现实痕迹”,正是在这个意义上,胶片(底片)的退场使我们必须对可能的“反真实性”报以必要的警惕。当然,我并不是说胶片就意味着具有更大的真实性,所谓“真实性”一直是个复杂的问题,也并非可以轻易判定(摄影史上很多“假”的片子,在今天看来是另一种意义上的“真实”,但这只是历史地看,和这里所谈的现实选择没有关系)。这里仅仅是在最简单的层面上看待“真实”,并对胶片时代保有真挚的怀想。

就上述角度看,张惠宾的《诗中原》完成度相当高。可以看出,他对拍摄地域的生活十分熟悉,在现场有持续机敏的兴奋感,但仍然保持着适度的介入和审慎的拍摄态度。画面之所以耐看,不仅是因为出人意料的细节常常会引发读者的好奇心,更因为其敏感于“点”而不偏废“场”,使我们可以从中不断读出新的信息和意味。张惠宾习惯使用50mm定焦镜头(以下沿用习称“标头”)。在纪实摄影的谱系中有这种习惯的人并不少见(更有甚者会近乎“偏执”地只用这一种),为何如此,各家说法基本上大同小异。

我相信张惠宾之选择“标头”,如他所言,最初是生活困窘、“节衣缩食”所致。当年,很多人在摄影起步时都是在类似这般无奈之中别无选择地把标头视为了“初恋”。这又与现在不同。如今,大致是那种诸如28-85或24-105之类的所谓“标准变焦镜头”一下就成为了入门的首选。反倒是“标头”成了有争议的话柄:有人视其为“圣物”,把它说得云山雾罩、神乎其神;有人视其为“鸡肋”,偶尔装点门面,常常束之高阁。前者可能出自对摄影史上某些大师“神迹”的崇拜,而后者就认为其历史地位不过是特定条件下的产物,试问那些大师若是活在今天,敢保证他们就不会换装变焦?要说到“标头”的好处,大抵是光圈大、成像好、符合人眼视角云云。其他不论,就在中国纪实摄影家中,不乏运用“标头”的高手,而若要对此进行认真的考察分析,大概首先应该摆脱的正是这些似是而非的说法。

镜头看似只属于“器”(工具)的范畴,好像相较于题材表现和风格与观念而言,谈论它或显得有些“层级”不高。但以我之见,工具的使用实际上隐含着形上层面的问题。如墨性、笔性、纸性之于中国画,材料的性质不仅决定了形式与质地,更在本体意义上关联着创作主体对物象(客观世界)的认知与把握。

应该承认的是,摄影器材的进步自然延伸了我们的视觉能力,这无疑会极大地拓展人的创造性,并可能带来艺术表现力的提升。但是,本文只是针对“纪实摄影”,而问题恰恰就在这里。我的看法是,镜头实际上正在日益改变我们看待世界的方式,换句话说,是镜头而不是我们的眼睛在决定着我们对世界的呈现。它从对视觉的“模仿”出发,反过来又再造了我们的视觉。这无法避免,但就纪实摄影而言,我们仍然必须在最大程度上对其保留足够的谨慎。之所以要强调镜头之“器”的形上之“道”,因为在我看来,视觉观看与呈现,归根到底仍然是一种态度和立场的表达。

抛开解像力、色彩还原度等方面的改良不谈,有目共睹的“改变”主要在两个方面,其看似简单,但若稍加反思便会发现实质上非同小可。

首先是更大的光圈可以制造出更浅的景深,这导致那种称为“大光圈虚化”的视觉效果被越来越奉为一种艺术样式并逐渐使用泛滥。它以“主体突出”的名义将主体不适当地从环境中抽离,或许可以唯美并且煽情,但被抹去的背景使画面缺失了现实性依据和认识价值。我认为,它是一种关于塑造的美学(本质上是功利主义、商业意图和意识形态化的),而不应该让其轻易进入纪实摄影的领地。接下来更重要的一点是,超广角和更长焦距变焦镜头的运用。前者在对“主体侵略”的同时显出某种不自觉的轻慢与居高临下(顺带说一句,超广角拍摄带来的视觉效果,在我看来,实质上不是“靠近”,而是“推开”),后者则在可以轻易改变拍摄距离的同时,使摄影者处在某种“暧昧”的位置上,让其是否“真正在场”变得模糊不清。我认为,无论是“近身肉搏”式的“在场”,还是“长传冲吊”式的“在场”,都是可疑的“在场”。“在场”不是彻底的介入(推开),更不是遥距离的瞭望(拉近)。就此,真正的“在场”完全应该被看做是一种纪实摄影的哲学。

定焦镜头的大光圈化,其历史要远远早于变焦镜头。而仅仅是稍早些年的变焦镜头,其恒定(或广角端)的最大光圈不过就是f3.5,且变焦比有限。这实在要感谢器材制造商的努力与影人的追捧,假如不考虑重量与性价比,可以想象更大的进步随时可以到来。同样可以想象的是,纪实摄影正受到这种“进步”的侵蚀,并对其本质性构成消解。这并不是危言耸听。我曾经不乏调侃地将今天的摄影证候(“症候”)简单概括为“两高三大”——即高感光度、高速连拍,以及大光圈、大广角、大变焦。仔细想来,这些在今天的纪实摄影中也都或多或少的存在。一个简单的判断是,忽略事件和人物面貌等自身固有的年代感,你单单从画面的表现手法上就可以轻易分辨出过去和现在的作品的差异。如果再进一步比较摄影史上得到普遍认可的纪实作品,这种差异就会愈加清晰明显。

回到《诗中原》。我以为考察纪实摄影中“标头”的使用是可以“以张惠宾为例”的。从作品中我们不难看出他对这一镜头使用的娴熟,对其特性有充分的理解。他的画面体现出只属于“标头”的那种视觉特征,包括观察距离和空间感。而这种距离与空间感不仅是简单地出自一种物理尺度的丈量与艺术样式的判定,重要之处在于,它是由纪实摄影的内在品格所决定的。

和同道者一起看片,若作品使用“标头”拍摄,我便总会去强调这一点。我理解其使用上的困难,也理解靠近事件与人物去自然抓取需要一种恰当的态度与方法,所以阅读这样的作品在我更有乐趣。有意思的是,张惠宾的作品总会使我不断地要去判断他当时所处的位置与身体状态。或许一般去看作品时不用在意这些,更多只是直觉上的触动——对事、对人、对气氛等等。但若去深入阅读,便不应该轻易放弃这种判断所带给我们的意义。这是一种针对纪实摄影中真实的现场关系的考察,它恰恰建立在50mm镜头的使用基础之上。仅仅用《说书》(1994)来做个简单的分析。说书人沉醉在自己的状态中已然忘我,他完全忽略了相机的存在;观看的众人被说书人的神情与声音吸引,他们竟然也没有因为拍摄者的出现而转移注意力(快门的声响可能被淹没,也可能只是在“这一次”按动产生声音后才有人会投来一瞥);场面前方形成的“缺口”就是张惠宾所在的位置。这个位置稍偏一点,技术上说非常恰当,因为向右再挪一步就会使说书人与他背后的树干重合,同时也可以想象他的右侧还有观众。这里犹如传统戏剧观演中的“第四堵墙”,相当于面对“舞台”的位置。就现场来说,说书人是演员,旁人是观众;就摄影画面而言,所有人都是演员,我们才是观众。以拍摄状态来说,张惠宾在场,是观众中的一员;就完成的作品而言,张惠宾是“隐没”的人,我们的观看既通过他的在场也通过他的隐没才得以实现。这幅作品的创作手法具备了典型的使用“标头”的纪实摄影特征——恰当的在场,不扰动现场,也不隔绝于现场,并自然还原出现场的真实气氛。

张惠宾的片子大都体现出我所谓“恰当的在场”,是适度的融入,也是平视的观看。惟其如此,才自然而然,作品提供给我们的观看也才真实可靠。就像我们随在他的身后,或者说我们和他“共用”一个主观视角穿行于现场。对于中原,张惠宾不是游客,而是“返乡者”,更是社会学意义上的观察者。但他可以使我们成为游客,那种可以混迹其中的游客,进而,也可以使我们成为观察者。

我能想象,揣相机的张惠宾出没乡里的样子,他不是“侵入”的,而是“在场”的,更像是“熟人社会”中的一员。“标头”不仅最大限度地弱化了对场景和人物自在状态的侵扰,而且也使摄影者处在恰当、适度的位置上,不是置身事外的窥探,也不是不分彼此的纠缠。“标头”具有独特的力量。我在第一节中谈到摄影态度,在第二节中论及对有效信息的重视,以及这里强调的重要的“在场”,都可以部分归结于这种力量。

张惠宾的在场清晰可辨。对纪实摄影来说,清晰的在场就是有意义的在场。

摄影是一个复杂的整体,没有一种判断可以轻易宣称其有效作用于这个整体;即便仅仅是“纪实摄影”,对这个概念的使用也历来歧义多出。事实上,汉语中的理论批评话语时常困扰于概念表述的混乱,其成因与汉语的组词方式、西文转译、表述惯性、逻辑缺乏等等有关。俗话说“你懂的”,也只能按下不表。但概念的清理又时常显得非常必要,而不是多余的闲话。

简单说,我倾向于确立一种暂且可以称之为“社会摄影”的大类别,而把“纪实摄影”看做其中的一个子类别。前者是大概念,有统摄性的总体原则;后者是小概念,有其自身独具的一般原则。由此观之,无论从内容出发的社会立场分析,还是就形式而言的美学视角分析,对纪实摄影作品的解读都需谨慎——或者,会涉及社会效用的争执和目的性的纠缠,并稍不留心就被空泛的意义绑架;又或者,所谓艺术的批评话语往往失效,变成人云亦云的新八股。那么,若把《诗中原》视为这个概念区分中的纪实摄影的标本,又该如何看待其价值?

首先,我把《诗中原》视为一种本质意义上的纪实摄影文本。

在我看来,所谓本质意义上的纪实摄影,必然会表现出双重的背离——即对时间性(不是“时间”)与事件性(不是“事件”)的背离。它既不在时间性线索中强调历史演进与所谓进步正义,也不在事件性叙述中再现问题意识与价值评判。这种双重背离正是其区别于“社会摄影”中的其他子类别(比如新闻摄影、报道摄影)的根本所在。深一步讲,非本质的纪实摄影,无论时间性还是事件性的表达,其中都内置了意识形态话语和传播策略并强调特定的立场,它必须凭借完整的意义建构,才能成为社会整体叙事中的一环。

《诗中原》体现为一种朴素化与微观化的社会采样,没有预设的、刻意的观念意图(但并非没有观念),放弃先在的、被赋予的理性判断(也绝非缺乏理性)。它以摄影家之“我见”,提供的只是有关中原农村生活的生动的视觉切片。它不主动去建构宏大意义与激情说教,因而有着更加客观与直接的真实。它不刻意地制造视觉冲击和情绪刺激,因而人物和场面鲜活有趣,体现出亲切的平视的视角和知识分子发乎本能的乡土关切。从这个意义上也可以说,张惠宾属于那类立足于纪实摄影原点的摄影家,在纪实摄影中比较具有“原教旨”色彩。可以肯定的是,如他这类作品,具有更持久的观看价值,也更具备社会学意义上的认识价值。

其次,但同样重要的是,《诗中原》以强烈的现场感与丰富的视觉性,提供了真正属于纪实摄影的观看。

《诗中原》作为个体视角的乡村观察,拍摄于距今不算太远的胶片时代。可以肯定张惠宾扔掉的片子不在少数,追究片比、研究废片在我看来不仅没有意义,而且近乎学术八卦。事实上,对冲洗出来的底片进行仔细筛选,同样是摄影人必修的功课。如这般摄影路径,当然绝非他一人独有。远的暂且不说,就在中国当代摄影史上,摄影家与特定地域形成某种共生关系,以一格一格的底片记载视觉发现,再经过选择与编辑呈现出来的个案不胜枚举。张惠宾在这样的摄影史线索中有自己的位置,当属自然。

经作者苦心取舍放进《诗中原》中的作品,保留了未加裁切的形态,我们看到的正像大致可以视为负像的转印(反差之类的调整除外。这确乎也是张惠宾在大部分创作中坚持的习惯)。我强调这一点,并不是出于所谓构图研究的套路(这也是我前面使用“视框”一词而没有用“构图”的原因。前者是就结果而言,是名词;后者只是手法,是动词),而是因为我相当看重在纪实拍摄中对有效性信息进入画面的直觉化掌控。正是在这一点上,底片的存在我以为尤其重要。

张惠宾拍摄用的是135相机的50mm镜头,关于这一点我后面单说。这里首先要强调的是,众所周知,定焦镜头使用的难度在于其完全固定的取景范围,站位(机位)决定视框,它“一次性”地决定了画面的内容,你要传达的视觉信息被瞬间封存,理论上无法添加也无法删除。我甚至由此会饶有兴致地去想象摄影者拍摄时的进退步伐。

以我的摄影阅读经验,但凡用短焦距定焦镜头拍摄的纪实作品都十分耐看,我对这一点确信无疑!这样的作品,中心明确但并不被刻意强化,重心存在却不加以过分凸显,你不会忽略焦点所在,但进而又可以在画面上反复观看各个角落和每处细节,取景范围内的信息都可以被有效读取。这就是我所谓的“点在场中”。常被忽略的恰恰在于,这正是纪实摄影画面所带来的视觉收获与视觉感受,可以完全高于肉眼在现场直接观看的地方。就经验层面而言,“眼观”的每个瞬间都有个自然的聚焦点(实际上是一个相对窄小的关注点),受其支配,我们往往会对视野中的其他信息“视而不见”。在这个意义上,正是被定格的画面才让人得以真正对“这一刻”的瞬间进行不断的“重访”。更重要的是,优秀的纪实摄影并不仅仅只是用来填补由于多数人的缺席而产生的视觉空白,它可以进而使在场的拍摄者与不在场的观看者共同展开新的视觉发现。由此看来,反倒是长焦镜头在延续着我们肉眼的视觉习性,而不是所谓标准镜头符合我们的观看视野。

《诗中原》以黑白胶片进行拍摄,提到胶片不禁要多说几句。在关于纪实摄影的研究中,似乎不大有人去深入探究胶片拍摄和数码拍摄在摄影者工作方式、效果预判、时机选择,以及创作心理上的差别。往远些说,即便是在从业者众多的文学研究领域,也少有人去细致考察稿纸上手写和借助电脑写作在作家运思与行文,以及推敲反复上所可能有的变化。在我看来,这一关乎作品生成历史的研究相当有意义,理应成为美学批评的一个重要角度。具体到纪实摄影来说,底片之于摄影家犹如手稿之于作家,是极有价值的物质“痕迹”。和数码比较,不仅在于肯定有的数量差异(这实际上会大到惊人的地步)会导致拍摄上的不同考量,而且,前数码时代的作品相对来说可以从更原始的角度去判定现场的摄影行为。这是在研究纪实摄影作品时应该加以关注的地方。顺带一说,我在意物质“痕迹”,部分的原因是它很难被轻易篡改,而纪实摄影在本质上关乎“现实痕迹”,正是在这个意义上,胶片(底片)的退场使我们必须对可能的“反真实性”报以必要的警惕。当然,我并不是说胶片就意味着具有更大的真实性,所谓“真实性”一直是个复杂的问题,也并非可以轻易判定(摄影史上很多“假”的片子,在今天看来是另一种意义上的“真实”,但这只是历史地看,和这里所谈的现实选择没有关系)。这里仅仅是在最简单的层面上看待“真实”,并对胶片时代保有真挚的怀想。

就上述角度看,张惠宾的《诗中原》完成度相当高。可以看出,他对拍摄地域的生活十分熟悉,在现场有持续机敏的兴奋感,但仍然保持着适度的介入和审慎的拍摄态度。画面之所以耐看,不仅是因为出人意料的细节常常会引发读者的好奇心,更因为其敏感于“点”而不偏废“场”,使我们可以从中不断读出新的信息和意味。张惠宾习惯使用50mm定焦镜头(以下沿用习称“标头”)。在纪实摄影的谱系中有这种习惯的人并不少见(更有甚者会近乎“偏执”地只用这一种),为何如此,各家说法基本上大同小异。

我相信张惠宾之选择“标头”,如他所言,最初是生活困窘、“节衣缩食”所致。当年,很多人在摄影起步时都是在类似这般无奈之中别无选择地把标头视为了“初恋”。这又与现在不同。如今,大致是那种诸如28-85或24-105之类的所谓“标准变焦镜头”一下就成为了入门的首选。反倒是“标头”成了有争议的话柄:有人视其为“圣物”,把它说得云山雾罩、神乎其神;有人视其为“鸡肋”,偶尔装点门面,常常束之高阁。前者可能出自对摄影史上某些大师“神迹”的崇拜,而后者就认为其历史地位不过是特定条件下的产物,试问那些大师若是活在今天,敢保证他们就不会换装变焦?要说到“标头”的好处,大抵是光圈大、成像好、符合人眼视角云云。其他不论,就在中国纪实摄影家中,不乏运用“标头”的高手,而若要对此进行认真的考察分析,大概首先应该摆脱的正是这些似是而非的说法。

镜头看似只属于“器”(工具)的范畴,好像相较于题材表现和风格与观念而言,谈论它或显得有些“层级”不高。但以我之见,工具的使用实际上隐含着形上层面的问题。如墨性、笔性、纸性之于中国画,材料的性质不仅决定了形式与质地,更在本体意义上关联着创作主体对物象(客观世界)的认知与把握。

应该承认的是,摄影器材的进步自然延伸了我们的视觉能力,这无疑会极大地拓展人的创造性,并可能带来艺术表现力的提升。但是,本文只是针对“纪实摄影”,而问题恰恰就在这里。我的看法是,镜头实际上正在日益改变我们看待世界的方式,换句话说,是镜头而不是我们的眼睛在决定着我们对世界的呈现。它从对视觉的“模仿”出发,反过来又再造了我们的视觉。这无法避免,但就纪实摄影而言,我们仍然必须在最大程度上对其保留足够的谨慎。之所以要强调镜头之“器”的形上之“道”,因为在我看来,视觉观看与呈现,归根到底仍然是一种态度和立场的表达。

抛开解像力、色彩还原度等方面的改良不谈,有目共睹的“改变”主要在两个方面,其看似简单,但若稍加反思便会发现实质上非同小可。

首先是更大的光圈可以制造出更浅的景深,这导致那种称为“大光圈虚化”的视觉效果被越来越奉为一种艺术样式并逐渐使用泛滥。它以“主体突出”的名义将主体不适当地从环境中抽离,或许可以唯美并且煽情,但被抹去的背景使画面缺失了现实性依据和认识价值。我认为,它是一种关于塑造的美学(本质上是功利主义、商业意图和意识形态化的),而不应该让其轻易进入纪实摄影的领地。接下来更重要的一点是,超广角和更长焦距变焦镜头的运用。前者在对“主体侵略”的同时显出某种不自觉的轻慢与居高临下(顺带说一句,超广角拍摄带来的视觉效果,在我看来,实质上不是“靠近”,而是“推开”),后者则在可以轻易改变拍摄距离的同时,使摄影者处在某种“暧昧”的位置上,让其是否“真正在场”变得模糊不清。我认为,无论是“近身肉搏”式的“在场”,还是“长传冲吊”式的“在场”,都是可疑的“在场”。“在场”不是彻底的介入(推开),更不是遥距离的瞭望(拉近)。就此,真正的“在场”完全应该被看做是一种纪实摄影的哲学。

定焦镜头的大光圈化,其历史要远远早于变焦镜头。而仅仅是稍早些年的变焦镜头,其恒定(或广角端)的最大光圈不过就是f3.5,且变焦比有限。这实在要感谢器材制造商的努力与影人的追捧,假如不考虑重量与性价比,可以想象更大的进步随时可以到来。同样可以想象的是,纪实摄影正受到这种“进步”的侵蚀,并对其本质性构成消解。这并不是危言耸听。我曾经不乏调侃地将今天的摄影证候(“症候”)简单概括为“两高三大”——即高感光度、高速连拍,以及大光圈、大广角、大变焦。仔细想来,这些在今天的纪实摄影中也都或多或少的存在。一个简单的判断是,忽略事件和人物面貌等自身固有的年代感,你单单从画面的表现手法上就可以轻易分辨出过去和现在的作品的差异。如果再进一步比较摄影史上得到普遍认可的纪实作品,这种差异就会愈加清晰明显。

回到《诗中原》。我以为考察纪实摄影中“标头”的使用是可以“以张惠宾为例”的。从作品中我们不难看出他对这一镜头使用的娴熟,对其特性有充分的理解。他的画面体现出只属于“标头”的那种视觉特征,包括观察距离和空间感。而这种距离与空间感不仅是简单地出自一种物理尺度的丈量与艺术样式的判定,重要之处在于,它是由纪实摄影的内在品格所决定的。

和同道者一起看片,若作品使用“标头”拍摄,我便总会去强调这一点。我理解其使用上的困难,也理解靠近事件与人物去自然抓取需要一种恰当的态度与方法,所以阅读这样的作品在我更有乐趣。有意思的是,张惠宾的作品总会使我不断地要去判断他当时所处的位置与身体状态。或许一般去看作品时不用在意这些,更多只是直觉上的触动——对事、对人、对气氛等等。但若去深入阅读,便不应该轻易放弃这种判断所带给我们的意义。这是一种针对纪实摄影中真实的现场关系的考察,它恰恰建立在50mm镜头的使用基础之上。仅仅用《说书》(1994)来做个简单的分析。说书人沉醉在自己的状态中已然忘我,他完全忽略了相机的存在;观看的众人被说书人的神情与声音吸引,他们竟然也没有因为拍摄者的出现而转移注意力(快门的声响可能被淹没,也可能只是在“这一次”按动产生声音后才有人会投来一瞥);场面前方形成的“缺口”就是张惠宾所在的位置。这个位置稍偏一点,技术上说非常恰当,因为向右再挪一步就会使说书人与他背后的树干重合,同时也可以想象他的右侧还有观众。这里犹如传统戏剧观演中的“第四堵墙”,相当于面对“舞台”的位置。就现场来说,说书人是演员,旁人是观众;就摄影画面而言,所有人都是演员,我们才是观众。以拍摄状态来说,张惠宾在场,是观众中的一员;就完成的作品而言,张惠宾是“隐没”的人,我们的观看既通过他的在场也通过他的隐没才得以实现。这幅作品的创作手法具备了典型的使用“标头”的纪实摄影特征——恰当的在场,不扰动现场,也不隔绝于现场,并自然还原出现场的真实气氛。

张惠宾的片子大都体现出我所谓“恰当的在场”,是适度的融入,也是平视的观看。惟其如此,才自然而然,作品提供给我们的观看也才真实可靠。就像我们随在他的身后,或者说我们和他“共用”一个主观视角穿行于现场。对于中原,张惠宾不是游客,而是“返乡者”,更是社会学意义上的观察者。但他可以使我们成为游客,那种可以混迹其中的游客,进而,也可以使我们成为观察者。

我能想象,揣相机的张惠宾出没乡里的样子,他不是“侵入”的,而是“在场”的,更像是“熟人社会”中的一员。“标头”不仅最大限度地弱化了对场景和人物自在状态的侵扰,而且也使摄影者处在恰当、适度的位置上,不是置身事外的窥探,也不是不分彼此的纠缠。“标头”具有独特的力量。我在第一节中谈到摄影态度,在第二节中论及对有效信息的重视,以及这里强调的重要的“在场”,都可以部分归结于这种力量。

张惠宾的在场清晰可辨。对纪实摄影来说,清晰的在场就是有意义的在场。

Photographer Zhang Huibin and His “Poetizing The Central Plain”

Jin Ning

When reading Poetizing The Central Plain, it has been a wonderful journey. This was not only because that I’m interested in picture itself, but also the scene and characters it provide, more importantly, I saw some even more precious qualities within the images: Solid but not rhetoric, direct but not vulgar, balance but not weird, humor but not sarcastic.

Photography is a complex whole, not a judge can easily claim that its effective role in the whole; Even just "documentary photography", the use of this concept also has traditionally been more ambiguity. In fact, the Chinese concept theory on often in critical discourse expression of chaos, the causes and the Chinese way of groups of words, expression of western translation, inertia, lack of logic and so on. As the saying goes, "you know", also can press the table. But the concept of clear and often seem to be very necessary, rather than excess of gossip.

Simply, I tend to establish a large category can be called "social photography", and "documentary photography" as one of the child categories. The former is big concepts, with an overall principle; the latter is a smaller concept, has its own unique general principles. Therefore, regardless of the interpretation of documentary photographic works from a social position analysis, or from the perspective of aesthetic form, both need to be careful—Or, when the so-called art criticism words fail. If, considers “Poetizing The Central Plain” as specimens to distinguish the concept of documentary photography, then how to evaluate its value?

First of all, I take in the work “Poetizing The Central Plain” as an essential documentary photography text. For me, which mean, will result in a double deviation - that is, the timeliness (not "time") and eventness (not "events"). This dual deviation distinguishes it from other "social photography" such as news photography, reportage photography, etc. In another word, documentary photography, whether it's timeliness or eventness, has built-in ideological discourse and specific speaking position, which lies in a complete reconstruction, to become a part of the society narrative.

Poetizing The Central Plain embodies in a simple chemical and micro social sampling, no default, no deliberate intent, to give up existed and given rational judgment. Provided it with the photographer. As "my opinion" of the photographer, only provides a vivid visual slice of the Central Plain rural life in China. It not actively construct a grand and passionate preaching, and thus have a more objective and direct reality. Because it is not deliberately creating visual impacts and emotional stimuli; thus to have fresh characters and scenes, and reflects a kindness concerns of intellectuals.

Secondary, and further, “Poetizing The Central Plain” uses a strong sense of presence and rich visualization to provide a real way of seeing for documentary photography.

The Poetizing the Central Plain is taken from an observer's perspective during the film camera era. Certainly, Zhang Huibin must waste a lot more negatives before getting to here. In fact, to carefully screen out excellent negatives is a required course for all photographers.

Those photos in the album of "Poetizing The Central Plain" that he screens out from the numbers of negatives, are retained without cutting shape. I emphasize this point, not to follow the so-called composition method (which is in front of me, using the word "frame" and not "composition". The former is in terms of the results, and is a noun; the latter is a technique, is a verb), but because I am quite the value of intuitively controlling the core valid information in the image of the documentary photograph. It is at this point, the existence of negatives I think is particularly important.

Zhang Huibin utilizes the camera 135 with 50mm lens, I'll discuss further about it in the article." Here, first of all, as we known, the difficulty of using a prime lens lies in its completely fixed frame, position decides the frame, it determines the content of the image "one-off", the visual information that you want to convey is instantly sealed, theoretically no adding or deleting.

Based on my experience of shooting, any photos shot by a short-focus fixed lens makes the picture more attractive. I have no doubt about that!

Such works, the main idea are clear, but not stressed, not overly highlighted, you would not ignore what the camera focusing, but be able to look at other details and every corner. This is what I call "points are all in the field". This is one thing that we often neglect, but I believe that this is exactly the visual genius that documentary photography offers, which is completely more than what we can get at the scene by directly watching through our naked eye.

Based on experience level, there is a natural focus point in every single moment of "eye view", (which is actually a relatively small focus point), at its disposal, we tend to "blind" out all other information in the picture. In this sense, what we captured at a certain moment indeed creates possibilities for people “revisit" again and again. And more importantly, in face, excellent documentary photographers are not only filling in visual blanks for those people who are absent from the story, but also make both people in the image and the outside viewer discover new things. Instead, it is that telephoto lens continues our visual habit, rather than standard lens fit our viewing angle.

“Poetizing The Central Plains” shoots in black and white film, when speaking of film, I could not help to say a few more words. In the study of documentary photography, it seems unlikely that someone dives deep into both film and digital shooting techniques such as the way of shooting, prejudgment of effect, timing, and the difference psychologically of creation. Additionally, even in the field of literature study, few people dive deep into the study of how writing materials (handwriting or electronic writing) would affect writers’ writing ideas. In my opinion, this is a quiet field of study, and also could be an important point of view in aesthetic criticism.

Specifically, in documentary photography, the significance of negatives to a photographer is like a manuscript to an author, is a valuable "trace". Compared to digital, somehow lead to different considerations on shooting, and, determine the shooting behavior from its initial perspective. This is an area need to be focused when studying documentary photography works. Based on the point of view, Zhang Huibin’s photographic work“Poetizing The Central Plains” is done very well. As you can see, he is very familiar with the shooting area's life, and has a continuous excitement at the site, but still maintains a moderate attitude towards shooting. The photographs are quite attractive, not only because of unexpected details, but also because of its sensitive to “focus points” while concerning about the whole scene; which make us constantly discover new information and meaning.

Zhang Huibin always uses a 50 mm prime lens (called “standard lens” in the following paragraphs) for his photographs. It is a not common “behavior” in the documentary photography world; and critics have different opinions about this habit. In my opinion, his choice of “standard lens” is simply a result of his poor personal financial condition at the beginning period of his photographic career. In those days, many people started their photography career with a “standard lens”, and called it the “first love”. It is quite different from now. Now, a common choice for beginner photographers is generally a 28-85mm or 24-105mm lens. People have their own opinion on the trendy phenomenon, some believe that it probably because of the worship-like kind of imitation; the others believe that it is only an inevitable process during the popularization of photography is China. No matter what, there are indeed some excellent, ““standard lens” documentary photographer in China.

Admittedly, the camera lens is gradually changing our way of seeing the world. It greatly expands people's creativity; but from visual "imitation", it inevitably changes our vision in turn. In terms of documentary photography, we have to maximally keep our cautiousness towards it. Because in my opinion, the visual view and presence, is ultimately an expression of one's attitude and position. Not include power and changes in color reduction degrees, there are mainly two different “changes” in two aspects, they might looks be like simple, but if a little reflection will be found in essence.

Back to the work series “Poetizing The Central Plains”, I thought the best example of using “standard lens” can be Zhang Huibin. From his work, it is not hard to notice that his excellent mastery over the specific type of camera lens, and posses a comprehensive understanding of it. His image reflects visual features only could be produced by a “standard lens”, including the observing distance and the feeling of space. However, this kind of distance and space is not simply a result of physical measurement, but also a result of art style judgement. The quality of such result depends on the inherent character of documentary photography.

What’s Interesting, Zhang Huibin works always make me constantly look for his position when taking the photo. Generally, we don’t look at a work caring about this question. But think further, we should not give up in the meaning of this judgement brings to us. This is a study of inside relationship of a documentary photography work; coincidentally, it is based on familiarity of using a 50 mm lens.

Take the picture “Monologue Storyteller" (1994) as an example, the storyteller get himself immersed in his own ecstasy, and totally ignores the existence of the camera; the audience downstage is completely attracted by the storyteller's facial expression and voice, they are not distracted by the involvement of the photographer (shutter sounds may be submerged, just only this "one time" click sound making people look at the camera). This position is slightly remote, but the technique is appropriate, as when slight move to the right, it could make the storytellers overlap with the tree behind him. Here it seems to be the "fourth wall” in a traditional drama show stage. In the scene, storytellers is an actress, others are the audience; In terms of the photographic image, everyone is an actor, we are the audience. In a camera mode, Zhang Huibin is in presence, is a member of the audience too; for the finished photo work, Zhang Huibin is “missing", but he is not missing in fact. The paradox itself seems interesting to me. This photograph has the every typical feature that a “standard lens” could produce— appropriate presence, no disturbance, not insulated, but has a natural restoration of the actual scene.

Most of Zhang Huibin’s photographs reflect what I call “appropriate presence", is a kind of modest integration with a scene. Only in this way, naturally, his work gives us a reliable way of seeing. Just like we're following him, and we "share" one subjective perspective walking across on the site. In the central plains, Zhang Huibin is not a tourist, but someone who “returns" home, and becomes a sociological observer. But he can make us become a tourist, that can blend of tourists, in turn, also can make us become the observer.

I can imagine, when Zhang Huibin appears in villages carrying his camera, he is not “invading”, not a outsider at all.

“Standard lens" has a unique power. My attitude towards photography was mentioned in the first section, and in the second section I discussed an emphasis on effective information, here I am emphasizing the important of “presence”, which is a strong power that attributes to most scenarios in photography.

Zhang Huibin’s presence is clearly identifiable. For documentary photography, presence is critical.

(Jin Ning, Photography critic Deputy Editor of “Art Research”)

豫公网安备 41019602002106号

豫公网安备 41019602002106号