赵震海

1949年生于河南长垣县。

1968年——1976年在解放军某部从事文艺工作。

1973年——1978年在某县委宣传部从事摄影工作。

1980年——1995年在某市文化馆从事摄影创作。

1986年加入中国摄影家协会。

1987年毕业于沈阳鲁迅美术学院艺术摄影系。

1995年——2000年在《大河报》人摄影记者及图片编辑。

获奖:

1989年《各有情趣》获文化部全国摄影铜杯奖。

1985年《珠撒山林》获中国首届黑白摄影艺术展览铜杯奖。

1984年《钢筋铁骨》、《够有情趣》同获《中国摄影》杂志年赛三等奖。

1983年《好孙女》获《中国摄影》杂志年赛二等奖,并载入《中国摄影年鉴》。

展览:

2004年9月平遥国际大展展出《父母》系列黑白摄影作品34幅。

2004年6月16日在升达大学举办赵震海、汉斯·汤姆摄影联展,作品共60张

2003年8月广州美术馆摄影收藏展入选作品《如厕问题》、《过河收割》、《养蚕人》等3幅。

1996年5月北京“北斗星”画廊举办赵震海个展《矸石山上的捡煤人》作品25幅。

1993年《矸石山上的捡煤人》作品8幅,其中6幅作品同时在法国摄影节上展出。

1985年《金色年华》入选第三届国际影展并刊登在1985年3期《中国摄影》杂志上。

出版:

2005年北京紫图图书出版公司出版《中原密洞》图片及相关文字共10个页码。

2005年《人民摄影报》刊出《中原父老》8张,文约600字。

2003年《摄影之友》3期创作版刊出独幅照片《盲人行》。

2002年5月《视觉21》杂志刊发自行车摄影作品4幅。

2001年10月5日《中国摄影报》作品版刊出《都市》摄影作品5幅。

2001年6月《视觉21》杂志刊发组照《狂城乱马》18幅,文千字。

2001年5月15日《人民摄影报》1版刊发封面独幅大照片《黄河从门前流过》

2001年4月《视觉21杂志》刊发摄影作品11张,文700字(视觉中国栏)。

2001年4月20日《人民摄影报》作品版刊发《行走》作品6幅文300字

2001年4月11日《人民摄影报》作品博览版刊发摄影作品4幅。

2001年2月7日《人民摄影报》作品博览版刊发《都市人》作品6幅,文字300字。

2001年元月23日《中国摄影报》刊发论文《人体写真写什么》约3000字。

2001年元月19日《中国摄影报》8版整版刊发《道口》作品9幅及相关文字。

1996年《大众摄影》杂志8期刊发《影中人》摄影作品二幅

1996年《中国摄影》杂志第四期刊发赵震海《中原一代传统农民》作品集评价文字。

1996年8月浙江摄影出版社出版赵震海《中原一代传统农民》摄影专辑。

1994年《中国摄影》杂志刊出《山里的会》展览作品8幅,文2500字。

1994年《中国摄影》从第2期开始刊出文论《真诚·朴素·自由》连载9期约2500字。

1994年3月11日《人民摄影报》封面刊出独幅作品《盲人行》。

1993年台湾第10期《摄影家》杂志“中国摄影专辑”刊发《矸石山上的捡煤人》作品8幅,文2500字,其中6幅作品同时在法国摄影节上展出。

1989年《中国摄影家》杂志第五期刊发摄影作品3幅。

1985年《中国摄影》杂志第四期“我的艺术追求”栏目刊发《戏迷》等4幅作品及短文。

Zhao Zhenhai

1949 born in Changhuan, Henan.

Served at The people's liberation army

Served as photographer at a County Committee propaganda department.

Served in photographic creation at city municipal cultural center

Joined China’s Photographer’s Association

Graduated from Shenyang Luxun academy of fine arts, department of photography.

Served as photographer and photo editor at the River Newspaper

Awards

The third prize of The ministry of culture national photography

The third prize of China's first black and white photography art exhibition

The third prize of China Photography magazine competition

The second prize of China Photography magazine competition

Exhibitions

2004 “parents” black and white series, Pingyao international Photography Festival

2004 Photography Exhibition of Zhao Zhenhai And Hans Tom, Shengda University

2003 “toilet problem”, “crossing the river by harvest”, “sericulture people” , Guangzhou museum of art

1996 “pick up coal gangue mountain people”, Zhao Zhenhai Solo Exhibition, Beijing “dipper” galleries

1993 “The man picking up coal on gangue mountain”, photography festival, France

1985 “Golden years”, the third China international film festival

Publications

2005 “The Central Plain Secrete Cave”, Beijing purple picture book publishing company

2005 “the central plain folk people”, People's photography newspaper

2003 “ Walking with the blind”, Friends of Photography Magazine

2002 “Bicycles”, Vision 21 Magazine

2001 “Urban cities”, China Photography Newspaper

2001 “Crazy City”, Vision 21 Magazine

2001 “The Yellow River running cross the door ”People’s Photography Newspaper

2001 “walking” People’s Photography Newspaper

2001 “Urban People”, People’s Photography Newspaper

2001 Article “What is nude portraits?”, China Photography Newspaper

2001 “the street cross”, China Photography Newspaper

1996 “A generation of traditional Central China farmers ”, China Photography Journal

1996 “A generation of traditional Central China farmers ”, Zhejiang photography publishing

1994 “Meeting in a village”, China Photography Journal

1994 “sincere, simple, and Freedom “, China Photography Journal

1985 “Opera Fans” ,China Photography Journal

还农民以生存本相

痛苦中的执着

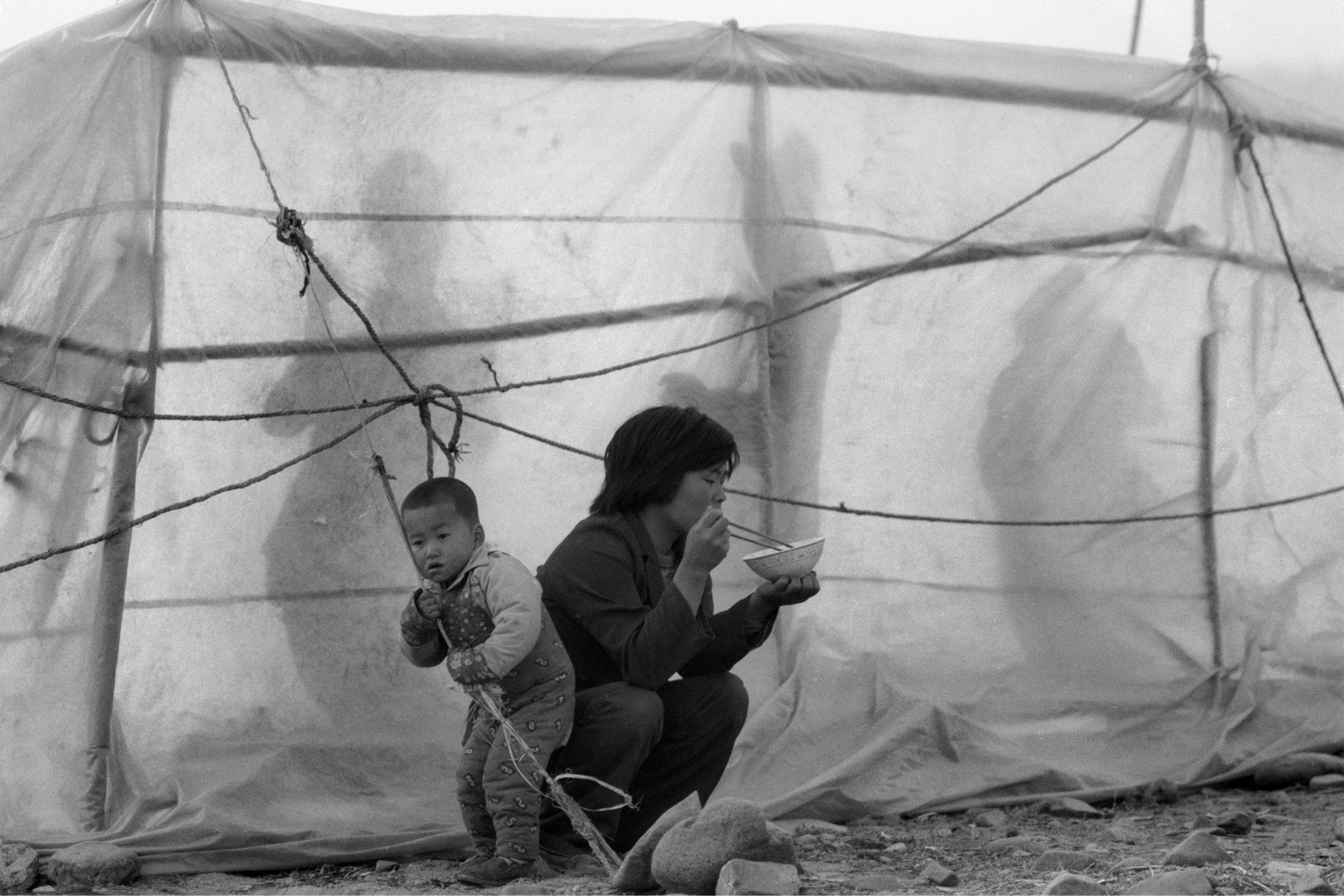

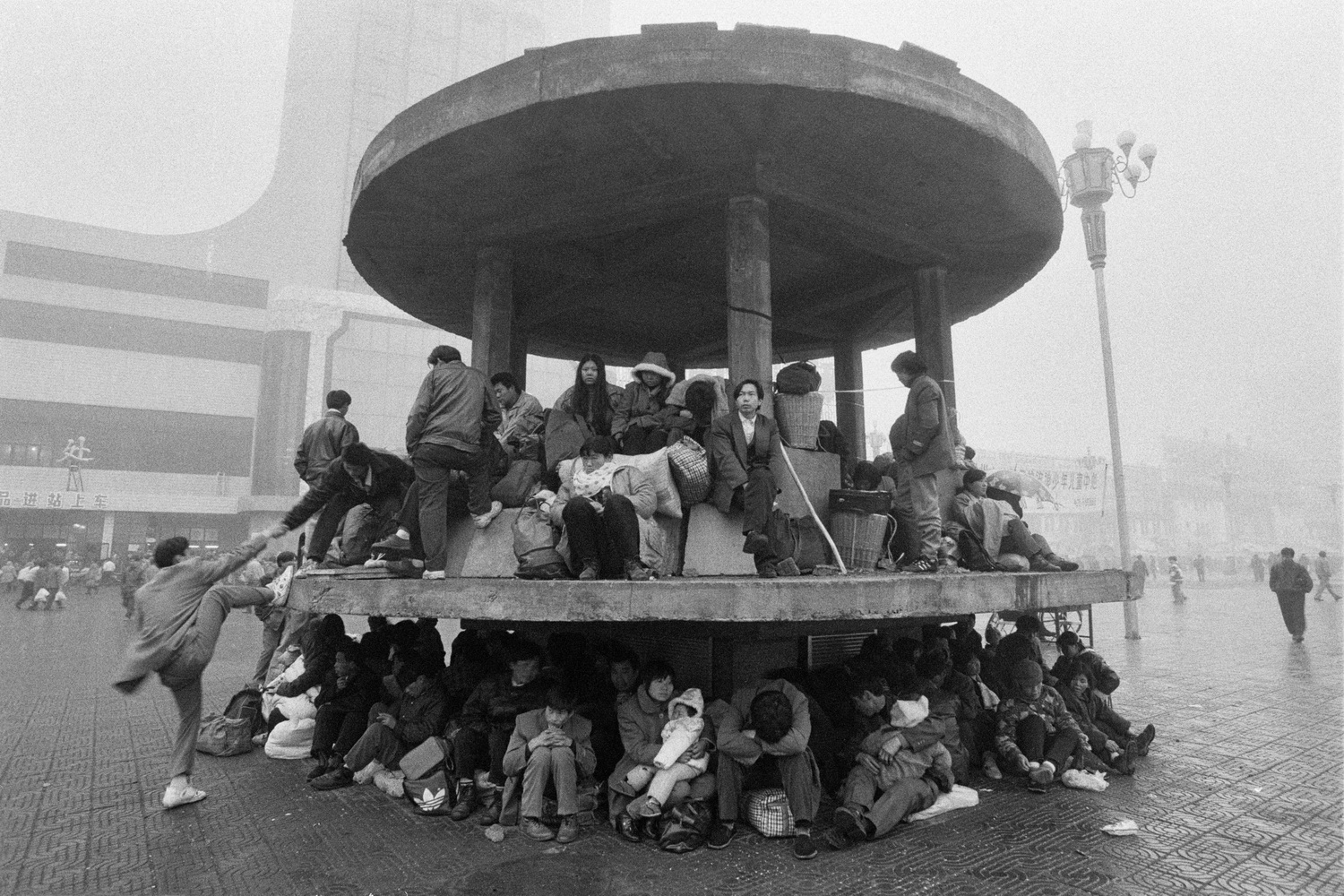

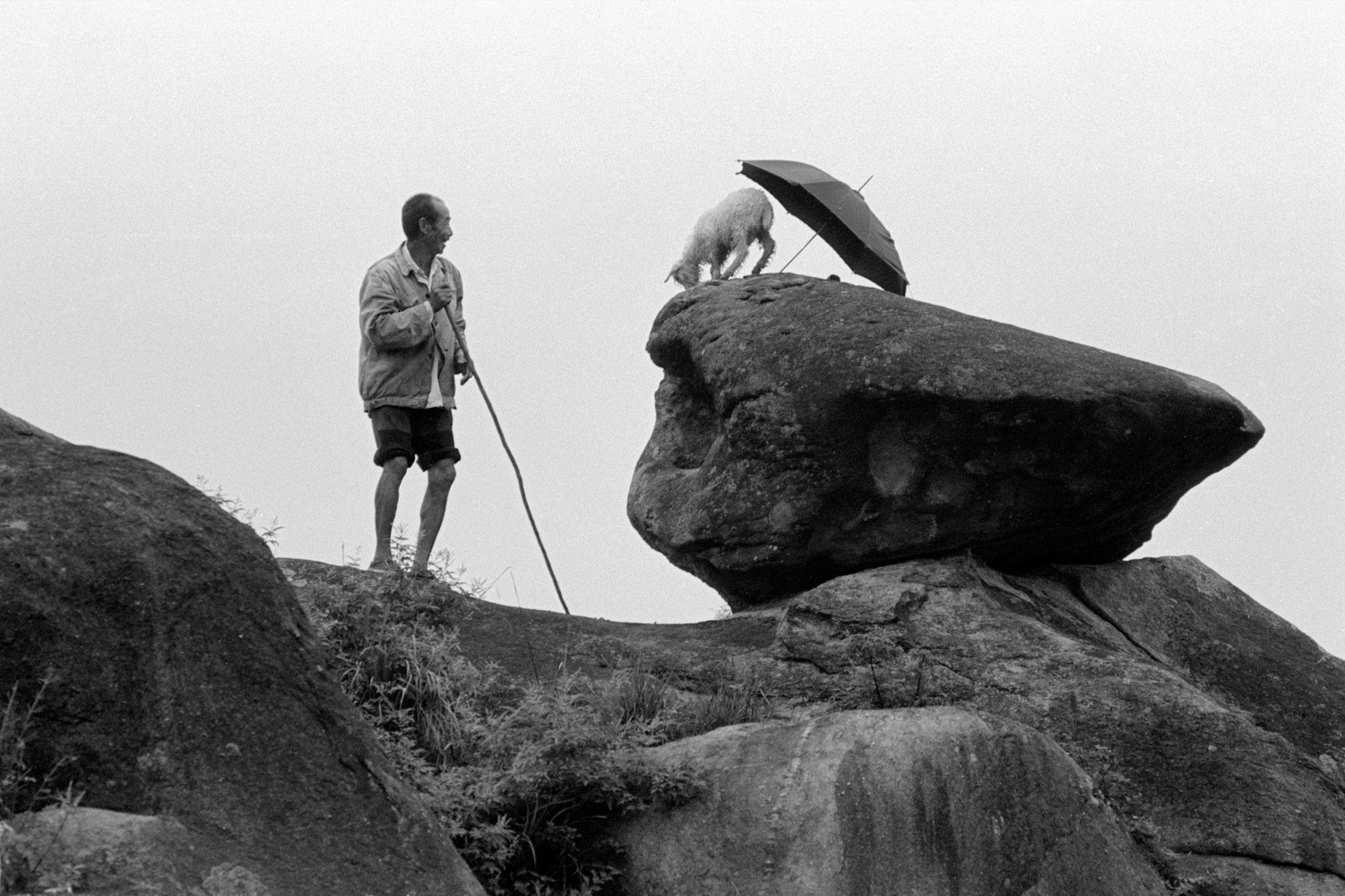

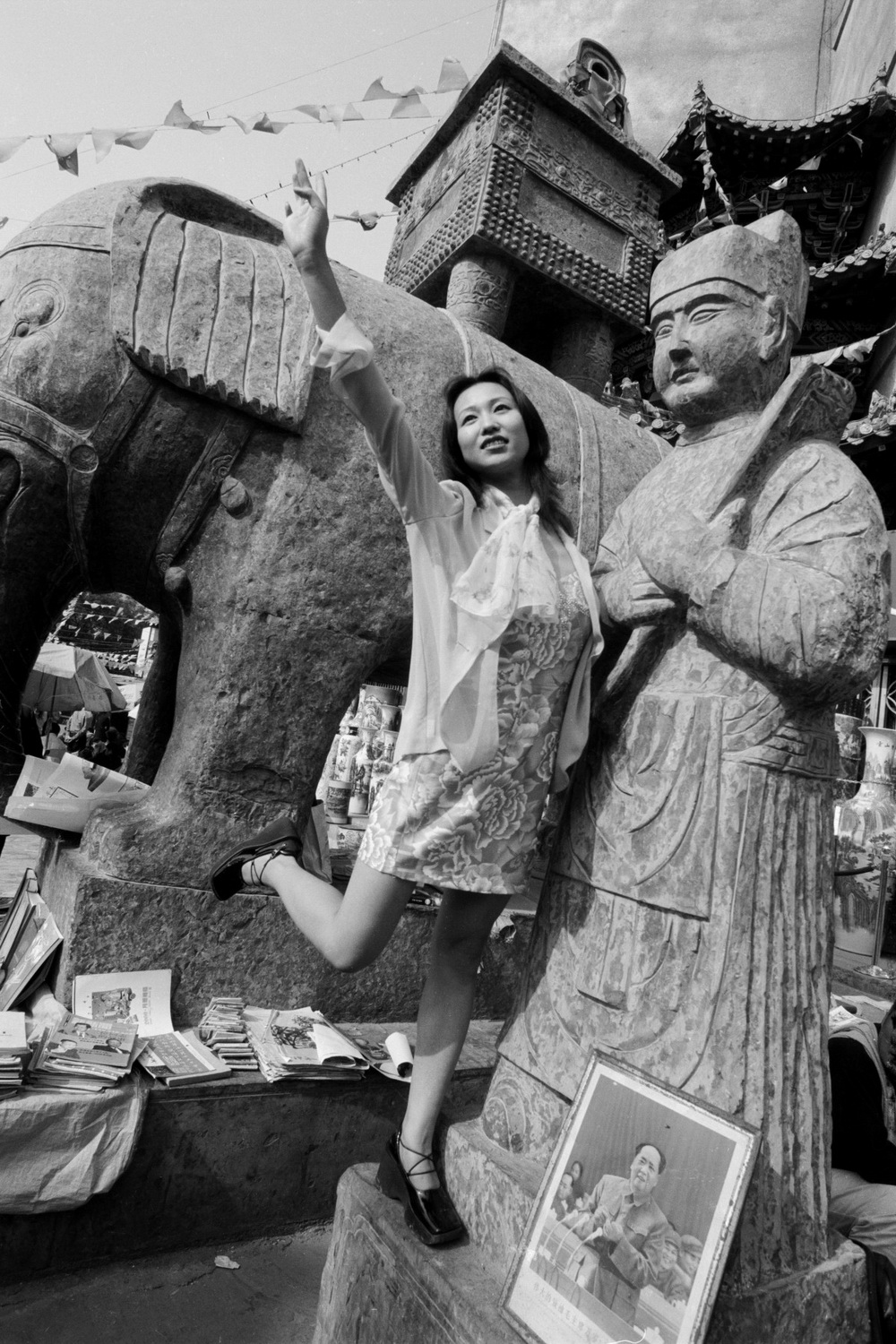

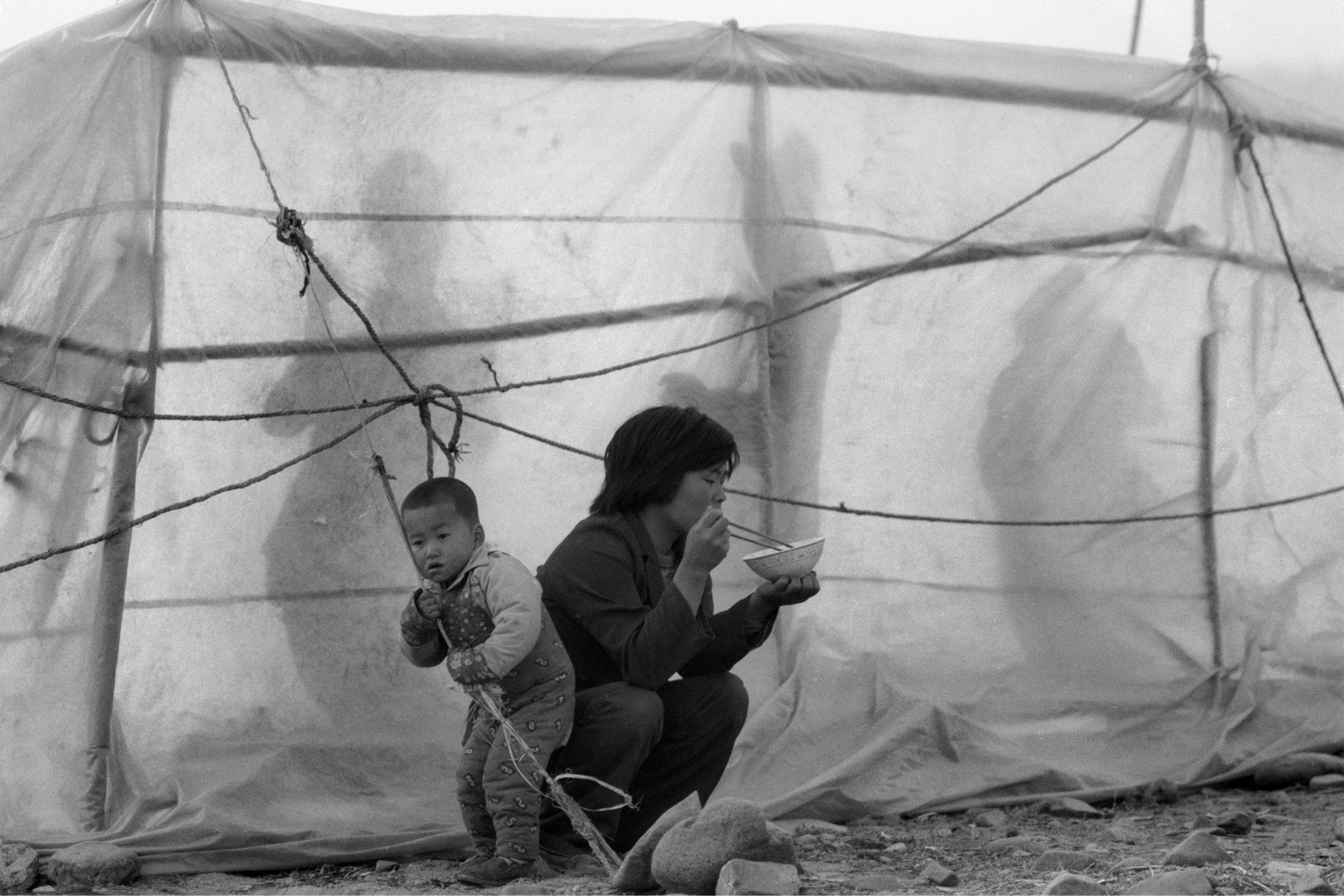

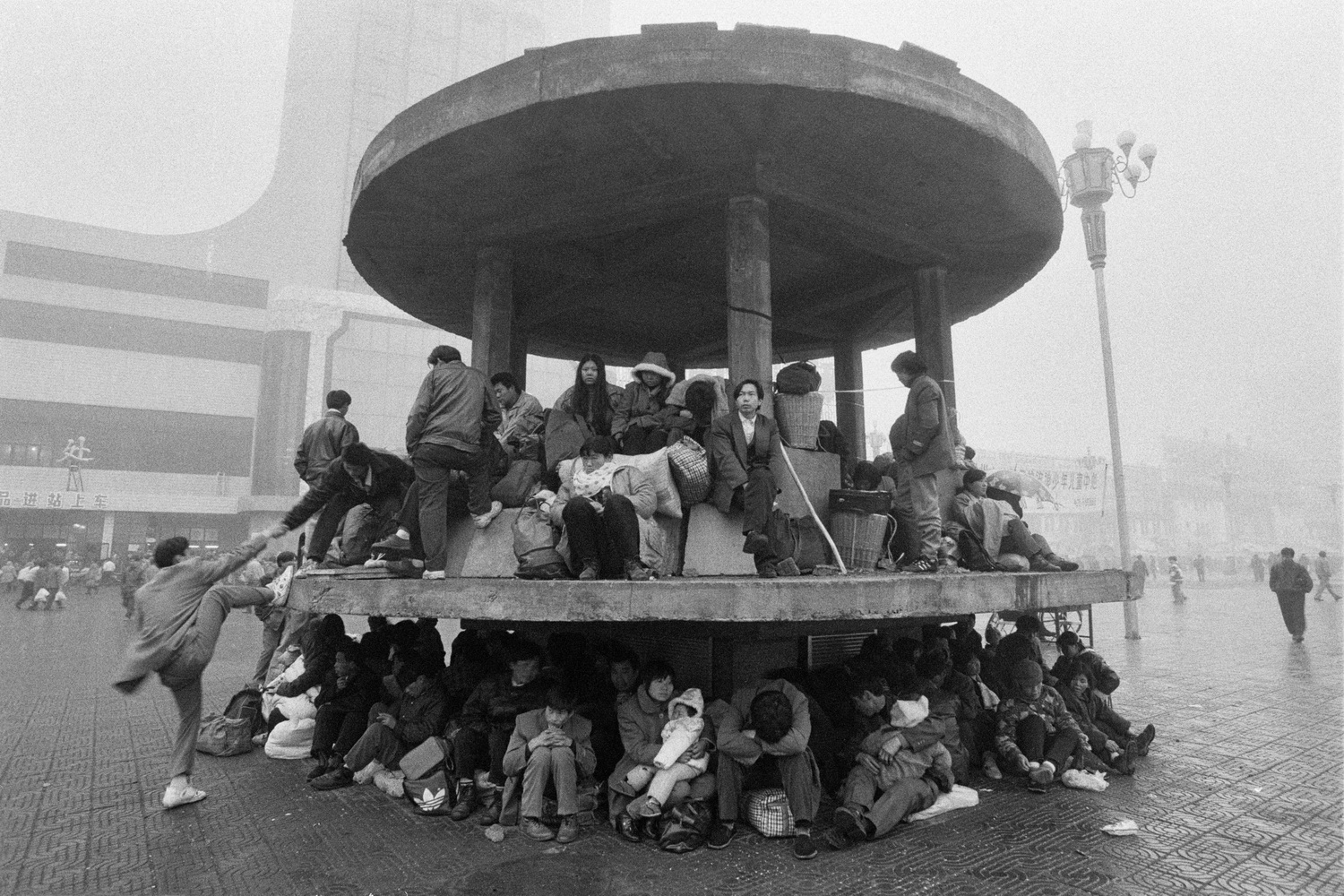

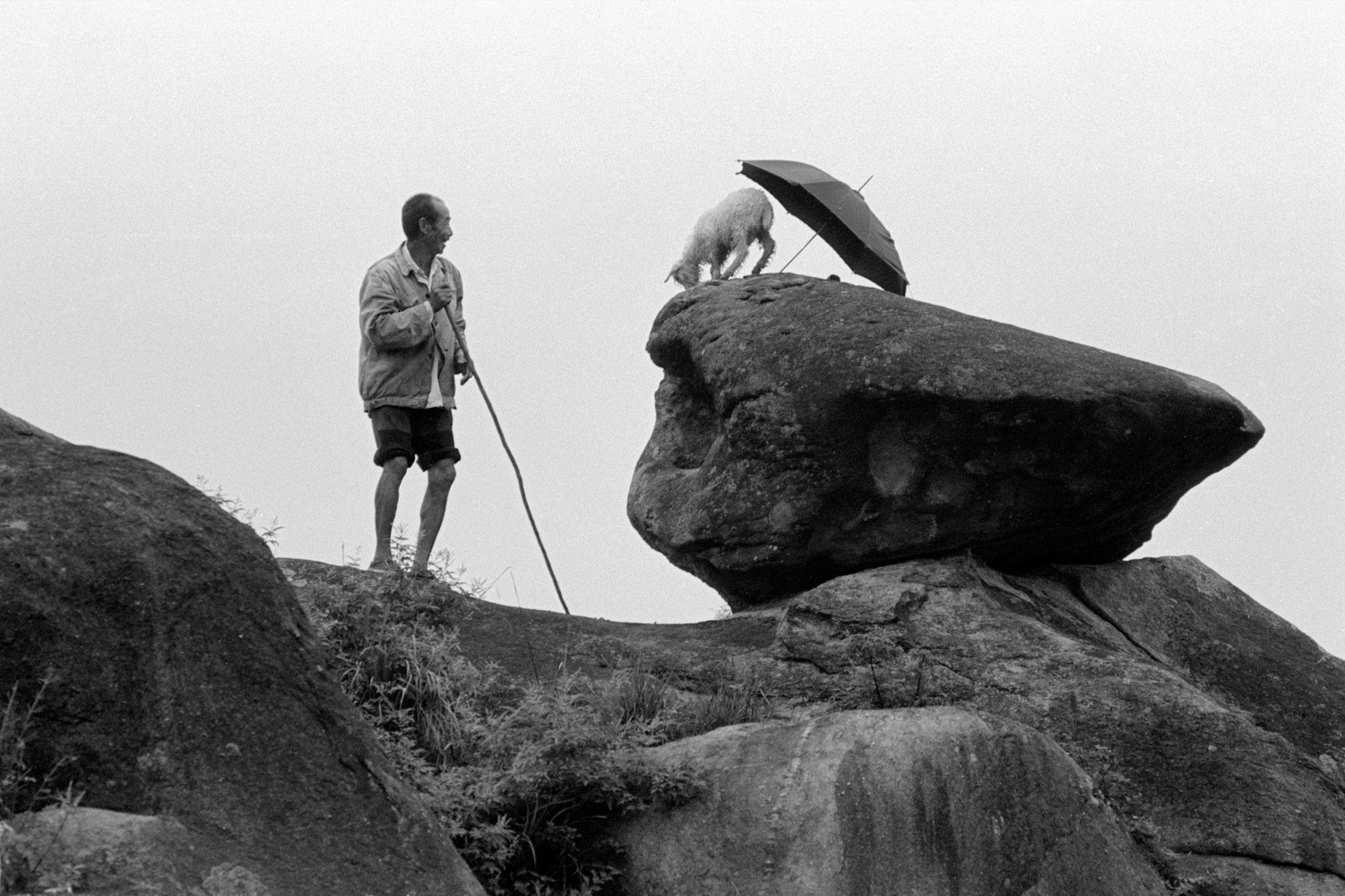

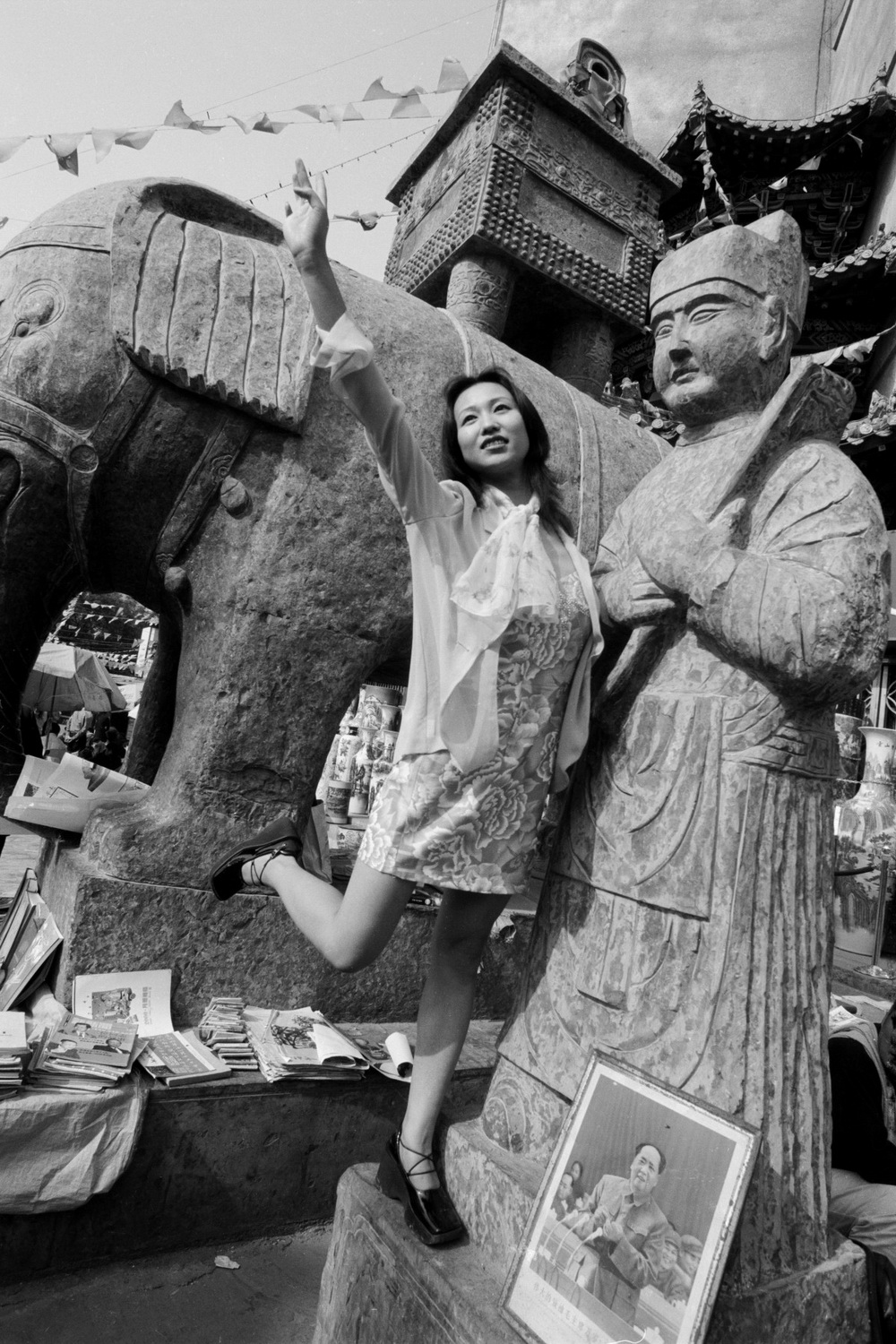

赵震海主要把镜头对准了农村农民,他的思想来源其一是血缘情感,他说我的父母和父母的父母都是农民,我没有理由不将镜头对准他们;其二是历史意识:“降生在旧中国的那一代传统农民正在一个个相继离去,尽快用相机留住他们,留住他们便是留住了一段历史。”(赵震海《还农民以生存本相》)1996年他的第一部作品集《中原·一代传统农民》问世,这部农村影像成为珍贵的历史文献。赵震海非常明白他面对的是中国最大的当时还非常贫穷的弱势群体,也非常明白照相机天生的侵略性自己的拍摄是一种对他们的掠夺,赵震海极力地小心翼翼地避免对他们的伤害。生活非常艰苦劳累的矸石山捡煤人都是附近县乡的农民,他把他们看做自己的父兄姐弟,对他们抱着一腔亲情,他认为亲情超越了同情,同情不够,还带有居高临下的成分,应该是一种纯粹的认同或等同。这种认识是上世纪90年代初中国纪实摄影人道主义的精神成果。摄影家以平等、认同的姿态对待相对弱势的拍摄对象表现出一种人文情怀,并且获得心理的平衡:“由于有了位置上的平等关系,我虽从他们那里取走了自己所要的东西——照片,但也决不再是非道德的掠夺。”(赵震海《我拍矸石山上采煤人》)但是赵震海并没有因此心安理得,一种精神上的无奈和痛苦一直伴随着他的纪实摄影,因为虽然“道德地”从他们身上取走了照片,但是照片对改变他们生活的困难毫无帮助:“作为一个普通拍摄者,我常常思考,自己的影像能给社会带来些什么?那些偏远山乡的缺衣少食者,还有那里的失学儿童们,你的影像能让他们重返学堂吗?还有那些缺医少药者,你能医治他们的病痛吗?想到这些便生出‘选择摄影也许是个错误’这样的念头,因为我们眼见着不少人缺衣少食,儿童为此辍学,可是,无助的摄影对此却一筹莫展。于是,我不再像昔日那样对摄影梦萦魂牵,因为他太懦弱,太无用!”(赵震海《为农民造像》)摄影使他看到了更多的贫穷苦难,却无助于他悲天悯人的情怀,激愤的言辞透出内心的痛苦。有多少摄影家像赵震海一样承受着这样的痛苦?

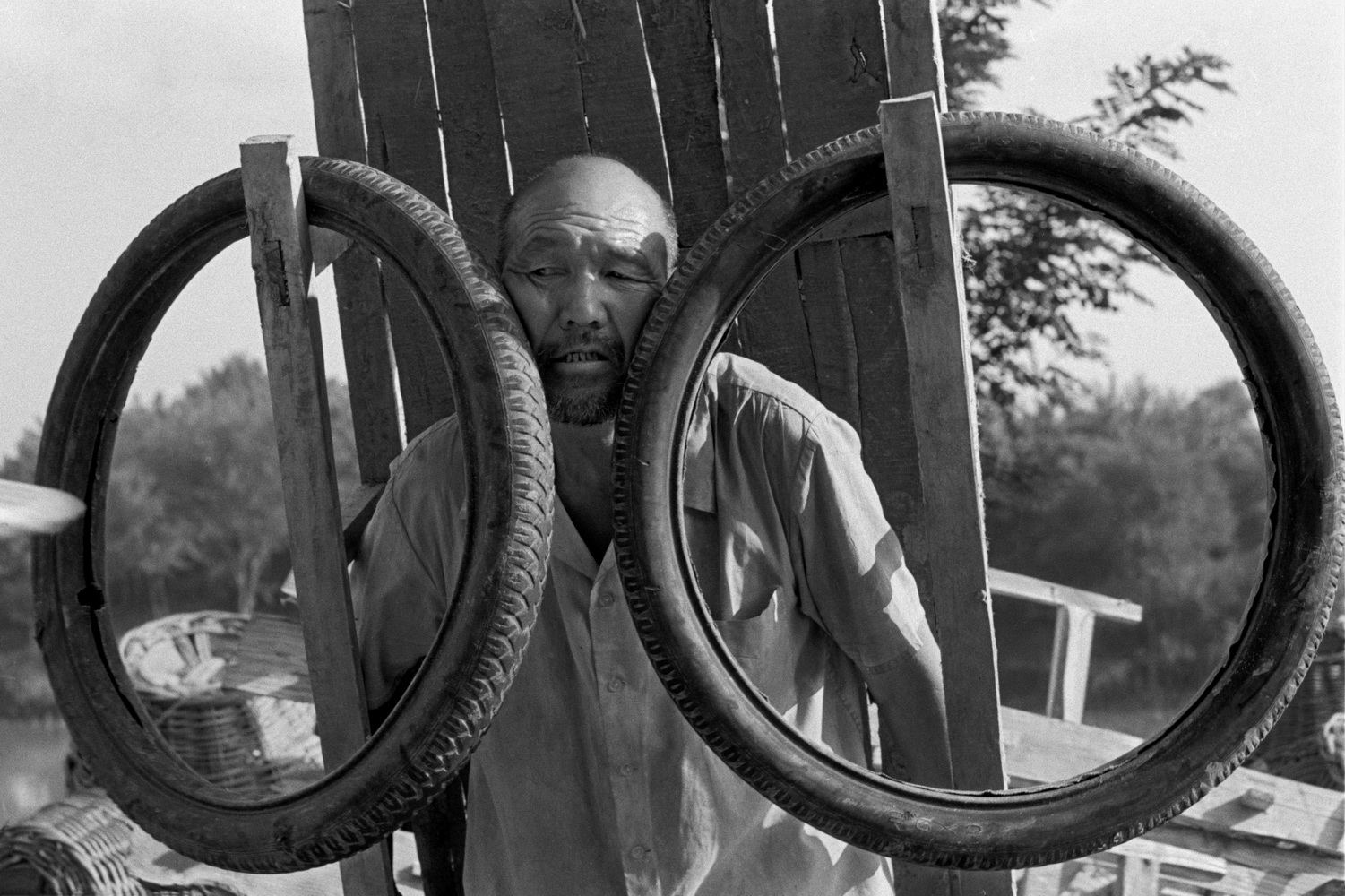

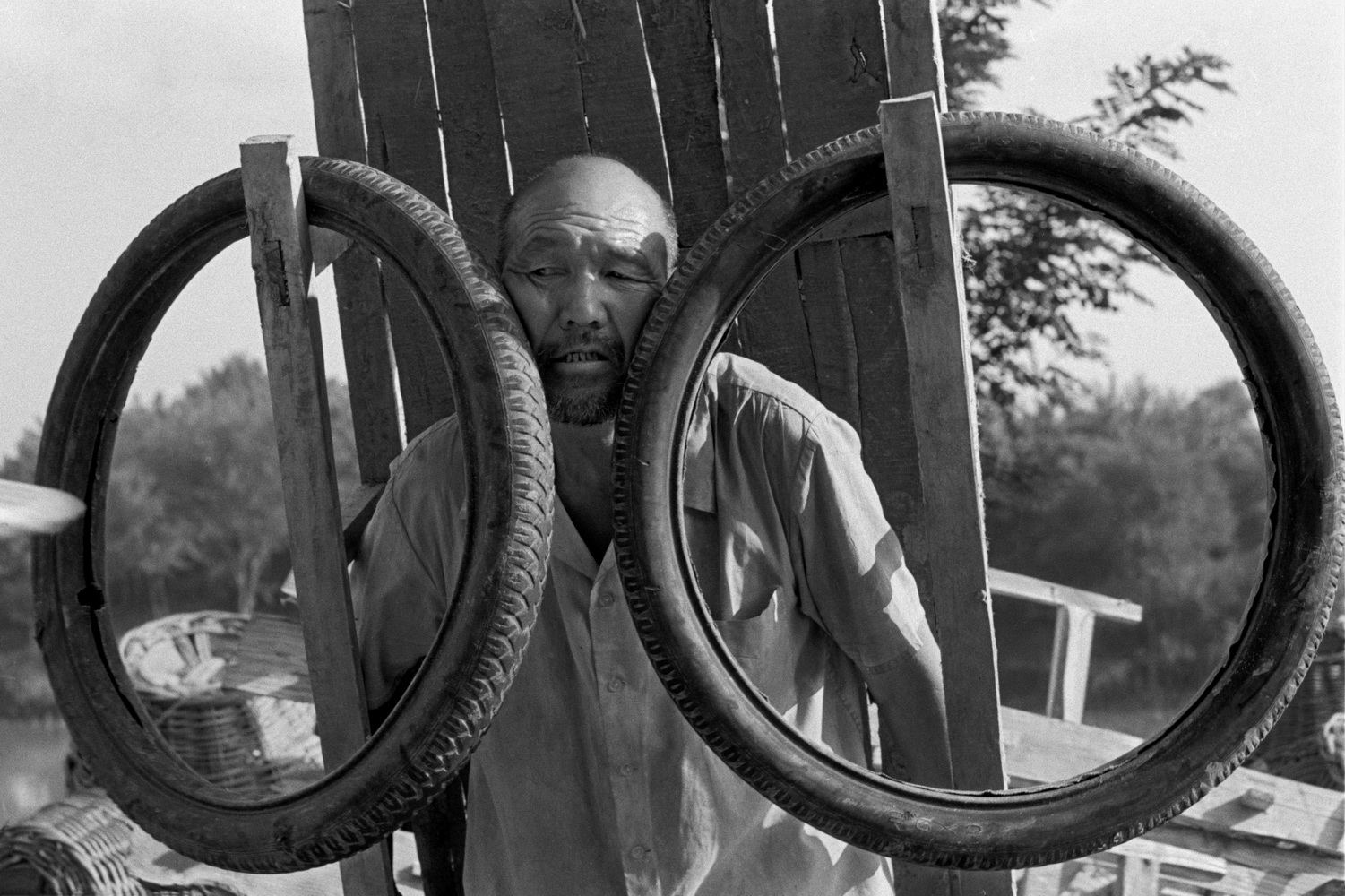

赵震海最大的付出是对个性化影像的追求,他对自己的要求非常苛刻,他坚持用个性化创造去对抗影像的流俗与平庸,宁可被探索的失败击得粉碎,也不愿被平庸拖沓得精疲力竭。他认为只有那些负载着作者更多生命信息的摄影图式,才称得上是个性化的摄影图式,而这种图式只能在现场的产生:“摄影中那些最具本质意味的东西总是当你手持相机面对对象的那一瞬间才能生发出来。当你置身某一空间,选择某一瞬间按下快门,此时,一个附载着你个人生命信息的精灵般的物质便潜藏在你的胶片之中,这一部分摄影当属你精血中涌流而出的物质,它在本质上代表着你,直通你的灵魂。”(赵震海《崎岖摄影路,蹒跚前行》)而这按下快门的一瞬间包含着对主体、陪体、神情、姿态、动态以及环境中的光、影、色、线、形等等诸种要素进行总体性的审视与把握,几乎同时,构图方式、相机位置、高度距离等等,统统都已相应确定下来,快门响过,便无法更动。他形容自己获得这些影像:艰辛备尝、历经磨难,而后,渐渐彻悟。今天我们来看赵震海20多年前拍摄的影像仍然感到厚重坚实。

赵震海是真正的把生命赋予摄影的摄影家,他对摄影的执着是深沉的、深入内心、融进灵魂的甚至有着偏执的意味,他对自己够狠,对别人也不迎合宽容,他一直默默地生活在痛苦的追求之中,真的是“性格决定命运”。近些年来赵震海的阿尔茨海默病(又称失智症)日益严重,已经失忆,只顾摄影没有把生活安排好或者根本就不会安排生活的他,在多年前辞职后至今没有医保、社保,没有收入,虽有妻子精心照料但生活陷入严重困境。2014年河南省摄影家协会主席于德水倡导,河南全视画廊运作,举办赵震海作品义卖,筹款20万元,为赵震海缓解燃眉之急。

失忆的赵震海再不能有新作问世,但他的影响依在。这种影响即来自他的影像,也来自他的精神。2003年,赵震海以第三人称写下了一份内心独白——《崎岖摄影路,蹒跚前行》,读来让人动容。摘录如下:

隔一段日子,你便一张接一张地撕碎自己的照片,你用这种办法弃旧图新。当然,你清楚这些照片是花了怎样的心血与漫长的时光才换取得来!可你一点也不吝惜;

深层意识中,你有一种不应有的影像奢侈及一种纯粹性与极端化影像占有欲!为此你用一个接着一个努力、一年接着一年的刻苦钻研与拍摄行动,义无反顾地向着那个缥缈的目标逼近。你担心,这样的影像奢侈会将自己逼向摄影的深渊;

你整夜整夜失眠,——为了摄影,头发日渐变白、稀疏。白天想摄影事多,夜间做摄影梦多,一类关于构图:朦胧中,你终于找到了一种新颖且独到的构图方式,便忘情地拍摄、拍摄,直到激动地醒来——又是南柯一梦!于是,无法言喻的失落感顿时将你团团围困,大睁两眼胡思乱想到天亮;

追求,默默地、持续不断地追求,尽管更多的是痛苦,然而,你欲罢不能。你坚持用个性化创造去对抗影像的流俗与平庸,宁可被探索的失败击得粉碎,也不愿被平庸拖沓得精疲力竭。

93年,大年初一凌晨,鞭炮齐鸣,万家团圆,其乐融融。旷野间,春寒料峭。一个藐小的身躯形单影只在山道上慢慢地攀爬着。不用猜,那一定是你!几乎所有的春节你都是这样度过;

你一步步孤独而寂寞地走去,距离所谓的主流摄影越来越远,但你无怨无悔,因为你已看清了摄坛这热闹场所,不过是生旦净末丑们亮相打闹的所在,离它远一些,离摄影便有可能近一些;

旷野间,一个孱弱的身影踽踽独行,那还是你吗?

Central China plain, the birthplace of an agricultural civilization, this is where a typical group of peasants grow and multiply.

Time flies by. The old generation of traditional Chinese farmers is dying off, photographers hope to restore the images and thus restore a period of Chinese history.

No doubt that what we’ve seen is the last generation of the classic Chinese peasants. Among them, it may include our parents or grandparents. I have no reason to move my camera and lens away from them. In face, when I turn my lens towards their face, their body; however, the image in my camera becomes so weak and incomplete. The happiness and pain that I intend to build with my visual languages, they suddenly become permanently veiled, and exists a distance between them and my camera. Some kinds of formalization and performization make me fall into the trap. I have to remind myself to get close to the subjects and be more frank in my photos. When holding the camera in my hand, facing people and other subjects, the more I become relaxed, free, and spontaneous, the more I could explore beneath the surface of subjects. It seems to be back to the origin and restart again; eventually, you can reach the inner spirit of every subject or every picture just with a calm and simple mind.

The organization and construction of personalized photographic languages concerns the success or failure of visual text. Only those image schemas that contain more information about the photographer can be considered as a personalized photograph schema. A morning of the lunar New Year’s Day, I was standing on the peak of a mountain and holding my camera, there’s a strong man climbed on the mountain and into my scene, he stood out like a man walking from the distant past. I had a feeling of the vicissitudes of history. However, everything came naturally and just so right. ‘Repetition’ and ‘variation’, ‘Harmony’ and ‘comparison,’ they both are paradox and compatible. Original status, current surroundings, and directly facing the camera—these are what the image scheme I have. No adventure, no mystery, no modification, removes the story, remove the plot, only depict the pair of eyes, he/she faces you, you face him/her, with silence, give a heart-to-heart spiritual communication. It is just a public presence of the true rural countryside life and the people themselves.

I stress the sense of confronting between a camera and its subject, the moment it records, completely determined by the performance of a tool of a camera. Oddly, many painters and masters once despised the power of photography. When will people never misunderstand photography?

It is a memory of history. It mixed with a bit of yearning and a bit of sadness. In any case, if my photos can be taken as a body text to memorize a piece of history, I’ll be content.

Persisting in the Pain

In the 1980s, Chinese photography was trying to escape from ideologization and to enter the aestheticism, Zhao Zhenhai stood out among numerous photographers with his own talent and diligence. In 1985, his "Golden Years" was selected for the third International Photography Art Exhibition in China; in 1986, his “Pearl Mountain" won the third prize of the First National Exhibition of Black-and-White Art; in 1988," his “Respective Fun" won the bronze medal prize in Chinese Rural Photography Competition Award. At the peak of his career, Zhao Zhenhai suddenly turned into a new field of documentary photography in China. In the late 80s and early 90 s, which is so far considered as the most active and fruitful time period for China; include China’s reforming and opening-up policy, the rise of various ideological trends of social and literature as well as art, and the introduction of foreign photography, etc. All these activities provided the development of Chinese photography a rich ideological resource and a strong mental dynamics. A number of photographers at the period was experiencing a difficult transformation from aestheticism to documentary photography in their own reflection and exploration process, which later in turn led to a documentary photography boom in the 90s. Zhao Zhenhai is an outstanding example. In 1992, while Zhao Zhenhai completed his documentary photography project “Coal Collectors on the Gangue Mountain” and wrote: “ten years ago, I was unscrupulous and eager to take some sweet photos to win awards, or make money, thus ignored them (documentary photographs) naturally.” Zhao is an outstanding photographer among many who have a spirit of self-reflection and recognition.

Zhao Zhenhai turns his lens towards rural areas and peasants as he was born in a peasant family. One reason is, he said, that he has a plenty of reasons to turn his camera to the theme, as his parents both are peasants. Another reason is historical awareness. He wrote in his article, Restoring The Real Survival Condition Of Chinese Peasants, “The old generation of traditional Chinese farmers is dying off, photographers hope to restore the images and thus restore a period of Chinese history.” In 1996, his first portfolio book published and soon became a precious visual Chinese modern history archive. Zhao Zhenha understood the group of people he was facing is with the largest population, but the poor living condition, and understood that the camera may cause harm for their normal life. Those coal collecting workers in the gangue mountain all are nearby township farmers, he put them as his family members and embraced a cavity affection to photograph them. He always believes that family beyond sympathy, compassion is not enough, also with a commanding composition, and should be a kind of pure identity or equivalent. This is the spiritual achievement of Chinese documentary photography humanitarianism since 1990s. Photographers assumed an equal position to approach their comparatively weak positioned subjects, and thus inspired a kind of human feeling. He said, “As a normal photographer, I always think about what my photographs would bring to the society? Those who live in remote mountainous areas, or school-deprived children, would my documentary photos help them return to school? Every time I think these questions, I regretted to choose taking photos as my career. Because when we see their real living condition, I have to admit that at the certain moment photography can help them with nothing for sure. But I will continue doing this and make an effort to depict them.

Zhao Zhenhai pursues personalized image, and very demanding on himself. He insists on the conception of a personalized image against mediocrity, think that only those photography which are carrying more care of life can be truly great. This schema needs to be brought on in the certain scene. He said, “the most essential thing about photography always happens in one second. When you press the shutter, a fairy carrying a great deal of your personal information was hidden in your file, it represents in essence, and directly to your soul.” At the same time, you overall handle the subject, facial expression, posture, dynamic, and the environment light and shade, color, line, shape, and other assorted factors. Every aspect of composition, camera position, height and so on, all should be corresponding date, and unable to change.

As a photographer, Zhao Zhenhai devotes his life to the career of photography. His love and persistence for photography is deep down into the mortal, sometimes even a little paranoid. In recent years, Zhao Zhenhai had Alzheimer's disease which turning more and more severe. He has lost his memory, and became only care about his photography, but not his body and wellness. Since he has quit many years ago, he had no Social Security and Medicare, no income, despite his wife were taking charge of everything but life inevitably run into serious trouble. Yu Deshui, the chairman of Photographer Association of Henan Province, advocated a fund-raising sale event of Zhao Zhenhai’s photographic work, which operated by the Pan-View Gallery in Luoyang. The event raised totaling 200,000 Chinese dollars and solved the pressing need for Zhao Zhenhai and his family.

Zhao Zhenhai can be no longer able to produce a new photographic book, but his spirit and influence are continued. In 2003, Zhao wrote a monologue, on a third person perspective – A Rugged Path of Photography, Stumble Forward.

1949年生于河南长垣县。

1968年——1976年在解放军某部从事文艺工作。

1973年——1978年在某县委宣传部从事摄影工作。

1980年——1995年在某市文化馆从事摄影创作。

1986年加入中国摄影家协会。

1987年毕业于沈阳鲁迅美术学院艺术摄影系。

1995年——2000年在《大河报》人摄影记者及图片编辑。

获奖:

1989年《各有情趣》获文化部全国摄影铜杯奖。

1985年《珠撒山林》获中国首届黑白摄影艺术展览铜杯奖。

1984年《钢筋铁骨》、《够有情趣》同获《中国摄影》杂志年赛三等奖。

1983年《好孙女》获《中国摄影》杂志年赛二等奖,并载入《中国摄影年鉴》。

展览:

2004年9月平遥国际大展展出《父母》系列黑白摄影作品34幅。

2004年6月16日在升达大学举办赵震海、汉斯·汤姆摄影联展,作品共60张

2003年8月广州美术馆摄影收藏展入选作品《如厕问题》、《过河收割》、《养蚕人》等3幅。

1996年5月北京“北斗星”画廊举办赵震海个展《矸石山上的捡煤人》作品25幅。

1993年《矸石山上的捡煤人》作品8幅,其中6幅作品同时在法国摄影节上展出。

1985年《金色年华》入选第三届国际影展并刊登在1985年3期《中国摄影》杂志上。

出版:

2005年北京紫图图书出版公司出版《中原密洞》图片及相关文字共10个页码。

2005年《人民摄影报》刊出《中原父老》8张,文约600字。

2003年《摄影之友》3期创作版刊出独幅照片《盲人行》。

2002年5月《视觉21》杂志刊发自行车摄影作品4幅。

2001年10月5日《中国摄影报》作品版刊出《都市》摄影作品5幅。

2001年6月《视觉21》杂志刊发组照《狂城乱马》18幅,文千字。

2001年5月15日《人民摄影报》1版刊发封面独幅大照片《黄河从门前流过》

2001年4月《视觉21杂志》刊发摄影作品11张,文700字(视觉中国栏)。

2001年4月20日《人民摄影报》作品版刊发《行走》作品6幅文300字

2001年4月11日《人民摄影报》作品博览版刊发摄影作品4幅。

2001年2月7日《人民摄影报》作品博览版刊发《都市人》作品6幅,文字300字。

2001年元月23日《中国摄影报》刊发论文《人体写真写什么》约3000字。

2001年元月19日《中国摄影报》8版整版刊发《道口》作品9幅及相关文字。

1996年《大众摄影》杂志8期刊发《影中人》摄影作品二幅

1996年《中国摄影》杂志第四期刊发赵震海《中原一代传统农民》作品集评价文字。

1996年8月浙江摄影出版社出版赵震海《中原一代传统农民》摄影专辑。

1994年《中国摄影》杂志刊出《山里的会》展览作品8幅,文2500字。

1994年《中国摄影》从第2期开始刊出文论《真诚·朴素·自由》连载9期约2500字。

1994年3月11日《人民摄影报》封面刊出独幅作品《盲人行》。

1993年台湾第10期《摄影家》杂志“中国摄影专辑”刊发《矸石山上的捡煤人》作品8幅,文2500字,其中6幅作品同时在法国摄影节上展出。

1989年《中国摄影家》杂志第五期刊发摄影作品3幅。

1985年《中国摄影》杂志第四期“我的艺术追求”栏目刊发《戏迷》等4幅作品及短文。

Zhao Zhenhai

1949 born in Changhuan, Henan.

Served at The people's liberation army

Served as photographer at a County Committee propaganda department.

Served in photographic creation at city municipal cultural center

Joined China’s Photographer’s Association

Graduated from Shenyang Luxun academy of fine arts, department of photography.

Served as photographer and photo editor at the River Newspaper

Awards

The third prize of The ministry of culture national photography

The third prize of China's first black and white photography art exhibition

The third prize of China Photography magazine competition

The second prize of China Photography magazine competition

Exhibitions

2004 “parents” black and white series, Pingyao international Photography Festival

2004 Photography Exhibition of Zhao Zhenhai And Hans Tom, Shengda University

2003 “toilet problem”, “crossing the river by harvest”, “sericulture people” , Guangzhou museum of art

1996 “pick up coal gangue mountain people”, Zhao Zhenhai Solo Exhibition, Beijing “dipper” galleries

1993 “The man picking up coal on gangue mountain”, photography festival, France

1985 “Golden years”, the third China international film festival

Publications

2005 “The Central Plain Secrete Cave”, Beijing purple picture book publishing company

2005 “the central plain folk people”, People's photography newspaper

2003 “ Walking with the blind”, Friends of Photography Magazine

2002 “Bicycles”, Vision 21 Magazine

2001 “Urban cities”, China Photography Newspaper

2001 “Crazy City”, Vision 21 Magazine

2001 “The Yellow River running cross the door ”People’s Photography Newspaper

2001 “walking” People’s Photography Newspaper

2001 “Urban People”, People’s Photography Newspaper

2001 Article “What is nude portraits?”, China Photography Newspaper

2001 “the street cross”, China Photography Newspaper

1996 “A generation of traditional Central China farmers ”, China Photography Journal

1996 “A generation of traditional Central China farmers ”, Zhejiang photography publishing

1994 “Meeting in a village”, China Photography Journal

1994 “sincere, simple, and Freedom “, China Photography Journal

1985 “Opera Fans” ,China Photography Journal

还农民以生存本相

赵震海

中国,漫长的农耕历史,农民的汪洋大海。

中原,农耕文化的发祥地,这里繁衍生息着的是一群最具代表性的农民。

时光荏苒。降生在旧中国的那一代传统农民正一个个相继离去,尽快用相机留住他们,留住他们便是凝固了一段历史。

毫无疑问这是我们所能看到的最后一代古典式农民。历史在他们身上投下浓浓的影子,他们的双肩承载着更多的民族重荷。我们有理由将他们看作一种流动的文化符号,一个个连缀起来,有可能成为一本动感的断代史。

这群农民中有我的父母和父母的父母。我没有理由不将镜头对准他们。可当我真的将镜头对准他们,又觉得与他们相比,镜头前的画面竟是那样的乏力、缺憾。我曾一味营造对于他们来说尚属冥想和虚幻中的幸福,亦曾竭力渲染他们那几经努力尚挥之不去的悲苦,然镜头与他们之间似有一种隔膜,一些表现化、形式化的东西诱使我误入陷阱。我提醒自己,应更加走近一些,更加直率一些。当手举相机,面对对象,更轻松、更自如、更即兴地揿动快门,便有可能穿透表象而直达底里。诀别一切现有成语,回到零点重新起步,最终,只求得一个平朴与自然,从而有可能一步跨近人的心灵。

个性化摄影语言的罗织和构建直接关系着文本的成败。只有那些负载着作者更多生命信息的摄影图式,才称得上是个性化的摄影图式。一切恰如其分的摄影图式都只能是当手举起相机面对对象的那一瞬所产生。闭门造车的摄影只能是远离摄影本质的边缘摄影。那年大年初一早上,当我在一山顶手举相机,框定半山坡爬上来的一个汉子时,淡远的山峦作陪衬,人物似有从遥远的时光隧道中走来的历史沧桑感。我眼睛蓦然一亮:也许一种恰切的图式找到了。我按捺激情待其比例在取景器中恰切时摁下快门---远山,正面半身,横幅构图。从此,这个图式被固定下来拍男人。拍妇女和老太则找到了另一图式:全身,横幅,院落家庭作背景,与其身份及性格相吻合。重复——变化、和谐——对比,这是悖谬同时兼容的两对。原始状态,现场环境,正面直视镜头,这便是属于我的图式的全部。不求惊心动魄,不求角度奇谲,也不加任何修饰,剔除故事,删去情节,只刻意描绘一双眼睛,他面对着你,你面对着他,默默无语,纯然一种两心相映式的灵魂沟通。毋需渲染,毋需说教,仅仅是山民农人原始情状的群体亮相,还了他们一个原色的本真罢了。

我只是强调了照相机与对象之间的一种直面感,这一瞬间所生发出的特有魅力极尽微妙,完全由照相机这种特殊的工具性能所决定,其他媒体无法替代。令人费解的是,昔日艺术大师曾鄙薄过它。而今的世人忽视了它,何时人们不再误解摄影?

不必拘泥于任何主义,只需克服那种好——坏、善——恶的两极化对位模式,躲避超凡脱俗的辉煌,恢复大量被滤除掉的中间色调,由对单个人的典型性的追求,转向对民族群体生存本相的思考。

这是一个悠远的历史记忆。这记忆中不免有几许怀恋、几多哀婉的情调,少不得还夹带些许隐隐的惆怅和无奈。但无论如何,如能权且将其作为一可资追怀的历史文本,则我心足矣。

中原,农耕文化的发祥地,这里繁衍生息着的是一群最具代表性的农民。

时光荏苒。降生在旧中国的那一代传统农民正一个个相继离去,尽快用相机留住他们,留住他们便是凝固了一段历史。

毫无疑问这是我们所能看到的最后一代古典式农民。历史在他们身上投下浓浓的影子,他们的双肩承载着更多的民族重荷。我们有理由将他们看作一种流动的文化符号,一个个连缀起来,有可能成为一本动感的断代史。

这群农民中有我的父母和父母的父母。我没有理由不将镜头对准他们。可当我真的将镜头对准他们,又觉得与他们相比,镜头前的画面竟是那样的乏力、缺憾。我曾一味营造对于他们来说尚属冥想和虚幻中的幸福,亦曾竭力渲染他们那几经努力尚挥之不去的悲苦,然镜头与他们之间似有一种隔膜,一些表现化、形式化的东西诱使我误入陷阱。我提醒自己,应更加走近一些,更加直率一些。当手举相机,面对对象,更轻松、更自如、更即兴地揿动快门,便有可能穿透表象而直达底里。诀别一切现有成语,回到零点重新起步,最终,只求得一个平朴与自然,从而有可能一步跨近人的心灵。

个性化摄影语言的罗织和构建直接关系着文本的成败。只有那些负载着作者更多生命信息的摄影图式,才称得上是个性化的摄影图式。一切恰如其分的摄影图式都只能是当手举起相机面对对象的那一瞬所产生。闭门造车的摄影只能是远离摄影本质的边缘摄影。那年大年初一早上,当我在一山顶手举相机,框定半山坡爬上来的一个汉子时,淡远的山峦作陪衬,人物似有从遥远的时光隧道中走来的历史沧桑感。我眼睛蓦然一亮:也许一种恰切的图式找到了。我按捺激情待其比例在取景器中恰切时摁下快门---远山,正面半身,横幅构图。从此,这个图式被固定下来拍男人。拍妇女和老太则找到了另一图式:全身,横幅,院落家庭作背景,与其身份及性格相吻合。重复——变化、和谐——对比,这是悖谬同时兼容的两对。原始状态,现场环境,正面直视镜头,这便是属于我的图式的全部。不求惊心动魄,不求角度奇谲,也不加任何修饰,剔除故事,删去情节,只刻意描绘一双眼睛,他面对着你,你面对着他,默默无语,纯然一种两心相映式的灵魂沟通。毋需渲染,毋需说教,仅仅是山民农人原始情状的群体亮相,还了他们一个原色的本真罢了。

我只是强调了照相机与对象之间的一种直面感,这一瞬间所生发出的特有魅力极尽微妙,完全由照相机这种特殊的工具性能所决定,其他媒体无法替代。令人费解的是,昔日艺术大师曾鄙薄过它。而今的世人忽视了它,何时人们不再误解摄影?

不必拘泥于任何主义,只需克服那种好——坏、善——恶的两极化对位模式,躲避超凡脱俗的辉煌,恢复大量被滤除掉的中间色调,由对单个人的典型性的追求,转向对民族群体生存本相的思考。

这是一个悠远的历史记忆。这记忆中不免有几许怀恋、几多哀婉的情调,少不得还夹带些许隐隐的惆怅和无奈。但无论如何,如能权且将其作为一可资追怀的历史文本,则我心足矣。

痛苦中的执着

陈晓琦

上世纪80年代,力图走出意识形态化的中国摄影又步入了唯美主义的风潮,赵震海凭着自己的灵性和勤奋脱颖而出,1985年《金色年华》入选第三届国际摄影艺术展览,1986年《珠撒山林》获首届全国黑白艺术作品展览三等奖,1988年《各有情趣》获中国农村摄影大赛铜牌奖……。正在似乎前途无限的时候赵震海在唯美的道路上突然刹车,转向了表现普通百姓生活的纪实摄影。80年代后期和90年代初,是一个至今让人怀念的思想最为活跃且富有成果的时期,改革开放、拨乱反正、各种社会思潮文艺思潮的兴起、国外摄影的引进为中国摄影的变革发展提供了丰富的思想资源和强大的精神动力,许多摄影家在反思和探索中做着从唯美走向纪实的艰难的转向,实际上发起了90年代至世纪末的纪实摄影的热潮,赵震海是能得风气之先、转变迅速而果断的一个。1992年,赵震海完成了他的纪实摄影专题《矸石山上捡煤人》。这是他十年前就发现的场景,当时却没有拍摄。他写道:“十年前我利欲熏心,急于拍些甜美的东西好去获奖,给自己捞取好处,自然冷落了他们。”(赵震海《我拍矸石山上采煤人》)那一批在反思中寻求转变的摄影家都是具有自我反省精神的人。赵震海主要把镜头对准了农村农民,他的思想来源其一是血缘情感,他说我的父母和父母的父母都是农民,我没有理由不将镜头对准他们;其二是历史意识:“降生在旧中国的那一代传统农民正在一个个相继离去,尽快用相机留住他们,留住他们便是留住了一段历史。”(赵震海《还农民以生存本相》)1996年他的第一部作品集《中原·一代传统农民》问世,这部农村影像成为珍贵的历史文献。赵震海非常明白他面对的是中国最大的当时还非常贫穷的弱势群体,也非常明白照相机天生的侵略性自己的拍摄是一种对他们的掠夺,赵震海极力地小心翼翼地避免对他们的伤害。生活非常艰苦劳累的矸石山捡煤人都是附近县乡的农民,他把他们看做自己的父兄姐弟,对他们抱着一腔亲情,他认为亲情超越了同情,同情不够,还带有居高临下的成分,应该是一种纯粹的认同或等同。这种认识是上世纪90年代初中国纪实摄影人道主义的精神成果。摄影家以平等、认同的姿态对待相对弱势的拍摄对象表现出一种人文情怀,并且获得心理的平衡:“由于有了位置上的平等关系,我虽从他们那里取走了自己所要的东西——照片,但也决不再是非道德的掠夺。”(赵震海《我拍矸石山上采煤人》)但是赵震海并没有因此心安理得,一种精神上的无奈和痛苦一直伴随着他的纪实摄影,因为虽然“道德地”从他们身上取走了照片,但是照片对改变他们生活的困难毫无帮助:“作为一个普通拍摄者,我常常思考,自己的影像能给社会带来些什么?那些偏远山乡的缺衣少食者,还有那里的失学儿童们,你的影像能让他们重返学堂吗?还有那些缺医少药者,你能医治他们的病痛吗?想到这些便生出‘选择摄影也许是个错误’这样的念头,因为我们眼见着不少人缺衣少食,儿童为此辍学,可是,无助的摄影对此却一筹莫展。于是,我不再像昔日那样对摄影梦萦魂牵,因为他太懦弱,太无用!”(赵震海《为农民造像》)摄影使他看到了更多的贫穷苦难,却无助于他悲天悯人的情怀,激愤的言辞透出内心的痛苦。有多少摄影家像赵震海一样承受着这样的痛苦?

赵震海最大的付出是对个性化影像的追求,他对自己的要求非常苛刻,他坚持用个性化创造去对抗影像的流俗与平庸,宁可被探索的失败击得粉碎,也不愿被平庸拖沓得精疲力竭。他认为只有那些负载着作者更多生命信息的摄影图式,才称得上是个性化的摄影图式,而这种图式只能在现场的产生:“摄影中那些最具本质意味的东西总是当你手持相机面对对象的那一瞬间才能生发出来。当你置身某一空间,选择某一瞬间按下快门,此时,一个附载着你个人生命信息的精灵般的物质便潜藏在你的胶片之中,这一部分摄影当属你精血中涌流而出的物质,它在本质上代表着你,直通你的灵魂。”(赵震海《崎岖摄影路,蹒跚前行》)而这按下快门的一瞬间包含着对主体、陪体、神情、姿态、动态以及环境中的光、影、色、线、形等等诸种要素进行总体性的审视与把握,几乎同时,构图方式、相机位置、高度距离等等,统统都已相应确定下来,快门响过,便无法更动。他形容自己获得这些影像:艰辛备尝、历经磨难,而后,渐渐彻悟。今天我们来看赵震海20多年前拍摄的影像仍然感到厚重坚实。

赵震海是真正的把生命赋予摄影的摄影家,他对摄影的执着是深沉的、深入内心、融进灵魂的甚至有着偏执的意味,他对自己够狠,对别人也不迎合宽容,他一直默默地生活在痛苦的追求之中,真的是“性格决定命运”。近些年来赵震海的阿尔茨海默病(又称失智症)日益严重,已经失忆,只顾摄影没有把生活安排好或者根本就不会安排生活的他,在多年前辞职后至今没有医保、社保,没有收入,虽有妻子精心照料但生活陷入严重困境。2014年河南省摄影家协会主席于德水倡导,河南全视画廊运作,举办赵震海作品义卖,筹款20万元,为赵震海缓解燃眉之急。

失忆的赵震海再不能有新作问世,但他的影响依在。这种影响即来自他的影像,也来自他的精神。2003年,赵震海以第三人称写下了一份内心独白——《崎岖摄影路,蹒跚前行》,读来让人动容。摘录如下:

隔一段日子,你便一张接一张地撕碎自己的照片,你用这种办法弃旧图新。当然,你清楚这些照片是花了怎样的心血与漫长的时光才换取得来!可你一点也不吝惜;

深层意识中,你有一种不应有的影像奢侈及一种纯粹性与极端化影像占有欲!为此你用一个接着一个努力、一年接着一年的刻苦钻研与拍摄行动,义无反顾地向着那个缥缈的目标逼近。你担心,这样的影像奢侈会将自己逼向摄影的深渊;

你整夜整夜失眠,——为了摄影,头发日渐变白、稀疏。白天想摄影事多,夜间做摄影梦多,一类关于构图:朦胧中,你终于找到了一种新颖且独到的构图方式,便忘情地拍摄、拍摄,直到激动地醒来——又是南柯一梦!于是,无法言喻的失落感顿时将你团团围困,大睁两眼胡思乱想到天亮;

追求,默默地、持续不断地追求,尽管更多的是痛苦,然而,你欲罢不能。你坚持用个性化创造去对抗影像的流俗与平庸,宁可被探索的失败击得粉碎,也不愿被平庸拖沓得精疲力竭。

93年,大年初一凌晨,鞭炮齐鸣,万家团圆,其乐融融。旷野间,春寒料峭。一个藐小的身躯形单影只在山道上慢慢地攀爬着。不用猜,那一定是你!几乎所有的春节你都是这样度过;

你一步步孤独而寂寞地走去,距离所谓的主流摄影越来越远,但你无怨无悔,因为你已看清了摄坛这热闹场所,不过是生旦净末丑们亮相打闹的所在,离它远一些,离摄影便有可能近一些;

旷野间,一个孱弱的身影踽踽独行,那还是你吗?

Restoring the Real Survival Condition of Chinese Peasants

Zhao Zhen

China has a long agricultural history, and an ocean-like big population of peasants.Central China plain, the birthplace of an agricultural civilization, this is where a typical group of peasants grow and multiply.

Time flies by. The old generation of traditional Chinese farmers is dying off, photographers hope to restore the images and thus restore a period of Chinese history.

No doubt that what we’ve seen is the last generation of the classic Chinese peasants. Among them, it may include our parents or grandparents. I have no reason to move my camera and lens away from them. In face, when I turn my lens towards their face, their body; however, the image in my camera becomes so weak and incomplete. The happiness and pain that I intend to build with my visual languages, they suddenly become permanently veiled, and exists a distance between them and my camera. Some kinds of formalization and performization make me fall into the trap. I have to remind myself to get close to the subjects and be more frank in my photos. When holding the camera in my hand, facing people and other subjects, the more I become relaxed, free, and spontaneous, the more I could explore beneath the surface of subjects. It seems to be back to the origin and restart again; eventually, you can reach the inner spirit of every subject or every picture just with a calm and simple mind.

The organization and construction of personalized photographic languages concerns the success or failure of visual text. Only those image schemas that contain more information about the photographer can be considered as a personalized photograph schema. A morning of the lunar New Year’s Day, I was standing on the peak of a mountain and holding my camera, there’s a strong man climbed on the mountain and into my scene, he stood out like a man walking from the distant past. I had a feeling of the vicissitudes of history. However, everything came naturally and just so right. ‘Repetition’ and ‘variation’, ‘Harmony’ and ‘comparison,’ they both are paradox and compatible. Original status, current surroundings, and directly facing the camera—these are what the image scheme I have. No adventure, no mystery, no modification, removes the story, remove the plot, only depict the pair of eyes, he/she faces you, you face him/her, with silence, give a heart-to-heart spiritual communication. It is just a public presence of the true rural countryside life and the people themselves.

I stress the sense of confronting between a camera and its subject, the moment it records, completely determined by the performance of a tool of a camera. Oddly, many painters and masters once despised the power of photography. When will people never misunderstand photography?

It is a memory of history. It mixed with a bit of yearning and a bit of sadness. In any case, if my photos can be taken as a body text to memorize a piece of history, I’ll be content.

Persisting in the Pain

Chen Xiaoqi

In the 1980s, Chinese photography was trying to escape from ideologization and to enter the aestheticism, Zhao Zhenhai stood out among numerous photographers with his own talent and diligence. In 1985, his "Golden Years" was selected for the third International Photography Art Exhibition in China; in 1986, his “Pearl Mountain" won the third prize of the First National Exhibition of Black-and-White Art; in 1988," his “Respective Fun" won the bronze medal prize in Chinese Rural Photography Competition Award. At the peak of his career, Zhao Zhenhai suddenly turned into a new field of documentary photography in China. In the late 80s and early 90 s, which is so far considered as the most active and fruitful time period for China; include China’s reforming and opening-up policy, the rise of various ideological trends of social and literature as well as art, and the introduction of foreign photography, etc. All these activities provided the development of Chinese photography a rich ideological resource and a strong mental dynamics. A number of photographers at the period was experiencing a difficult transformation from aestheticism to documentary photography in their own reflection and exploration process, which later in turn led to a documentary photography boom in the 90s. Zhao Zhenhai is an outstanding example. In 1992, while Zhao Zhenhai completed his documentary photography project “Coal Collectors on the Gangue Mountain” and wrote: “ten years ago, I was unscrupulous and eager to take some sweet photos to win awards, or make money, thus ignored them (documentary photographs) naturally.” Zhao is an outstanding photographer among many who have a spirit of self-reflection and recognition.

Zhao Zhenhai turns his lens towards rural areas and peasants as he was born in a peasant family. One reason is, he said, that he has a plenty of reasons to turn his camera to the theme, as his parents both are peasants. Another reason is historical awareness. He wrote in his article, Restoring The Real Survival Condition Of Chinese Peasants, “The old generation of traditional Chinese farmers is dying off, photographers hope to restore the images and thus restore a period of Chinese history.” In 1996, his first portfolio book published and soon became a precious visual Chinese modern history archive. Zhao Zhenha understood the group of people he was facing is with the largest population, but the poor living condition, and understood that the camera may cause harm for their normal life. Those coal collecting workers in the gangue mountain all are nearby township farmers, he put them as his family members and embraced a cavity affection to photograph them. He always believes that family beyond sympathy, compassion is not enough, also with a commanding composition, and should be a kind of pure identity or equivalent. This is the spiritual achievement of Chinese documentary photography humanitarianism since 1990s. Photographers assumed an equal position to approach their comparatively weak positioned subjects, and thus inspired a kind of human feeling. He said, “As a normal photographer, I always think about what my photographs would bring to the society? Those who live in remote mountainous areas, or school-deprived children, would my documentary photos help them return to school? Every time I think these questions, I regretted to choose taking photos as my career. Because when we see their real living condition, I have to admit that at the certain moment photography can help them with nothing for sure. But I will continue doing this and make an effort to depict them.

Zhao Zhenhai pursues personalized image, and very demanding on himself. He insists on the conception of a personalized image against mediocrity, think that only those photography which are carrying more care of life can be truly great. This schema needs to be brought on in the certain scene. He said, “the most essential thing about photography always happens in one second. When you press the shutter, a fairy carrying a great deal of your personal information was hidden in your file, it represents in essence, and directly to your soul.” At the same time, you overall handle the subject, facial expression, posture, dynamic, and the environment light and shade, color, line, shape, and other assorted factors. Every aspect of composition, camera position, height and so on, all should be corresponding date, and unable to change.

As a photographer, Zhao Zhenhai devotes his life to the career of photography. His love and persistence for photography is deep down into the mortal, sometimes even a little paranoid. In recent years, Zhao Zhenhai had Alzheimer's disease which turning more and more severe. He has lost his memory, and became only care about his photography, but not his body and wellness. Since he has quit many years ago, he had no Social Security and Medicare, no income, despite his wife were taking charge of everything but life inevitably run into serious trouble. Yu Deshui, the chairman of Photographer Association of Henan Province, advocated a fund-raising sale event of Zhao Zhenhai’s photographic work, which operated by the Pan-View Gallery in Luoyang. The event raised totaling 200,000 Chinese dollars and solved the pressing need for Zhao Zhenhai and his family.

Zhao Zhenhai can be no longer able to produce a new photographic book, but his spirit and influence are continued. In 2003, Zhao wrote a monologue, on a third person perspective – A Rugged Path of Photography, Stumble Forward.

豫公网安备 41019602002106号

豫公网安备 41019602002106号